“Come along, darlings, it’s time for dinner.”

To human ears the remark would have sounded like “Chirp-chirp,” but the ten children of Mrs. Theodosia Quail immediately awoke from their afternoon nap on this autumn day and scurried after her.

“Bob-WHITE, Bob-WHITE,” Theodosia’s husband, Aloysius Quail, called. By this he meant, “After dinner, we’re joining a covey and making for that thicket of huisache over there. That’s where we’ll spend the night.”

All ten chicks cheeped assent and followed Theodosia. Aloysius, always impatient, had already finished dinner and was now scouting the route to the thicket.

Overhead the South Texas sky glinted with a harsh gray light; the terrain below was as brown as the quail foraging on it for weed seeds, roots, and anything else they could find.

“Eat your insects, children,” Theodosia reminded her chicks. “They’ll make you grow up big and strong.”

At last everyone was ready to leave. Dust was shaken off wings, feathers were smoothed with beaks, and toes scraped clean. Theodosia, Aloysius, and the chicks joined the covey moving slowly toward the sheltering huisache. ”Don’t like the look of that sky,” Aloysius whispered to Theo as they settled themselves for the night. “Too bright.”

“You’re such a worry-wart,” Theo said. “Everything’s going to be fine. Now hush, they’re all asleep except Paprika and Parsifal.”

Two hours later Theodosia woke suddenly with a premonition of danger. In the distance she could see a party of humans and a dog approaching.

“Chirrup-chirrup,” she said. “Children, there are predators on the scene–get ready to fly!”

The hunting party of three men and a dog strode briskly through the metallic afternoon light.

“I like hunting,” Leopold Spottiswoode said. “This is the first time I’ve ever hunted quail, though. What else do you have on the ranch, Willis?”

“White-tailed deer,” Willis, the guide, said. “Wild turkey.” He looked up at the sky, frowned, then squinted at the sacahuista grassland stretching before them.

“Wild turkey,” Rufus Meany said. “Makes me think of bourbon. Some of that would go good with pan-fried quail, country gravy, and biscuits for dinner tonight.”

“What about quail in rose petal sauce?” Spottiswoode said. “That would be good too.”

“Hell, no,” Meany said, with dark memories of a film in which the ingestion of that very dish had driven people into a sexual frenzy. “Don’t hold with that fancy stuff.”

“Don’t like the look of that sky,” Willis said. “Could be a blue norther on the way.”

“Never known a blue norther to hit at the end of October,” Meany said. “Don’t be stupid.”

“You’re the one who’s stupid,” Spottiswoode said. “A blue norther can hit on the last day of October or the last day of February.”

Brutus, the English pointer, suddenly stood still and sniffed the air.

“He’s scented the quail,” Willis said. “All right, when I give Brutus the signal, the quail will fly up so you can shoot ’em. Here, boy!”

At that moment Theodosia invoked the Quail Goddess.

“Oh, Asteria, Goddess of falling stars and prophecy, of night and the realm of the dead; you, Goddess, who fled from Zeus by transforming yourself into a quail and diving into the sea to escape him; Asteria, Quail Goddess, I invoke you at Samhain, when the veil parts between the worlds. Help us escape from the hunters, Quail Goddess!”

The sky turned blue-black, the air temperature dropped thirty degrees, and rain pelted the parched earth. The quail hiding under the huisache were invisible in the unnatural darkness.

Brutus barked, Willis swore, and Meany shot Spottiswoode in the buttocks.

Accidentally, of course.

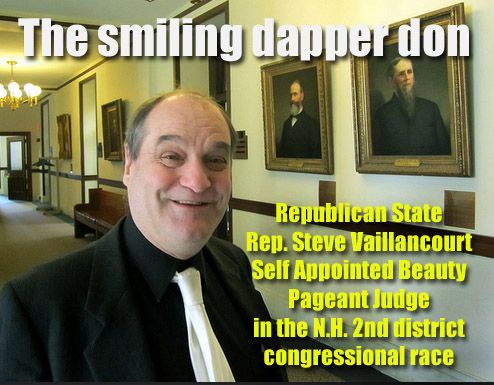

Steve Vaillancourt, a Republican state representative for New Hampshire attempts to turn the New Hampshire’s 2nd district congressional race into his own personal defacto beauty pageant wherein he acts as the self-appointed judge, wherein he pronounces in his judgement that the determining factor in the race will come down to the matter of his judgement that incumbent Democratic state Rep. Ann McLane Kuster is “as ugly as sin” and cannot win. In a continuation of his sexist remarks, he goes on to shockingly say that drag queens even look better than her and in doing so tries to create what may only be seen as a circus-like beauty pageant atmosphere to grab headlines in yet another desperate Republican bid to win ugly.

Steve Vaillancourt, a Republican state representative for New Hampshire attempts to turn the New Hampshire’s 2nd district congressional race into his own personal defacto beauty pageant wherein he acts as the self-appointed judge, wherein he pronounces in his judgement that the determining factor in the race will come down to the matter of his judgement that incumbent Democratic state Rep. Ann McLane Kuster is “as ugly as sin” and cannot win. In a continuation of his sexist remarks, he goes on to shockingly say that drag queens even look better than her and in doing so tries to create what may only be seen as a circus-like beauty pageant atmosphere to grab headlines in yet another desperate Republican bid to win ugly.

New Hampshire State Rep. Steve Vaillancourt wrote a long blog post predicting the outcome of the race in the state’s 2nd Congressional District on one factor: incumbent Democratic Rep. Ann McLane Kuster’s looks.

New Hampshire State Rep. Steve Vaillancourt wrote a long blog post predicting the outcome of the race in the state’s 2nd Congressional District on one factor: incumbent Democratic Rep. Ann McLane Kuster’s looks.