T here have been a number of public legal arguments regarding recent current events; the Troy Davis execution, the alleged extra-judicial assassination of Anwar al-Awlaki and the Murdoch investigations on both sides of the Atlantic.

here have been a number of public legal arguments regarding recent current events; the Troy Davis execution, the alleged extra-judicial assassination of Anwar al-Awlaki and the Murdoch investigations on both sides of the Atlantic.

There seems much well-informed, well-reasoned and well-intended opinion on the moral and ethical implications of these cases, and others, which is of the calibre of the the dialogues preserved of Greek and Roman legal arguments. There is considerable merit in these public discussions on justice and propriety under the law. But most of them seem to overlook a basic point that the ancients didn’t miss, and it is summed up best by the guy who would know:

There is no such thing as justice, in or out of court.

This runs counter to progressive wisdom, and rightly so, but it remains true. And it is not just because the law is imperfect and inconsistently applied, though that is certainly a fault we must constantly seek to remedy. Fundamentally the occasional and significant absence of justice, in specific individual cases, is a feature not a bug.

Roman Law is founded on a refreshingly brief corpus of twelve tablets from 450BC which were concluded with the following phrase Salus Populi Est Suprema Lex:

Latin: the welfare of an individual yields to that of the community.Salus Populi Est Suprema Lex Lloyd Duhaime

There seems to be a fundamental tenet in our tradition of law which suspends justice for the individual in the public interest; a moral and ethical question probably worthy of our consideration.

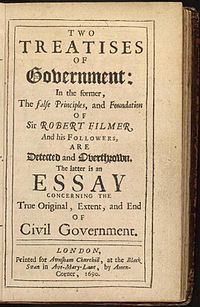

This legal dictum was noted by Cicero, who quoted it in De Legibus, and John Locke in Two Treatises of Government. It would seem to be a well-known precept among our legacy civic theorists:

Fourthly, for that which may concern the sovereign and estate. Judges ought above all to remember the conclusion of the Roman Twelve Tables; Salus populi suprema lex; and to know that laws, except they be in order to that end, are but things captious, and oracles not well inspired. Therefore it is an happy thing in a state, when kings and states do often consult with judges; and again, when judges do often consult with the king and state: the one, when there is matter of law, intervenient in business of state; the other, when there is some consideration of state, intervenient in matter of law.Francis Bacon – Of Judicature

Consider, “…the [kings and states,] when there is some consideration of state, intervenient in matter of law.” Isn’t this very thing claimed to be a mechanism of injustice? An oft-quoted modern judicial maxim illustrates this two-edged sword:

“Justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.”Lord Hewart (1870-1943), in Rex v. Sussex Justices, 1 King’s Bench Reports 256, at 259 (1924)

Indeed, but seen from the bleachers and the balcony, not necessarily from the dock. The judicial process is consequently often held above notions of actual innocence or guilt in specific cases, decisions for the justice “system” at the expense of individual “justice” (h/t Mets102):

This Court has never (emphasis in original) held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is “actually” innocent. Quite to the contrary, we have repeatedly left that question unresolved, while expressing considerable doubt that any claim based on alleged “actual innocence” is constitutionally cognizable.Justice Anthony Scalia – Supreme Court of the United States: In Re Troy Anthony Davis 17 Aug 2009

In this argument it is hard to see where the Constitution is being interpreted as providing a remedy for “innocence” once the process has been concluded. Another application of this basic precedence of the greater good over individual rights.

It might be asserted that any well-found polis, or aggregation of citizens sharing a common body of law, would have this underlying civic caveat in place. In this context the suspension of individual justice from time-to-time, especially in exceptional and idiosyncratic cases, is not just plausible, but arguably inevitable. Whether this is helpful in considering the merits of actions in the public square and courts of law I leave to the reader but it certainly seems to explain a lot.

28 comments