Hey Moose! Just dropping by to say ‘hello’. I’ve been lurking about as much as I can, but far too busy for blogging lately with the whole school, work, and kids thing going on. Still, I miss the Purple Palace something fierce* so I wanted to drop this little thing I’ve been working on. If you like music, history, cultural geography, or even if you just want to spend a few minutes not thinking about Syria, well this is the post for you.

*see what I did there?

Obviously, I wrote this for a different format, so I didn’t bother with html links for the individual citations and whatnot. If anyone wants the full list of references, or more information about any of them, just make a request in the comments. I’m happy to kick down the goods.

–fogiv

The uniquely American musical form known as ‘the Blues’ represents perhaps the most powerful reflection of the trials and travails that were critical in shaping the African American experience in America. Originating from the cultural influences of both Africa and Europe, this surprisingly simple musical form mixes the sorrow and pain of slavery, as well as the joys of emancipation and freedom, and recollects the long struggle for equality in the face of discrimination and prejudice.

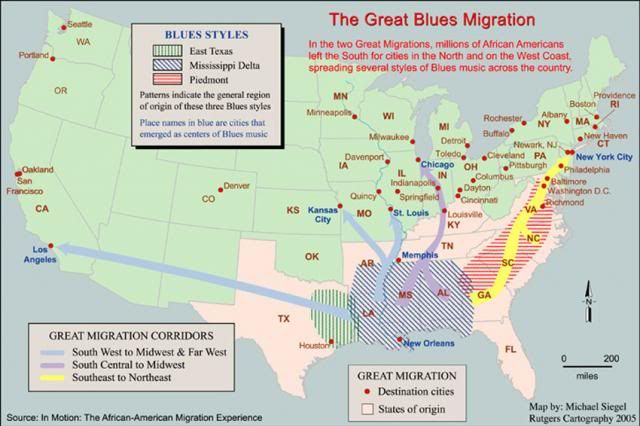

Tracing the geography of the Blues from its seminal roots in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta, and along its subsequent spread north and west across the of United States with the Great Migration, this musical tradition has unquestionably spawned or influenced almost all genres of modern American music, which have in turn influenced people and cultures all around the globe.

Thought by musicologists, historians, and relevant scholars of virtually every stripe to be America’s only uniquely original musical form, the Blues chart the movement of a people, the development of their culture, and record the genuine experience of African Americans while continuing to serve as the foundation for nearly all genres of American music–from rock and roll to hip-hop, and from to jazz to country, western swing, and bluegrass.

The geography of this music traces the journey of an enslaved people from the distant shores of western Africa to the slavery-supported agrarian South, and from its seminal roots in the turn-of-the century Mississippi Delta to its expansion across both time and space to the socioeconomic problems that still occur within deteriorating urban centers across the contemporary United States. Along this course, the Blues reflect the African American experience–and by extension the history of America–in a way that nothing else can.

Known widely as the ‘Father of the Blues’, W.C. Handy recalled his 1903 encounter with the Blues style on a Southern train platform:

“A lean, loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. The effect was unforgettable” (Handy & Bontemps, 1941).

The Blues are deeply entwined with the African American identity, and can be characterized both as looking forward to a more hopeful future, while keeping a distrustful eye affixed on the painful memories of the past. The music is festooned with reminders of the tragedies and inequalities that African Americans suffered–from the bondage of slavery to emancipation after the Civil War, and from that freedom to the enduring struggle for equality.

In terms of technical structure, the Blues is a musical form built around the use of ‘blue’ notes (i.e. a flatted or minor note), typically the third and/or seventh note of a scale, occurring where a major interval would be expected. These ‘blue’ notes have the effect of infusing the overall composition with a characteristic ‘sad’ sound, and with lyrics (or instrumental solos) that employ a repetitive rhyming scheme adhering to a twelve-bar structure–together comprising the essential Blues formula. (“ARTSEDGE: Blues Journey”, 2013). Clearly, the Blues are much more than the simplicity of their structural form implies, and is a musical form that carries with it a deeply ingrained cultural relevance. Famed harmonica player Sonny Terry once described the Blues as “…the closest music to our humanity–it’s like a folk music that rises up out of a culture” (“SearchQuotes”, n.d.).

Indeed, for it was upon the percussive and rhythmic cadences of traditional African music that the field ‘hollers’ and work songs of African American slaves were based, taking shape as antecedents to the Blues. According to influential ethnomusicologist, archivist, and field recorder Alan Lomax, “the earliest accounts of Negroes in Africa …spoke not so much of their pure singing, but of their singing in rhythm as they danced and as they worked” (Cohen, 2003). When slaves arrived in the New World, they faced unfathomable hardships and relentless toil in an utterly foreign environment, which bolstered the need to sustain their oral and musical traditions (Miller, 2002).

Born of this need, hollers and work songs sought to provide a sort of rhythmic momentum to the strenuous labor, and sought to lighten the otherwise unbearable working conditions (Nall, 2001). Field hollers were a ‘call and response’ style of song that developed in the fields of Southern plantations, helping provide rhythm to the drudgery of servitude. Legendary Bluesman Son House told an interviewer:

“People keep asking me where the blues started and all I can say is that when I was a boy we always was singing in the fields. Not real singing, you know, just hollerin’, but we made up our songs about things that was happening to us at the time, and I think that’s where the blues started” (Cohn, 1993).

Like hollers, work songs were also antecedent to the Blues forms that would later develop. Work songs generally involved an entire group as an instrument, with a lead singer or singers announcing a beginning verse line, while the laborers accompanied and/or refrained with percussive stomps or rhythmic sounds made with tools, or even simply a chorus of “oooh” and “hmmm” (Miller, 2002). This latter structure is exemplified well in the prison work song “Ain’t No More Cane on this Brazos,” which is similar to the slow, easy rhythms of a cotton chopping or other agricultural labor song (Cohen, 2003; Miller, 2002). Railroad work songs would typically be faster paced, and employ the syncopated rhythm of tools (Palmer, 1981; Strait, 2010). The meter of these songs would prove a strong influence in the development of the early Blues (Miller, 2002).

After emancipation, slaves found themselves enjoying a novel social circumstance: a modicum of leisure time. This change would prove to be an important catalyst in the continuing development of the blues musical form. As work songs waned, songs developed mostly for entertainment began to take their place, and these early Blues served a social function different from their antecedents (Wardlow, 1998). This style, which emerged in the late nineteenth century, came to be known as the country blues and was adopted by vagabonds, sharecroppers, and prisoners alike (Monod, 2007; Nall, 2001; Wardlow, 1998).

From its cradle in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta, the Blues spread along with the relocation of more than 6 million African Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North, Midwest and West from 1916 to 1970 in an event known as The Great Migration (Lewis, 2013). The subsequent development of the music followed the migration patterns of African Americans out of the rural South toward northern cities (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Great Blues Migration.

Motivated by inadequate economic opportunity, violent racism, and harsh segregationist laws, many African Americans fled northward to capitalize on the growing need for industrial labor that first arose during the World War I. One such migrant recalled life in the Mississippi Delta region during the 1930s in this way:

“In those days, it was ‘Kill a mule, buy another; kill a nigger, hire another.’ They had to have a license to kill anything but a nigger. We was always in season” (Scheper-Hughes & Bourgois, 2004).

As the Great Migration began, countless African Americans moved from one place to another in search of work. Blues musicians were themselves often migrant workers–serving in levee and lumber camps, trailing seasonal crop harvests, and providing services in boomtowns along the Mississippi River (Nall, 2001; Strait, 2010). Driven by the abject poverty of the period, Blues musicians and their songs reflected the starkness of their lives. Songs about floods, droughts, debt, travel, loved ones left behind, the toil of raising cotton and other crops were common subjects (Monod, 2007; Nall, 2001). For example, “Times Is Gettin’ Harder” (a 1940 recording of an older composition by Luscious Curtis) clearly notes the racial injustice and economic hardships of the post-emancipation South, which is referenced by the line ‘cotton and corn’:

Times is gettin’ harder,

Money’s gettin’ scarce.

Soon as I gather my cotton and corn,

I’m bound to leave this place.

White folks sittin’ in the parlor,

Eatin’ that cake and cream,

Nigger’s way down to the kitchen,

Squabblin’ over turnip greens.

The journey northward for African Americans was fraught with danger, and despite gaining the admiration of some whites for their talents, practitioners of the Blues had no exceptions. According to Pearson (2003), traveling musicians were “vulnerable to vigilante violence, police rip-offs, the county farm, being stranded, simply getting lost, or dealing with segregation by being refused service.” Life on the move, however difficult, did bring two tangible forms of freedom–travel and greater choice in sexual partners, both of which became central to the blues tradition (Palmer, 1981; Pearson, 2003; Strait, 2010).

The freedom of mobility was obviously a key element in any strategy seeking to improve standards of living, occupational stature, and social relations. It was a good thing to be ‘on the move’, and as a result physical mobility was a powerful symbol of one’s longing for a change in a life seemingly full of misfortune. One such example is expressed in Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Bad Luck Blues”:

Sister, you catch the Katy, I’ll catch the Santa Fe,

Doggone my bad luck soul,

Sister, you catch that Katy and I’ll catch that Santa Fe,

I mean Santa, speakin’ about Fe,

When you get to Denver, pretty mama, look around for me.

Note Jefferson’s mention of the ‘Santa Fe’ train. Before widespread automobile ownership, migration from the South generally followed rail routes (Strait, 2010). A common theme in much of the early Blues, mobility and travel are often expressed in songs through lyrics that evince the methods of transportation, particularly rail (Figure 2). As they moved, migrants carried the blues traditions of the Deep South and the Delta to urban centers such as Memphis, Atlanta, Houston, Dallas, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, and Chicago (Nall, 2001; Wardlow, 1998). Upon arrival in these urban centers African Americans often found poor working conditions, fierce competition for adequate housing, and little or no relief from the pains of prejudice (Lewis, 2013).

Figure 2. Men, women, and families waiting for the train north at the Union Railroad Depot in Jacksonville, Florida, 1921.

Railroads were often a central theme in the Blues and became an enduring folk symbol in African American culture, representing both physical escape and spiritual freedom. The Illinois Central Railroad, which ran from New Orleans to Chicago, transported hundreds of thousands of African Americans fleeing the Mississippi Delta and other parts of the South during the Great Migration (Green, 2005; Lewis, 2013). Other lines such as the Central of Georgia and the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroads (known colloquially as the ‘Yellow Dog’) linked other southern states to the Illinois Central lines, often providing the easiest and most affordable passage north into Chicago (Figure 3). References to the Yellow Dog appear in many early blues songs, including those of now legendary performers such as Charlie Patton, Lucille Bogan, and Big Bill Broonzy. Notable songs that feature trains and railroads prominently include Blind Willie McTell’s “B & O Blues, No. 2” (1933), Robert Johnson’s “Love in Vain” (1937), Bukka White’s “Special Steamline” (1940), Mississippi Fred McDowell’s “Freight Train Blues” (1959).

Migrants would often travel north to Ohio on the Louisville, and the Illinois Central, which could be taken from New Orleans to Chicago, providing routes out of much of the Delta blues country (Nall, 2001). The Illinois Central, also informally referred to as the ‘Fried Chicken Special’ after the pack lunches people brought along, was essential in affecting the Great Migration, but also as a means of return to the South to visit the friends and family left behind, seek refuge from the northern cold, or simply escape from the difficulties encountered in Northern cities. Tampa Red’s “I.C. Moan Blues” (1930) is a specific reference to the Illinois Central Railroad:

Nobody knows that I.C. like I do,

Now the reason I know, I’ve rode it through and through.

That I.C. Special is the only train I choose,

That’s the train I ride when I get these I.C. blues.

Mr. I.C. engineer, make that whistle moan,

I’ve got the I.C. blues and I just can’t help but groan.

Figure 3. Train Routes during the Great Migration, c. 1920.

The popularity of Chicago as a destination for migrants rested in part on the scope of the Illinois Central Railroad network, and contributed to the Windy City’s development as the undisputed capital of the Blues (Grossman, 2005; Nall, 2001). By the time World War I opened employment opportunities, the Illinois Central and adjoining lines penetrated many of the plantation regions where the African American population was most concentrated. Other railroad lines also offered access to Chicago from the South. Prior to 1916, most migrants to Chicago were likely to have roots in the upper South, but after that the city drew much its African American population from the Deep South, particularly Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia (Grossman, 2005).

Once automobiles became more widely available, Highways also became powerful symbols freedom from hardship and poverty in the South (Palmer, 1981). Perhaps no highway is as storied as U. S. Highway 61–which rivals U.S. Route 66 as the most famous road in American musical lore (Nall, 2001; Thom, 2002). The former, also now commonly referred to as ‘The Blues Highway,’ connected the Mississippi Delta region to the industrial economies of the North, and was a particular inspiration to blues musicians. The original road began in New Orleans, and wound its way northward as it passed though notable Blues communities like Clarksdale, Mississippi, Memphis, Tennessee, and Chicago, Illinois (Palmer, 1981; Thom, 2002). Scores of noteworthy blues musicians have composed songs about Highway 61, including Mississippi Fred McDowell, James “Son” Thomas, “Honeyboy” Edwards, Charlie Musselwhite, Eddie Burns, Big Joe Williams, Eddie Shaw, and Johnny Young.

In 1932, blues pianist Roosevelt Sykes was the first to record a song specifically about Highway 61, though Jack Kelly and his South Memphis Jug Band cut their own “Highway 61 Blues” only a year later (“Mississippi Blues Trail”, n.d.). Several now-famous Blues artists lived along or near Highway 61, including Charlie Patton, Robert Johnson, Son House, Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and B. B. King (“Mississippi Blues Trail”, n.d.).

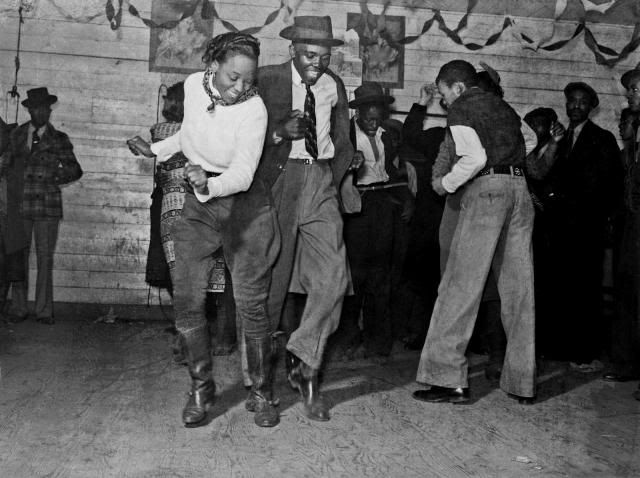

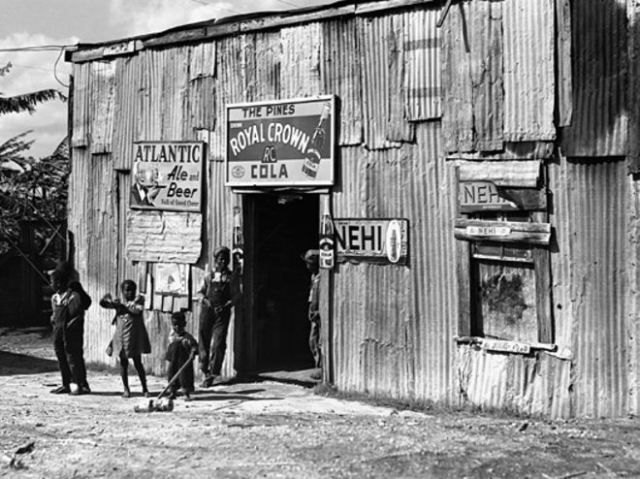

With the growth of the blues came the spread of a phenomenon known as the “juke joint.” Juke joints were simple, often makeshift buildings that served as social clubs and became breeding grounds within which the blues both developed and spread (Wilson, 2003).

Figure 4. Juke Joint, Mississippi, date unknown.

According to Crevar (2013), “blues luminaries like Charley Patton, Robert Johnson and Sonny Boy Williamson traveled across the South, guitar or harmonica in hand, from joint to joint for just enough money and food to get to the next one.” These traveling musicians would borrow and adapt both the music and lyrics of songs, and musical techniques and styles were emulated and elaborated upon (Palmer, 1981; Wilson, 2003).

From its inception, and as a result of the transit of the Blues over time and space, relatively distinct regional styles of the musical form developed–both in terms of technical musical execution, and in the lyrical content of the compositions. For example, songs developed in the country blues styles of the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta and Piedmont–the plateau region between the Atlantic Coastal Plain and the Appalachian Mountains–usually echo the experiences of African Americans in the post-emancipation South, while the urban blues tend to portray their post-migration urban experiences.

Still, the assignment of technical styles, specific blues musicians, and individual songs can be a tricky proposition because as Davis (1995) notes, “the widespread availability of country blues records quickly blurred regional distinctions that were fuzzy to begin with, on account of the nomadic existence of most blues performers.” Despite the inherent difficulties, some clear distinctions in style can still be made relative to geographic region, chiefly among the early Blues of the Mississippi Delta, Chicago, Piedmont, and Texas regions.

By nearly universal consensus, the blues of born of the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta are considered seminal to the form, and most notably in the pre-World War II era recordings of legends like Charlie Patton, Robert Johnson, and Son House (Thom, 2002).

The Delta Blues are characterized by individuals playing solo, accompanying themselves on guitar (not infrequently utilizing slide techniques) while passionately singing about their lives, experiences, and troubled times (Strait, 2010). Thought to have evolved among the work gangs of the cotton fields, prison farms and levee camps, later refined in juke joints, and spread via traveling musicians, it is the Delta Blues that endow the overall form with its most stereotypical imagery: the tormented Bluesman, soul bargained away at some mythical crossroads, “hunched over his acoustic guitar, exorcising the demons from the depths of his soul” (Davis, 1995; Thom, 2002).

While Charlie Patton (1891-1934) is generally acknowledged as the “Father of the Delta Blues,” no discussion of this regional style can be complete without mention of Robert Johnson, whose mythology is unquestionably iconic, even within contemporary American culture. Mythology aside, Johnson’s innovative style was instrumental in transmitting older musical styles into a new era (Brown, 2006; Palmer, 1981). Johnson’s “Crossroad Blues” (1936) is at once emblematic of both the Delta style and the mythology that surrounds it.

Arguably, the most influential link between the Delta and Chicago Blues styles was McKinley Morganfield (1915-1983), a tractor operator from Rolling Fork, Mississippi famously known as Muddy Waters (Lamplugh, 2012). In early 1940s, Waters played in local juke joints–one of which was his own residence–before moving north to Chicago in 1943 after being recorded for the first time by musicologist Alan Lomax (Palmer, 1981). The Delta style was innovated upon as musicians like waters replaced their acoustic instruments with amplified electric guitars and the traditional single performer / duo format was expanded into full bands including bass guitar, drums, and sometimes complete horn sections (Davis, 1995; Palmer, 1981). Eventually, the Chicago blues evolved beyond the standard six-note blues scale to incorporate major scale notes (Gordon, 2013). Waters’ “Hoochie Coochie Man” (1954) is among the most well known examples of the more full-bodied Chicago blues style.

The Piedmont Blues style refers to the region from whence it sprang. Geographically, the Piedmont refers the foothills of the Appalachians west of the tidewater region and Atlantic coastal plain stretching roughly from Richmond, Virginia, to Atlanta, Georgia. However, while this style was initially developed in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia, it was shared by musicians from as far afield as Florida, Delaware, and Maryland (“Piedmont Blues”, 2013). Integrating ragtime, European folk influences, and country dance songs, the highly-syncopated Piedmont guitar style employs a complex fingerpicking method in which a regular, alternating-thumb bass pattern under girds a melody produced on the higher pitched treble strings (Davis, 1995; Lamplugh, 2012; “Piedmont Blues”, 2013).

The blending of this diversity of various influences may owe to the fact that there were fewer restrictions on the physical mobility of African Americans in the Piedmont region than in other parts of the American South (Lamplugh, 2012). According to Davis (1995), songs in the Piedmont Blues style were “more genuinely songlike” than Delta or Texas blues, and their most striking characteristics were “wistfulness and instrumental virtuosity.” (Lamplugh, 2012). Classic examples of this style are represented in Blind Willie McTell’s “Statesboro Blues” (1928), Mississippi John Hurt’s “Nobody’s Dirty Business” (1928), and in the playing of Bowling Green John Cephas’ version of Memphis Minnie’s “Black Rat Swing”.

Interestingly, the presence of the Appalachian Mountains as a geographic barrier probably hindered the mixing of the distinct Delta and Piedmont Blues styles, as migrants along the Atlantic seaboard carried the Piedmont style up the coast to congregate in cities like New York or Philadelphia while the Delta style moved more directly northward into Memphis, Kansas City, St. Louis, and perhaps most prominently, Chicago (Nall, 2001).

Though undoubtedly derived from the Delta style, the Texas Blues are generally considered to be a more refined form of the Blues in terms of structure. As with other related styles, the guitar plays a central role in this regional style, complimenting the often direct lyrics with sophisticated variations or ‘runs’ from verse to verse with a laid-back, swing-oriented, or shuffling feel (“Blues Guitar”, n.d.; Davis 1995). The Texas style probably began to diverge from its parent style in the mid-1920s while still retaining the standard characteristics of the general country blues. After the World War II, the Texas Blues became electrified and amplified, and often featured jazz influenced, single-string soloing (Thom, 2002).

Blind Lemon Jefferson, a pioneer of the Texas Blues, demonstrates the roots of the Texas style well in his “Black Snake Moan” (1927). Another determining influence to this style was Hudy William Ledbetter (widely known as Leadbelly), whose 12-string guitar compositions such as “Midnight Special” have influenced countless musicians in subsequent generations (“Blues Guitar”, n.d.). Later, Houston-based Sam John Lightnin’ Hopkins (who had originally been influenced by Blind Lemon Jefferson) would go on record classic Texas Blues shuffle tunes like “Mojo Hand”–having profound influence over other Texas musical luminaries like Stevie Ray Vaughn and Townes Van Zandt.

Through both British Invasion and American Folk revival of the 1960s, Americans became reacquainted with their own musical heritage and the influence of the music has unquestionably left an indelible mark on the world. The blues have either created or strongly influenced virtually all popular music, and these influences continue to shape music forms worldwide. The geography of American Blues music demonstrates that the effects of globalization are not an especially recent or necessarily modernized phenomenon. Technically, the antecedents of the blues music first began to be globalized with the Atlantic slave trade. The polyrhythms and tonalities of the West African musical traditions, and the subsequent cross-fertilization and synthesis of various European influences–including scale, folk traditions, and instruments–gave rise to a unique and innovative musical form. This form progressed from field hollers to work songs to early country blues.

Along with the Industrial Revolution, which enabled easier long distance communication, transportation, and cultural diffusion, the distinctive synthesizing of African American musical expression was ripe for dissemination. The emergence of Blues culture in the 1920s coincided with an increase in musical performance, and the advent of recording technology paralleled the dramatic growth of black urban enclaves during the Great Migration (Green, 2005). The Blues, as a syncretic art form, may best exemplify a significantly formative period of social history in the United States and, arguably, represent America’s most unique and powerful contribution to global popular culture.

10 comments