Waco Lynch Mob May 15, 1916

I want to say first here that writing this disturbs me deeply. There will be text and images that are repugnant. “Lynching’ and its meaning for me as a black child in America was impressed upon me very early in life.

My parents felt that they had to sit me down and explain “lynching” because the subject came up at home during a discussion of “Strange Fruit” the Broadway Production in which my dad was a featured actor, written by Lillian Smith and directed by Jose Ferrer. I’ve written about it in the past in Strange Fruit Revisited.

They did not show me photos. Later on, I listened to Billie Holiday. Her lyrics and tone evoked what I could only imagine.

It wasn’t until I was older that I saw my first photo of “folks’ at a lynching, Posing smiling for the camera as if captured at a picnic. Old and young, male and female – all white.

I worried about our move to the deep south when I was 9. Discussed it with my mom who assured me it “was history”. I was not reassured, and my worries came back during a KKK scare that year.

As I grew older and faced ugly crowds with distorted faces during my days of civil rights activism and saw them on the tv news – rock throwers and spitters and epithet hurlers I often wondered about these people who seemed to live to hate, and hate to live.

Wondered how many of them had family scrapbooks containing postcards from the past – perhaps sent by grandma – portraying lynchings. I will never know.

The hate is not “past”. It lives on.

As a black person – I flinch when I see “lynching” taken out of its historical context.

For me it is both personal and political.

And so, today I’m writing about Waco, not the Waco you may only associate with Branch Davidian’s, not the Waco of today perhaps, but the Waco of 1916. The legacy of that day, 95 years ago, and of other lynchings lives on in its children and grandchildren – descendents of those who died and descendents of those who participated or simply stood idly by.

Never forget that.

Dee

““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““

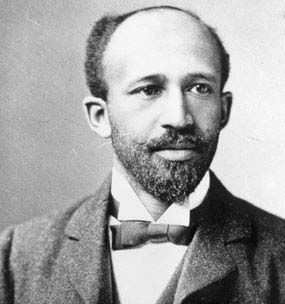

“The Waco Horror” was given its name by W. E. B. Du Bois, in the July 1916 issue of The Crisis, the news organ of the NAACP, which he edited.

W.E.B. DuBois.

DuBois and the NAACP would mount a campaign against lynching and document its depredations and terror, joined by anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells.

Ida B Wells

The reports on the events in Waco, on that ugly day were investigated by white suffragist Elizabeth Freeman who had no history of dealing with racial violence, and who had no idea what she would face in the aftermath of the lynching of Jesse Washington.

Elizabeth Freeman

In her book, The First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP, author Patrica Bernstein describes the picture above.

At first, the picture appears to be nothing more than a group of hundreds of men crowded into a city square, almost all of them wearing the flat-crowned straw “boater” hats that were popular in the summer of 1916. This ocean of flat-brimmed white hats is lapping against a scraggly little tree in the center of the square.

Only when you look closer do you see a fuzzy area in the center of the picture, below the tree, like a ribbon of smoke. And then, through the smoke, you can just make out . . . a leg, a foot, an elbow. A naked human being lies collapsed at the bottom of the tree on top of a smoldering pile of slats and kindling. Around his neck is a chain, which stretches up over a branch of the tree.

A man in a white shirt with a dark fedora mashed down on his head stands by the folded-up body, yanking on one end of the chain. He is wearing a heavy glove on the hand that holds the chain because it has been heated by the fire and is hot. This self-appointed executioner may have been caught in the act of jerking the blistered creature below the tree upright against the tree trunk in order to display him to the mob. Or perhaps he has just lowered his victim back into the fire. In the meantime, another man in white shirt and light-colored hat is poking and prodding the dying man with a stick or rod of some kind, almost as if he is trying to turn the body on the fire. The onlookers watch intently. Some appear to be smiling or shouting encouragement to the torturers.

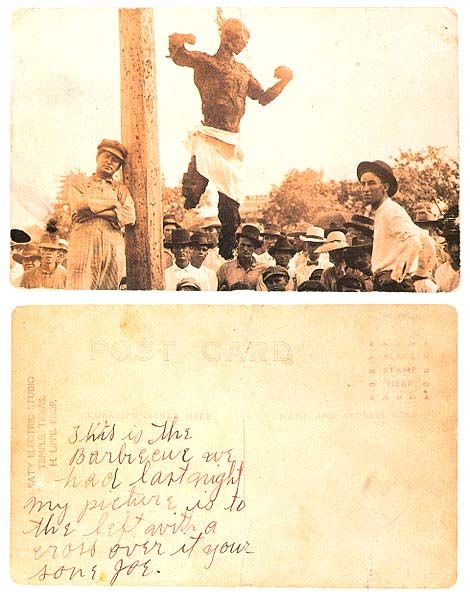

A postcard showing the burned body of Jesse Washington on display in Robinson, Texas, seven miles from the place of lynching in Waco. The back reads: “This is the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe.”

DuBois wrote a powerful editorial in The Crisis, using information sent to him by Freeman and others. I am going to quote liberally from it here. The entire piece can be read at The Waco Horror

From “The Waco Horror,” The Crisis, Vol. 12 (July 1916), supplement, pp. 1-8.]

A big fellow in the back of the court room yelled, ‘Get the Nigger!’ Barney Goldberg, one of the deputy sheriffs, told me that he did not know that Fleming had dropped orders to let them get the Negro, and pulled his revolver. Afterwards he got his friends to swear to an affidavit that he was not present. Fleming said he had sworn in fifty deputies. I asked him where they were. He asked, ‘Would you want to protect the nigger?’ The judge made no effort to stop the mob, although he had firearms in his desk.”

4. The Burning

“They dragged the boy down the stairs, put a chain around his body and hitched it to an automobile. The chain broke. The big fellow took the chain off the Negro under the cover of the crowd and wound it around his own wrist, so that the crowd jerking at the chain was jerking at the man’s wrist and he was holding the boy. The boy shrieked and struggled.

“The mob ripped the boy’s clothes off, cut them in bits and even cut the boy. Someone cut his ear off; someone else unsexed him. A little working for the firm of Goldstein and Mingle told me that she saw this done.”

“I went over the route the boy had been taken and saw that they dragged him between a quarter and a half a mile from the Court House to the bridge and then bragged him up two blocks and another block over to the City Hall.” After they had gotten him up to the bridge, someone said that a fire was already going up at City Hall, and they turned around and went back. Several people denied that this fire was going, but the photograph shows that it was. They got a little boy to light the fire.

“While a fire was being prepared of boxes, the naked boy was stabbed and the chain put over the tree. He tried to get away, but could not. He reached up to grab the chain and they cut off his fingers. The big man struck the bo

y on the back of the neck with a knife just as they were pulling him up on the tree. Mr. Lester thought that was practically the death blow. He was lowered into the fire several times by means of the chain around his neck. Someone said they would estimate the boy had about twenty-five stab wounds, none of them death-dealing.”

“About a quarter past one a fiend got the torso, lassoed it, hung a rope over the pummel of a saddle, and dragged it around through the streets of Waco.”

“Very little drinking was done.”

“The tree where the lynching occurred was right under the Mayor’s window. Mayor Dollins was standing in the window, not concerned about what they were doing to the boy, but that the tree would be destroyed. The Chief of Police also witnessed the lynching. The names of five of the leaders of the mob are known to this Association, and can be had on application by responsible parties.”

“Women and children saw the lynching. One man held up his little boy above the heads of the crowd so that he could see, and a little boy was in the very tree to which the colored boy was hung, where he stayed until the fire became too hot.”

Another account, in the Waco Times Herald, Monday night, says:

“Great masses of humanity flew as swiftly as possible through the streets of the city in order to be present at the bridge when the hanging took place, but when it was learned that the Negro was being taken to the City Hall law, crowds of men, women and children turned and hastened to the lawn.”

“On the way to the scene of the burning people on every hand took a hand in showing their feelings in the matter by striking the Negro with anything obtainable, some struck him with shovels, bricks, clubs, and others stabbed him and cut him until when he was strung up his body was a solid color of red, the blood of the many wounds inflicted covered him from head to foot.”

“Dry goods boxes and all kinds of inflammable material were gathered, and it required but an instant to convert this into seething flames. When the Negro was first hoisted into the air his tongue protruded from his mouth and his face was besmeared with blood.”

“Life was not extinct within the Negro’s body, although nearly so, when another chain was placed around his neck and thrown over the limb of a tree on the lawn, everybody trying to get to the Negro and have some part in his death. The infuriated mob then leaned the Negro, who was half alive and half dead, against the tree, he having just strength enough within his limbs to support him. As rapidly as possible the Negro was then jerked into the air at which a shout from thousands of throats went up on the morning air and dry goods boxes, excelsior, wood and every other article that would burn was then in evidence, appearing as if by magic. A huge dry goods box was then produced and filled to the top with all of the material that had been secured. The Negro’s body was swaying in the air, and all of the time a noise as of thousands was heard and the Negro’s body was lowered into the box.”

“No sooner had his body touched the box than people pressed forward, each eager to be the first to light the fire, matches were touched to the inflammable material and as smoke rapidly rose in the air, such a demonstration as of people gone mad was never heard before. Everybody pressed closer to get souvenirs of the affair. When they had finished with the Negro his body was mutilated.”

“Fingers, ears, pieces of clothing, toes and other parts of the Negro’s body were cut off by members of the mob that had crowded to the scene as if by magic when the word that the Negro had been taken in charge by the mob was heralded over the city. As the smoke rose to the heavens, the mass of people, numbering in the neighborhood of 10,000 crowding the City Hall law and overflowing the square, hanging from the windows of buildings, viewing the scene from the tops of

buildings and trees, set up a shout that was heard blocks away.”“Onlookers were hanging from the windows of the City Hall and every other building that commanded a sight of the burning, and as the Negro’s body commenced to burn, shouts of delight went up from the thousands of throats and apparently everybody demonstrated in some way their satisfaction at the retribution that was being visited upon the perpetrator of such a horrible crime, the worst in the annals of McLennan county’s history.”

“The body of the Negro was burned to a crisp, and was left for some time in the smoldering remains of the fire. Women and children who desired to view the scene were allowed to do so, the crowds parting to let them look on the scene: After some time the body of the Negro was jerked into the air where everybody could view the remains, and a might shout rose on the air. Photographer Gildersleeve made several pictures of the body as well as the large crowd which surrounded the scene

as spectators.”

The photographer knew where the lynching was to take place, and had his camera and

paraphernalia in the City Hall. He was called by telephone at the proper moment. He writes us:

“We have quite selling the mob photos, this step was taken because our ‘City dads’ objected on the grounds of ‘bad publicity,’ as we wanted to be boosters and not knockers, we agreed to stop all

sale.”“F.A. GILDERSLEEVE.”

Our agent continues: “While the torso of the boy was being dragged through the streets behind the horse, the limbs dropped off and the head was put on the stoop of a disreputable woman in the reservation district. Some little boys pulled out the teeth and sold them to some men for five dollars apiece. The chain was sold for twenty-five cents a link.”

“From the pictures, the boy was apparently a wonderfully built boy. The torso was taken to Robinson, hung to a tree, and shown off for a while, then they took it down again and dragged it back to town and put it on the fire again at five o’clock.”

DuBois goes on to document statistics for what he dubbed “the Lynching Industry”, with “Colored Men Lynched by Years, 1885-1916”, totaling 2843.

He closes with this statement:

What are we going to do about this record? The civilization of America is at stake. The sincerity of Christianity is challenged. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peoples proposes immediately to raise a fund of at least $10,000 to start a crusade against this modern barbarism. Already $2,000 is promised, conditional on our raising the whole amount.

Interested persons may write to Roy Nash, secretary, 70 Fifth Avenue, New York City.

Filmmaker Gode Davis died before he could complete his project

American Lynching: A Strange and Bitter Fruit

His website speaks of the early history of protest:

At first, voices raised in protest were few. African-American publisher and newspaper pamphleteer Ida B. Wells became a magnet for hateful attention by stridently opposing in print the lynchings of two personal friends, black grocers, in Memphis. Forced to leave town, she immediately launched an anti-lynching crusade that eventually brought her Don Quixote-like cause before the crowned heads of Europe – but brought influential hearings only rarely in her native United States. Other prominent voices daring to oppose lynching as spectacle included Samuel Langhorne Clemens, popularly known as Mark Twain, who penned the strident and accusatory The United States of Lyncherdom in 1901. Most instrumental in the decades-long anti-lynching campaign were leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founded in 1909. Founders of the NAACP included noted black scholar and activist W.E.B. DuBois and muckraking white author Charles Edward Russell. But leaders such as James Weldon Johnson and especially Walter F. White became the most influential. White, a light-skinned African-American, and his Euro

-American protégé Howard “Buck” Kester, demonstrated incredible personal courage by infiltrating lynch mobs and mobbism-oriented racist organizations to uncover little publicized details that served to expose the popularized pro-lynching mythos as a lie while documenting particular lynchings as the heinous American atrocities they truly were.

He points out that lynching was not simply a tactic for terrorizing blacks. Here is what he had to say about the killings of Mexicans, or Tejanos:

Racism and Texas also intersected for mob-led killings of brown-skinned people. During January of 1918, a mass lynching of this type occurred near a lonely place called Porvenir. “It means ‘future’ in Spanish,” says survivor and witness Juan Bonilla Flores, “But they stole our future.” Then a boy of 12 holding his father Longino’s nearly bullet-severed head in his forever-traumatized hands, Mr. Flores is now a leather-skinned centenarian. He remembers Porvenir when some forty local white ranchers and Texas Rangers came to his thriving village and summarily shot to death fifteen men and teenagers between the ages of 16 and 73 – like his father — all of them ‘tejanos’ – Texans of Mexican descent. “They killed us for our land,” he says before our cameras with a rueful smile, “and because we were Mexicans.” During a single decade, the gore-filled years between 1910 and 1920, up to 5,000 tejanos were similarly murdered. In 1910, for instance, 21-year-old cowboy Antonio Rodriguez was burned alive in Rock Springs, Texas after a mob accused him of murdering a white woman. As with African-Americans, the actual number of Latino victims will never be known. In fact, some of our affiliated scholars such as William Carrigan, Benjamin H. Johnson, Arturo Rosales, and Clive Webb believe that in terms of sheer numbers, the victims who were indigenous peoples including those considered to be “Mexican” approaches or even surpass the number of black victims.

Here is a brief clip from a presentation by Gode Davis:

Filmmaker Gode Davis on lynching:

Many of you may have read the book or seen the online exhibit Without Sanctuary, which documents “postcards” from lynchings.

For those of you who wish to do further research, on Waco, or lynching there are currently several books available including:

The Making of a Lynching Culture: Violence and Vigilantism in Central Texas 1836-1916 , by William Carrigan

And of course Bernstein’s:

The First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP

The past is not buried. Nor forgotten. Townspeople in Waco have a wide range of perspectives about efforts to shed light on this history and about calls for a modern day apology.

NPR reported this story back in 2006 Waco Recalls a 90-Year-Old ‘Horror’

“““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““`

“““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““`

There are times when I look at the twisted faces of today’s right-wingers driven by racial and ethnic animus, and read their comments scrawled around cyberspace, I think of the postcards of hate. I think of Waco. I wonder, how long it will take before our ugly legacy of lynching is buried in the sands of time?

——————————————————————————–

Cross-posted from Black Kos

15 comments