Ok, fresh off the tablet?

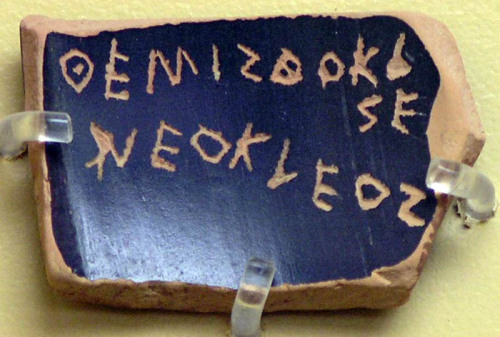

Democracy, as we currently conceive it, was the inspiration of an optimistic Enlightenment; drawing on a corpus of classical thinking which seemed virtuous or useful while tip-toeing around the thrones of reigning monarchs.In classical Athens, on any given day, the enfranchised citizens congregated on the Pynx to listen to their orators and demagogues on the issues and vote immediately with white and black pebbles. That form of direct democracy is reserved today for our juries, when we convene them, and the annual general meetings of our public companies and social clubs.

It is just as well, one might argue. The contemporary criticism of Athenian direct democracy was that it was “reckless and arbitrary.”

Arguable I suppose but Left Blogistan was in the back of my mind as much as Athens in that last remark.

Here comes the history lesson:

From the rebellions of 1848 constitutional monarchies in one form or another were de rigueur though arrived in various shapes and styles at the discretion or under the protest of respective princes; and largely leaving the army, the courts, foreign policy and the treasury in their hands.

Napoleon raised the stakes of war with his levée en masse and in his time no other monarch in Europe would have dared to attempt it. By the late 19th century, however, continental European states realised they must be able to raise huge citizen armies equipped with mass-produced bolt-action arms from the labour of the factories. The contract between the citizen and the state became mutually existential, much as it was in ancient Athens.

The emergence of the universal franchise, legislative regulation of working conditions and the nascent “labour” and “social democratic” parties among the Great Powers roughly parallels the development of huge, precise mobilisation plans by their respective general staffs. And long before the costs of entitlements like state sponsored health care, employment assurance or aged support existed, income taxes were imposed to mitigate military and naval armament costs. Marxism, gaining traction in these circumstances, recognized, indeed predicted, the trend towards social welfare while attempting to eliminate the middleman, namely the institutional actors whom were busily negotiating the terms of these contracts.

The consequences of the Great War radically altered these arrangements. The recalcitrant monarchies, which had failed to renew this bargain with their citizens, collapsed. Russians razed their state and erected a new collectivist one, terrifying the other Great Powers with the insidious influence on their polities of an alternate social arrangement.

Which lasted throughout the Cold War, it seems to me. But back to the narrative:

Households, in places whole communities, lost wage earners and patriarchs. The traditional guarantees of the extended working family and the protections afforded to their infirm by their own collective labour were undermined.The European states were saddled with massive war debts or repatriations and when the only national economy left standing collapsed it took the global economy along with it. It was no accident that by that decade most states had labour or socialist movements establishing extended entitlements to their citizenry. The terms of the pre-Great War contract were clearly no longer unacceptable. That democracy was an obsolete or inherently flawed system was not argued more effectively to a modern electorate than in Italy and Germany at this time.

So social entitlements joined representative democracy, conscription and income taxes in the grand bargain between the citizenry and the state.

I think I am going to be addressing some Randians, actually, Bond University has a bad reputation that way.

This arrangement, with minor adjustments, persevered for some time. When the joint chiefs realised, for example, as they did during the Second World War, that they needed middle-management and professionals as much as infantrymen, publicly funded tertiary education appeared.The Cold War, however, ended this bargain. Mutually Assured Destruction replaced mobilization as an imperative of total war and the disastrous, anachronistic, limited one in Viet-Nam nullified the contractual term of conscription. The existential threat was technological and the bulk of the population made little contribution except through the general revenue. The immediate existential components of the state bargain now wholly devolved to those President Eisenhower warned us about at the time and their terms, unsurprisingly, were profit motivated.

Soon after, in the late 1970s, wage growth erosion sets in just as the state regulatory framework imposed on corporate and financial enterprises peaks and begins to decline. The citizenry, prosperous by any historical measure, contentedly consume and the conventional wisdom of politics becomes President Clinton’s, “It’s the economy, stupid.” There is, in fact, little else.

Almost there, folks… One more to go.

Update: Toned down the “Randian” remark from the original.

4 comments