A wide-angle look at one of the – if not the – most important songs of the 20th Century, seventy-five years after its recording, following the jump …………

This is not the first account (nor the last) you may read that will examine the impact and legacy of the 1930’s anti-lynching song Strange Fruit – indeed, our own Denise Oliver Velez has a personal connection with the song, and it has been touched upon by several others … that you likely may be quite familiar with it.

Still, not everyone is familiar with it (nor with its back-story). Plus, I think its lineage (from poem to song to performance to recording to legacy) is one that deserves an overview with photos of the critical figures – and that is what I will attempt to do here. Whether this account is successful … you’ll have to be the judge.

——————————————————————————————

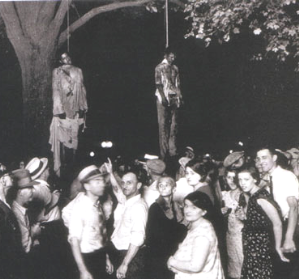

While it was the 1955 murder of Emmett Till that truly shook the nation to what was going on, it had been going on for decades. According to the Center for Constitutional Rights, between 1882 and 1968(!) mobs lynched 4,749 persons in the United States, over 70 percent of them African Americans. Often lynching photographs were sold as postcards if you can believe it.

Twenty-five years before the murder of Emmett Till, it was a 1930 photograph taken by Lawrence Beitler – of the lynchings of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana – that begins our Strange Fruit journey.

While many have recorded the song over the years (as will be recounted later) it was the Billie Holiday version that remains the definitive one to most. One more recent (instrumental) version was recorded by pianist Herbie Hancock and Marcus Miller (playing bass clarinet). And like most people, Marcus Miller assumed that – if Billie Holiday did not write the song herself – surely it was another African-American whose life was touched by this crime. (Especially if one sees the writer’s credit attributed to Lewis Allan).

It turns out that ‘Lewis Allan’ was the pseudonym for Abel Meeropol – an English teacher at DeWitt Clinton high school in the Bronx, New York. He adopted that nom-de-plume after two children he and his wife were expecting were stillborn – and they gave them the names … Lewis and Allan. Meeropol often wrote poetry and at times would ask others to write music for some of his poems.

But when he saw the image of that lynching mentioned above, he was upset enough to write his famous poem, and also the music for it (as it was that stirring). Various accounts have him publishing this poem in a 1937 teacher’s union publication first, then performing it at a teacher’s union meeting. Meeropol, his wife and the African-American vocalist Laura Duncan performed it at a Madison Square Garden rally one summer.

Let’s pause for a moment to look at the rest of the life of Abel Meeropol, who eventually left teaching and made his way to Hollywood following the success of Strange Fruit. Before he left, he was called before a New York legislative hearing, where he (who, like many teachers, had been a member of the Communist Party) was asked if the Party had paid him to write the song? He said no, that anti-racism was a trait held by many in the Party.

In Hollywood, he left the Communist Party and had one other notable song as part of his legacy. In 1945, he wrote a song about tolerance called The House I Live In – which was sung by Frank Sinatra – in a film short that later won an Academy Award.

One other part of his life should be noted. He and his wife Anne were attending a 1953 Christmas party at the home of civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois where they met two boys (ages six and ten) named Robert and Michael Rosenberg, the (now orphaned) sons of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg – who had been executed on espionage charges earlier (below photo left). In time, the two boys went to live with the Meeropols, who later adopted them (photo right, with Anne). Both became university professors, and are still alive and active in social issues today. Abel Meeropol died in 1986 of pneumonia at the age of 83.

Returning to the late 1930’s … accounts differ, but according to one account Abel Meeropol brought the song to the attention of Barney Josephson – the owner of Greenwich Village’s Café Society – believed to be New York’s first integrated nightclub. Josephson (photo left below) saw the power of the song … and knew just the performer to make it happen, whom he introduced to Abel Meeropol.

There has been so much written about the jazz singer Billie Holiday – some true, some arguable, some false – that it is beyond the scope of this essay to speak much about her. Indeed, another account of the song’s lineage is that her manager heard it at the Madison Square Garden performance and brought it to her attention first. Suffice it to say, the legacy of Billie Holiday (photo below right) as a singer during the golden age of jazz is secure. I agree with one writer who described her work as best heard on a Sunday morning … and I do at times.

She was fearful of performing the song – as the musician Marcus Miller notes, “The 60’s hadn’t happened yet. Things like that just weren’t talked about. They certainly weren’t sung about.” But because the imagery reminded her of her father, she made it a staple of her performances.

Barney Josephson had some house rules for her renditions:

1) It would be her closing tune, 2) no waiter service was available then, 3) the room would be in darkness but for a single spotlight on her, and 4) there would be no encore.

The next step was to have the song recorded … but Columbia Records was so fearful of reactions from record dealers in the South that it balked. Even her producer at Columbia, the legendary John Hammond – a civil rights advocate himself (photo left below) – did not want to be involved with the song (as he thought the imagery was too graphic and would harm her career).

She turned to the president of Commodore Records, which was a specialty label of the day that took on unusual recordings. Milt Gabler went on to a legendary career in the recording industry – enshrined in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as a non-performer – and his nephew Billy Crystal put together a documentary on his career (photo right).

Gabler is reported to have cried when Holiday sang the song unaccompanied to him and – after securing a release from Columbia Records for Billie to record one session out-of-contract – arranged for one of his subsidiary labels to release the song. Gabler, worried that the song was too short, asked her pianist to put together a longer intro, to build the scene for the vocals when it was recorded on April 20, 1939 in New York.

Billie Holiday’s recording eventually sold a million copies. In October 1939, Samuel Grafton of The New York Post described “Strange Fruit”: “If the anger of the exploited ever mounts high enough in the South, it now has its ‘Marseillaise’.” Yet for years, it was not spoken of much in black families (where the subject matter was too painful) and its appeal was limited to progressive northern and western cities. Unsurprisingly, it was banned from South African radio during the apartheid era.

After the Emmett Till murder and the beginning of the civil rights era, that began to change. Bob Dylan was among those listing it as a personal inspiration (his song Desolation Row refers to the 1930 photo that began the process) and the late Ahmet Ertegun (of Atlantic Records) considered it to be a “declaration of war – the beginning of the civil rights era”. Among those who have recorded the tune are Nina Simone, UB40, Jeff Buckley, Diana Ross, Lou Rawls, Sting, Josh White, Nona Hendryx, Tori Amos and Cassandra Wilson.

Seventy-five years later, the song’s legacy is strong. In 1999, Time Magazine called it the Song of the Century, then in 2002 the Library of Congress added it to its National Recording Registry and was voted as Number One in the 100 Songs of the South by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. A 1944 novel entitled Strange Fruit was later made into an opera – which premiered in 2007. A documentary by PBS in 2003 told the story of the song, and a 2000 book by David Margolick set the story in the framework of the Café Society.

Let’s close with Lady Day singing it ….. I prefer a re-recording she made of it in the 1950’s (with a better recording quality of the day).

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar treesPastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning fleshHere is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

5 comments