So much of our history, as black Americans, is often lost, forgotten or obscured. Key moments of that history often take us to North Carolina, where struggles are still being led by groups like Moral Mondays, spearheaded by Rev. William Barber.

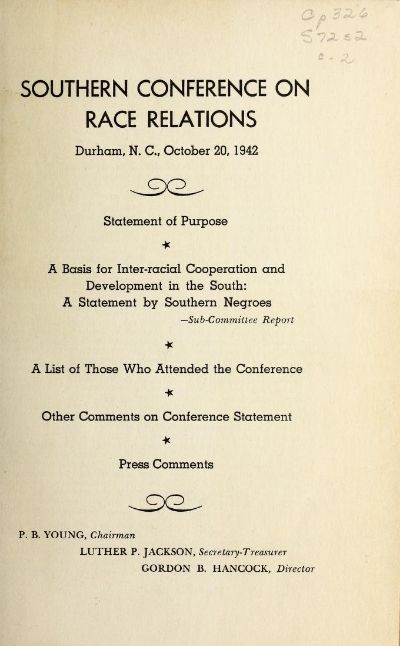

One such historical moment was the issuance of The Durham Manifesto, as a result of the October of 1942 Southern Conference on Race Relations, which was held in Durham, North Carolina.

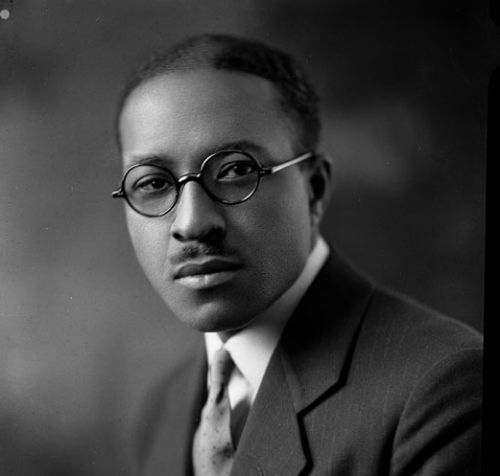

As he opened the Southern Conference on Race Relations on October 20, 1942, sociologist Gordon B. Hancock compared the meeting of fifty-seven African-American professionals to the gatherings of revolutionaries two centuries before in Boston’s Faneuil Hall. “The matter handled in Faneuil Hall was delicate, but it was firmly handled and the world thereby was blessed,” he told those assembled at the North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University) in Durham. “So in this historic meeting today, whatever advance step we may make in race relations will rebound to the advantage of the South and nation no less than to the advancement of the Negro race.”

Hancock, a 57-year-old professor at Virginia Union University in Richmond and a nationally-syndicated columnist for African-American newspapers, had joined with several other prominent African-Americans from the South in calling the Durham meeting. They were concerned about the poor state of relations between blacks and whites in the South. Lynchings were still occurring. Black unemployment was high. And, as had happened during World War I, African-American soldiers were fighting for democracy overseas while facing segregation at home. In a December 1941 column titled “Interracial Hypertension”, Hancock had cautioned that “unless matters are speedily taken in hand and shaped according to some constructive plan, we shall probably lose many important gains in race relations that have been won through many years, through sweat and tears.” In a subsequent column, Hancock called for a “Southern Charter for Race Relations.” Such a document, Hancock wrote, would “set out specific demands such as the moral right to work for an honest living; the right to share equitably in the educational opportunities, without which [African-Americans] cannot function in a democracy; the right to vote for the mayors and governors, law makers and law enforcers, officials who control [African-Americans’] daily life, as well as for the President, who is powerless in local affairs.”

The gathering included many leading black southern educators and intellectuals, mostly male, but five women attended, including education pioneer Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown.

What is changing is that sites that document history, have begun to include black history as part of the historical timeline of events, like this entry from the North Carolina Museum of History:

A committee headed by Charles S. Johnson of Fisk University issues a document that becomes known as the Durham Manifesto. It acknowledges that World War II has generated increased racial tensions. The statement demands complete voting rights for African Americans and an end to white primaries, evasions of the law, and intimidation. It insists on equal access to all jobs.

“Southern Conference on Race Relations, Durham, N.C., October 20, 1942,” is a link to the full digitized text.

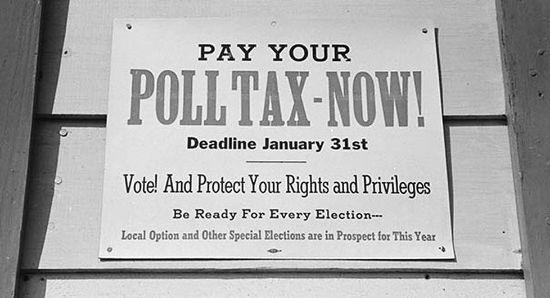

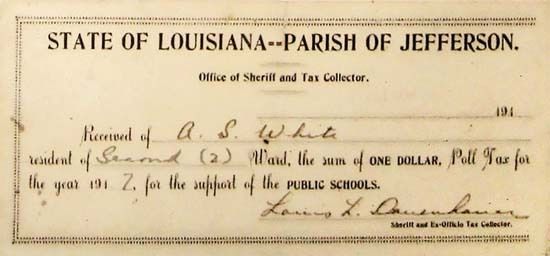

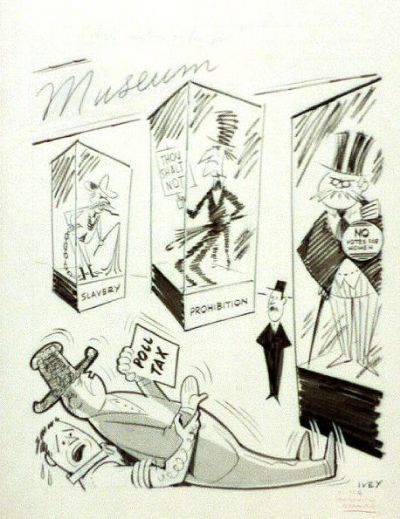

Reading this, written over 70 years ago, says a lot about how far we have come, but also makes it clear that in some areas our issues are the same, and how far we still have to go. The voter ID laws of today, are the poll taxes they reference. The abuses of police power-same shit, different day.

POLITICAL AND CIVIL RIGHTS

1. We regard the ballot as a safeguard of democracy. Any discrimination

against citizens in the exercise of the voting privilege,

on account of race or poverty, is detrimental to the freedom

of these citizens and to the integrity of the State. We therefore

record ourselves as urging now:

a. The abolition of the poll tax as a prerequisite to voting.

b. The abolition of the white primary.

c. The abolition of all forms of discriminatory practices, evasions

of the law, and intimidations of citizens seeking to exercise their

right of franchise.

2. Exclusion of Negroes from jury service because of race has

been repeatedly declared unconstitutional. This practice we believe

can and should be discontinued now.

3. a. Civil rights include personal security against abuses of

police power by white officers of the law. These abuses, which include

wanton killings, and almost routine beatings of Negroes,

whether they be guilty or innocent of an offense, should be stopped

now, not only out of regard for the safety of Negroes, but of common

respect for the dignity and fundamental purpose of the law.

b. It is the opinion of this group that the employment of Negro police

will enlist the full support of Negro citizens in control of lawless elements

of their own group.

4. In the public carriers and terminals, where segregation of the

races is currently made mandatory by law as well as by established

custom, it is the duty of Negro and white citizens to insist that

these provisions be equal in kind and quality and in character of

maintenance.

5. Although there has been, over the years, a decline in lynchings,

the practice is still current in some areas of the South, and

substantially, even if indirectly, defended by resistance to Federal

legislation designed to discourage the practice. We ask that the

States discourage this fascistic expression by effective enforcement

of present or of new laws against this crime by apprehending and

punishing parties participating in this lawlessness.

If the States are unable, or unwilling to do this, we urge the support

of all American citizens who believe in law and order in securing

Federal legislation against lynching.

Duke University history professor Ray Gavins, wrote about this history last year in Forgotten manifesto challenged white South, highlighting seven major issues addressed at the conference.

Groups then scrutinized seven issues: political and civil rights; industry and labor; service occupations; education; agriculture; armed forces; social welfare and health. When proceedings ended, Benjamin E. Mays, president of Morehouse College, recommended writing a statement “commensurate with the possibilities of the occasion.”

Accordingly, the body chose a sub-editorial committee, chaired by sociologist Charles S. Johnson of Fisk University, to write it.

The finished document judiciously stated blacks’ opposition to Jim Crow, plus their civic priorities, and challenged moderate and liberal whites to join them in pursuing equal citizenship and justice for all.

It announced: “We are fundamentally opposed to the principle and practice of compulsory segregation in our American society, whether of races or classes or creeds, however, we regard it as both sensible and timely to address … current problems of racial discrimination and neglect.”

Its key demands included the right to vote; abolition of the poll tax, white primary, harassment of voters, and police abuses; a Federal anti-lynching law; Negro jury and government representation; fair employment of Negro police officers, defense workers, and workers’ right of collective bargaining; Social Security benefits for service and farm occupations; equalization of Teachers’ salaries, school facilities, and higher education opportunities; ending the segregated U.S. Military; and publicly-funded hospitals’ inclusion of Negro patients.

“The correction of these problems is not only a moral matter,” it concluded, “but a practical necessity in winning the war and in winning the peace.”

Segregation in neighborhoods, housing and education continues. Access to affordable health care is being still being blocked. Déjà vu all over again!

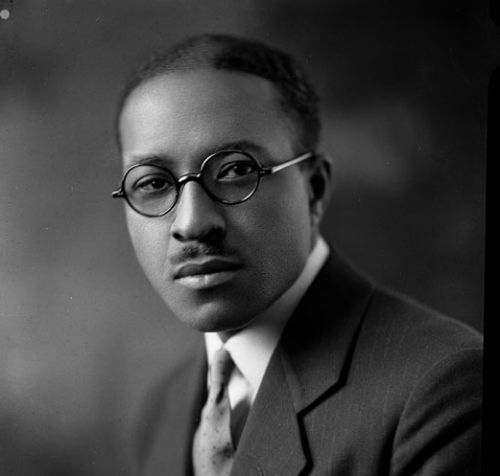

Most contemporary students of black history and sociology are familiar with names like those of W.E.B DuBois, and E. Franklin Frazier, and not with the work and history of Charles S. Johnson, who was a major voice in the black community of his time.

Charles Spurgeon Johnson, one of the leading 20th Century black sociologists, was born in Bristol, Virginia on July 24, 1893. After receiving his B.A. from Virginia Union University in Richmond, he studied sociology with the noted sociologist Robert E. Park at the University of Chicago where he earned a Ph.D. in 1917…

Surviving and being a witness to the race riots during the Red Summer of 1917, Johnson investigated the causes of the riots and produced an assessment for the Chicago Commission on Race Relations. His research ultimately became The Negro in Chicago, the first of numerous published 20th Century studies of the cause’s urban riots and their consequences. This highly acclaimed study led in 1921 to Dr. Johnson being appointed director of research for the National Urban League. In 1923 Johnson founded its professional magazine, Opportunity, and became its first editor. Opportunity published a wide variety of social science research and popular essays which revealed the impact Jim Crow on the African American community at that time.

In 1928, Dr. Johnson decided to move to Fisk University to continue his research and to become its first chairman of the newly established Department of Social Sciences. He viewed the move to a black institution as strengthening his scholarly work by enabling him to acquire more white philanthropic research funding. Upon receiving the funding he expected Johnson established the Fisk Institute of Race Relations, first “think tank” at a predominately black institution. In recognition of his efforts to place Fisk University on the academic map, the institution’s board of trustees, in 1948, appointed him the first black president of Fisk University. Dr. Johnson served in this capacity, did further innovative research, and received many accolades and honors until his death in Nashville on October 27, 1956.

Interesting to note that Fisk, one of the nation’s foremost HBCUs didn’t have a black president until 1948.

We stand on the shoulders of those who came before us. If we don’t know our history, we can’t understand where we are today, and where we still have to go.

We still have a long way to go.

Cross-posted from Black Kos