/

Advances in computer technology and the Internet have changed the way America works, learns, and communicates. The Internet has become an integral part of America’s economic, political, and social life. – Bill Clinton

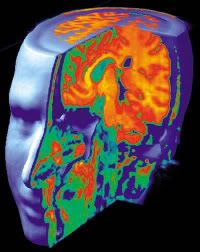

The scientific community has been asking for years now whether the Internet makes us smarter or dumber, and there are good arguments on both sides of the issue. Undoubtedly our use of the Internet has increased certain skills and abilities as we are forced to rapidly adjust to a wealth of incoming information and stimuli. Maybe there is no simple answer to this question. Evidence of Internet users’ distractibility and use of scanning techniques on websites has been documented for over a decade, and now more and more emerging research points to the conclusion that the Internet is rewiring our brains, to the detriment of some of our most valued abilities as a species. Recent research indicates that our use of the Web is making us increasingly distractable and less capable of effectively processing and absorbing what we read. In other words, we are creating a sort of attention deficit in ourselves, which is slowly deteriorating our ability to engage in complex thought processes that don’t involve multitudes of attention-grabbing stimuli.

2008 saw the publication of an article describing changes in the way ‘Net surfers read and process.

. . .a recently published study of online research habits, conducted by scholars from University College London, suggests that we may well be in the midst of a sea change in the way we read and think. As part of the five-year research program, the scholars examined computer logs documenting the behavior of visitors to two popular research sites, one operated by the British Library and one by a U.K. educational consortium, that provide access to journal articles, e-books, and other sources of written information. They found that people using the sites exhibited “a form of skimming activity,” hopping from one source to another and rarely returning to any source they’d already visited. They typically read no more than one or two pages of an article or book before they would “bounce” out to another site. Sometimes they’d save a long article, but there’s no evidence that they ever went back and actually read it. The authors of the study report:

It is clear that users are not reading online in the traditional sense; indeed there are signs that new forms of “reading” are emerging as users “power browse” horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins. It almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.

The Atlantic, emphasis added

The picture emerging from the research is deeply troubling, at least to anyone who values the depth, rather than just the velocity, of human thought. People who read text studded with links, the studies show, comprehend less than those who read traditional linear text. People who watch busy multimedia presentations remember less than those who take in information in a more sedate and focused manner. People who are continually distracted by emails, alerts and other messages understand less than those who are able to concentrate. And people who juggle many tasks are less creative and less productive than those who do one thing at a time.

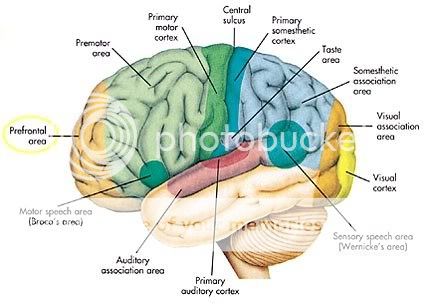

The common thread in these disabilities is the division of attention. The richness of our thoughts, our memories and even our personalities hinges on our ability to focus the mind and sustain concentration. Only when we pay deep attention to a new piece of information are we able to associate it “meaningfully and systematically with knowledge already well established in memory,” writes the Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel. Such associations are essential to mastering complex concepts.

Ms. Greenfield concluded that “every medium develops some cognitive skills at the expense of others.” Our growing use of screen-based media, she said, has strengthened visual-spatial intelligence, which can improve the ability to do jobs that involve keeping track of lots of simultaneous signals, like air traffic control. But that has been accompanied by “new weaknesses in higher-order cognitive processes,” including “abstract vocabulary, mindfulness, reflection, inductive problem solving, critical thinking, and imagination.” We’re becoming, in a word, shallower.

In another experiment, recently conducted at Stanford University’s Communication Between Humans and Interactive Media Lab, a team of researchers gave various cognitive tests to 49 people who do a lot of media multitasking and 52 people who multitask much less frequently. The heavy multitaskers performed poorly on all the tests. They were more easily distracted, had less control over their attention, and were much less able to distinguish important information from trivia.

The researchers were surprised by the results. They had expected that the intensive multitaskers would have gained some unique mental advantages from all their on-screen juggling. But that wasn’t the case. In fact, the heavy multitaskers weren’t even good at multitasking. They were considerably less adept at switching between tasks than the more infrequent multitaskers. “Everything distracts them,” observed Clifford Nass, the professor who heads the Stanford lab.

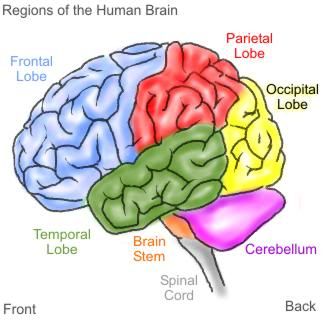

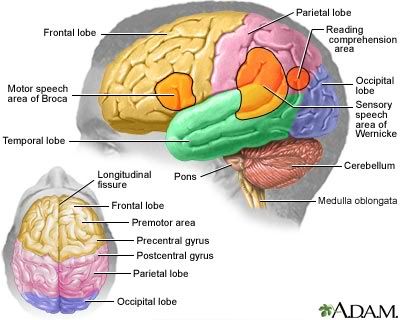

It would be one thing if the ill effects went away as soon as we turned off our computers and cellphones. But they don’t. The cellular structure of the human brain, scientists have discovered, adapts readily to the tools we use, including those for finding, storing and sharing information. By changing our habits of mind, each new technology strengthens certain neural pathways and weakens others. The cellular alterations continue to shape the way we think even when we’re not using the technology.

The pioneering neuroscientist Michael Merzenich believes our brains are being “massively remodeled” by our ever-intensifying use of the Web and related media. In the 1970s and 1980s, Mr. Merzenich, now a professor emeritus at the University of California in San Francisco, conducted a famous series of experiments on primate brains that revealed how extensively and quickly neural circuits change in response to experience. When, for example, Mr. Merzenich rearranged the nerves in a monkey’s hand, the nerve cells in the animal’s sensory cortex quickly reorganized themselves to create a new “mental map” of the hand.

Reading a long sequence of pages helps us develop a rare kind of mental discipline. The innate bias of the human brain, after all, is to be distracted. Our predisposition is to be aware of as much of what’s going on around us as possible. Our fast-paced, reflexive shifts in focus were once crucial to our survival. They reduced the odds that a predator would take us by surprise or that we’d overlook a nearby source of food.

To read a book is to practice an unnatural process of thought. It requires us to place ourselves at what T. S. Eliot, in his poem “Four Quartets,” called “the still point of the turning world.” We have to forge or strengthen the neural links needed to counter our instinctive distractedness, thereby gaining greater control over our attention and our mind.

It is this control, this mental discipline, that we are at risk of losing as we spend ever more time scanning and skimming online.

http://online.wsj.com/article/…

“We are not only what we read,” says Maryanne Wolf, a developmental psychologist at Tufts University and the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. “We are how we read.” Wolf worries that the style of reading promoted by the Net, a style that puts “efficiency” and “immediacy” above all else, may be weakening our capacity for the kind of deep reading that emerged when an earlier technology, the printing press, made long and complex works of prose commonplace. When we read online, she says, we tend to become “mere decoders of information.” Our ability to interpret text, to make the rich mental connections that form when we read deeply and without distraction, remains largely disengaged.

As we use what the sociologist Daniel Bell has called our “intellectual technologies”-the tools that extend our mental rather than our physical capacities-we inevitably begin to take on the qualities of those technologies.

http://www.theatlantic.com/mag…

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v…