I’m only now beginning to catch up on the latest round of self questioning launched by Allison Benedikt’s reflective piece in The Awl about being a Jewish American growing up in Ohio, attending Zionist summer camp, visiting Israel, watching her sister move there, then dating and marrying a Non Jewish American.

There’s little doubt this piece has stirred the debate, intensified by Peter Beinart in his essay last year ‘The Failure of the Jewish American Establishment’ to another level, but that’s too big a topic to be covered here. And besides, what can I, as a non-American, non-Jew, say about it?

And herein lies the problem….

Part of Allison Benedikt’s disillusion about Israel was due to the angry questioning of her gentile husband, John Cook. In a response to Benedikt’s piece, Jeffrey Goldberg reserves most of his anger for him:

Essentially, the essay is about Benedikt falling out of love with the Zionist dream, which happens as she marries a non-Jew named John, who, by her description, spends a fair amount of time passing judgment on Israel…

The whole piece is written in a kind of faux-naive, I’m-so-lost voice that I found a bit grating….. When her husband acts like a self-righteous shit toward her sister, does she get a spine? Does she wonder why her husband hates Israel with such ferocity? Does she ever try to answer for herself why Israel exists? Or is she happy to subcontract out her thinking about the most important questions facing Jews first to her camp counselors, and then to her husband….

This is actually a very sad little essay that says more about the writer, who seems to have exchanged one simplistic narrative for another, than it does about Zionism or Israel.

(In a subsequent tweet exchange, the anger towards John Cook continues as Goldberg calls him a “bully and a jackass”.)

So my question is: how do Non Jews respond to this painful debate? Is it just an internal one, that should be left to Jews of all persuasions to sort out for themselves? Or is it incumbent – given the democratic progressive values which dominated Zionism from its inception – for Non-Jews to speak up for those values?

My attitude for years was to keep a discreet silence on these matters as a Non-Jew. From a part Armenian background, I’ve often been mistaken as Jewish since I was a kid (it still happens to this day – and I think I even confused Peter Beinart when we met ten years ago). I first visited Israel in 1970, and worked there in the 90s before Rabin’s assassination. As those who’ve followed any of my diaries know I have many British and American Jewish colleagues and friends (and several I’m proud to call friends on this blog). Sadly, I lost two to illness in the last year – two heroes of mine – Paul Miller and Tony Judt.

Both these men taught me so much – especially about silence and self censorship.

*

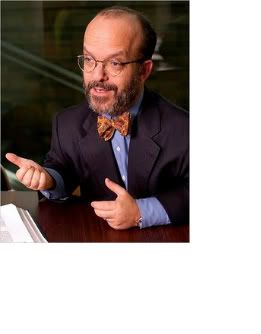

Paul Steven Miller‘s stupendous resume as civil rights leader, commissioner to the EEOC and a special adviser on political appointments to President Obama is evident for all to see, but let me just pass on one treasured memory which shows not only his amazing life force, humour and generosity of spirit, but how he dealt with the subject of silence and who should speak about what.

Paul Steven Miller‘s stupendous resume as civil rights leader, commissioner to the EEOC and a special adviser on political appointments to President Obama is evident for all to see, but let me just pass on one treasured memory which shows not only his amazing life force, humour and generosity of spirit, but how he dealt with the subject of silence and who should speak about what.

It was the last time I saw him in London. He’d just had an arm amputated because of the cancer which would eventually kill him, but he was irrepressible as ever, trying to juggle a new phone (he’d just lost one in a cab) and a bourbon only stopping to say: “Peter. Say something. It pisses me off. Haven’t you noticed I’ve lost an arm?”

He challenged my politically correct awkward silence, and we talked about what he’d been through. It wasn’t morose. It was occasionally painful. But it was a conversation about the unsayable which he feared having less than me. That was Paul’s way – he knew when to say things, and how to confront issues with honesty, clarity, and usually with life affirming humour.

An example of the latter, and Paul’s irreverence and sense of mischief. That night in London’s Soho was just after he’d met some senior British High Court judges, including one who is transsexual. He was impressed, but admitted he only just stopped himself saying:

So you’re a transsexual judge. Well, I’m a one-armed Jewish dwarf. Beat that!

While Paul wouldn’t let many things go unsaid, I knew Tony Judt for longer, and he constantly stressed that discussions about Israel and its connections to Jewish identity couldn’t just be had by Jews alone. In one of his last interviews before his untimely death last year he complained to me about the way the debate had been narrowed:

While Paul wouldn’t let many things go unsaid, I knew Tony Judt for longer, and he constantly stressed that discussions about Israel and its connections to Jewish identity couldn’t just be had by Jews alone. In one of his last interviews before his untimely death last year he complained to me about the way the debate had been narrowed:

Being Jewish is not enough. Being an ex-Zionist is not enough. But being an ex-Zionist who wore the Israeli army uniform (and has a pic of himself complete with cutie and sub-machine gun): that helped. And in this case the end justified the means. No one can shut me up on this subject, so they are forced to resort to clichés about self-hating Jews and the like: evidence of failure.

All the same, it does irritate me when I am described as a controversialist and commentator on Israel. I see myself as first and above all a teacher of history; next a writer of European history; next a commentator on European affairs; next a public intellectual voice within the American Left; and only then an occasional, opportunistic participant in the pained American discussion of the Jewish matter…

Tony found it limiting that his (self hating!) Jewishness became one of the defining things about his public persona in the last ten years. As a corollary to that prison of identity, he often insisted, at meetings and conferences, that people come out of their boxes, both to discuss things they didn’t know about (the whole essence of conversation surely) and so that we could all throw into relief our particular viewpoints. In the same interview he went on to say….

The influence of extremist Rabbis and the Anti-Defamation League worries me much more as a broader cultural phenomenon of (self-) censorship. As I have pointed out ad nauseam, I don’t lack platforms for my opinions so the problem is not the “silencing” of Judt. It is the closing of the Jewish mind here in America.

Though painful, I celebrate the discussions open up by Beinart, Goldberg and Benedikt as a sign that the Jewish American mind is returning to the tradition of openness, critical debate, self reflection and outward engagement.

Yet my question remains: what can Non Jews say in this context which is neither self-censorship, nor surrender to particularity, nor can be castigated as bullying and self righteous?

Or maybe the whole essence of debate, of conversation, of reaching out, is risking all the above.

..

(Crossposted to Daily Kos)

35 comments