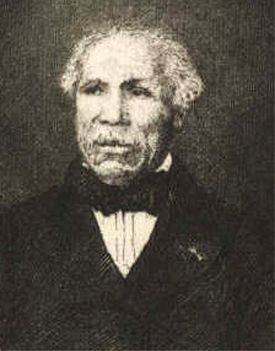

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

En Garde! Fencing and black fencing masters

I grew up with dreams and fantasies of fencing and swashbuckling, duels and derring do. As a child my dad played a musketeer in the cast of Cyrano de Bergerac on Broadway, starring Puerto Rican actor Jose Ferrer, and one of my cherished mementos is his dueling foil.

I buried my nose in the works of the black French author Alexandre Dumas, and in my head the three Musketeers were black. Little did I know at the time, that Dumas had modeled his Count of Monte Cristo on his father, Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, better known as Thomas-Alexandre Dumas.

Hollywood of course, never cast black actors in any of the many film versions of The Three Musketeers, and none of my school teachers ever bother to even mention Dumas was black, nor was fencing or dueling ever associated with black swordmasters. The closest the media ever got to portraying someone with an olive complexion and a sword was probably Zorro, and I used to imagine myself slashing away elegantly, making the sign of the Z.

It wasn’t until the 60’s when I took a class in stage fencing at Howard University, taught by a black-Native Canadian fencer Ricky Hawkshaw, that I learned more about the history of blacks who were masters of the sport. Blacks were associated with baseball, boxing, basketball and football – not dueling and épée.

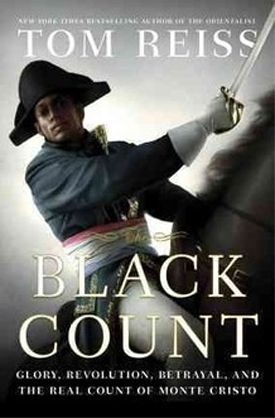

I was elated two years ago to discover the book by Tom Reiss The Black Count, which would expose Dumas’ life and history to a wider audience.

Here is the remarkable true story of the real Count of Monte Cristo – a stunning feat of historical sleuthing that brings to life the forgotten hero who inspired such classics as The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers.

The real-life protagonist of The Black Count, General Alex Dumas, is a man almost unknown today yet with a story that is strikingly familiar, because his son, the novelist Alexandre Dumas, used it to create some of the best loved heroes of literature.

Yet, hidden behind these swashbuckling adventures was an even more incredible secret: the real hero was the son of a black slave — who rose higher in the white world than any man of his race would before our own time.

Born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), Alex Dumas was briefly sold into bondage but made his way to Paris where he was schooled as a sword-fighting member of the French aristocracy. Enlisting as a private, he rose to command armies at the height of the Revolution, in an audacious campaign across Europe and the Middle East – until he met an implacable enemy he could not defeat.

The Black Count is simultaneously a riveting adventure story, a lushly textured evocation of 18th-century France, and a window into the modern world’s first multi-racial society. But it is also a heartbreaking story of the enduring bonds of love between a father and son.

The Reiss book re-awakened my historical interests in blacks and fencing and I learned of Jean-Louis Michel, “a fencing master, sometimes hailed as the foremost exponent of the art of fencing in the nineteenth century.”

My explorations led to early New Orleans, and an interesting article on “The Black fencer in Western Swordplay” featuring Michel among others, and then I set out to learn more about “the Black Austin” and fencing master Basile Croquere, about whom not much has been written.

A quadroon educated in Paris, Croquere gained a reputation for his well mannered, charming personality and skill as a dance master. Considered the handsomest man in New Orleans, Croquere was a man of many talents: a noted mathematician, teacher, carpenter known as the cleverest constructor of stairways in New Orleans, and the finest fencing master in the city. He taught fencing to the cream of Creole society but never fought a duel due to his race.

My music history classes had never included “The Black Mozart”, Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-George so I never knew anything about the most talented and deadly fencer/composer of his time.

A Fencing Champion and “God of Arms”

Henry Angelo, who ran a famous fencing academy in London, wrote an account Saint-George’s athletic prowess “Never did any man combine such suppleness with so much strength. He excelled in every physical exercise he took up, and was also an accomplished swimmer and skater…He could often be seen swimming across the Seine with only one arm, and in skating his skill exceeded everyone else’s. As to the pistol, he rarely missed the target. In running he was reputed to be one of the leading exponents in the whole of Europe”.

Inevitably the exotic prodigy Saint-George soon dazzled Parisian society and his company was fought over. When he was confronted, as he was from time to time, by jealous hostility, his charm and impeccable manners soon disarmed his opponent. Few would dare challenge him to a duel and on one occasion, when he was slapped by a well-known violinist, he declined to fight on the grounds that he had far too much respect for his opponent.

However in 1765 a master of arms from Rouen and former officer, named Picard, challenged Saint George to a duel with a racial insult calling him “La Boessiere’s mulatto”. Saint George declined, but his father insisted and promised him an English style cabriolet if he won. Saint George went to Rouen and easily defeated Picard. Picard was forced to acknowledge Saint George’s superior skills.

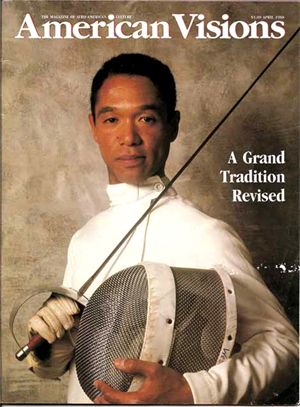

Fast forward to the modern day Olympics, and a young man named Peter Westbrook caught my interest in the 1970’s.

Peter Westbrook (born April 16, 1952) is a former American sabre fencing champion, active businessman and founder of the Peter Westbrook Foundation.As a former U.S. champion and Olympic medalist, Peter Westbrook came to fencing from an unlikely direction, the inner city. Westbrook’s remarkable life began with his Japanese mother, who convinced him to try fencing. As a Newark teenager in the 1960s, Westbrook brought unseen intensity to the sport; anger over his absentee father, poverty, and status as a biracial man in a racist society helped to fuel Westbrook to remarkable heights within the sport. Through discipline and hard work, he channeled his anger into the competitive edged needed to become an internationally ranked competitor.

Westbrook’s father, Ulysses, was a G.I. stationed in Japan during the Korean War; when he met Mariko, a beautiful Japanese woman from a sheltered home. Soon after their marriage they returned to the United States, traveling first to St. Louis, Missouri and eventually settling in Newark, NJ, where Peter and his younger sister Vivian were born. Peter’s earliest memories are of frequent bouts of domestic violence.

Peter was 4 when his father left, leaving his mother to raise the family with no real skills or outside means of support. Through a series of jobs, working in a factory and as a maid, she provided for her children. Mariko bartered with priests at the local Catholic school (St. Peters/Queen of Angels) in exchange for schooling for Peter and Vivian.

Harassed by the other children because of his mixed race and taught by his mother to “not cry, to work hard, to be ethical, and to fight to achieve our goals; And if we should survive the fight, she said, we should get up and fight some more,” the young Peter Westbrook became a very good fighter. His fencing career started at Essex Catholic High School, only because of his mother’s $5.00 bribe. Mariko knew that fencing would keep Peter out of trouble and, if he had any ability, bring him into contact with people who would expose him to a different world that the one he had been born into.

Following the career of Westbrook led me to a young black American woman, Ibtihaj Muhammad.

Muhammad today, lives the dreams I had as a child.

Ibtihaj Muhammad (born 4 December 1985) in Maplewood, New Jersey is an American sabre fencer and member of the United States fencing team. She is best known for being the first Muslim woman to compete for the United States in international competition.Muhammed was born in Maplewood, New Jersey, of African American descent. She was raised in a family with four siblings. As a Muslim female growing up in an athletic household, Muhammad always wore long clothing under her athletic uniforms to conform with Islam’s emphasis on modesty. Muhammad discovered fencing while driving past the local high school when her mother saw fencers who were covered from head to toe. Muhammad attended Columbia High School (New Jersey), a public high school, where she joined the fencing team at age

After fencing épée for a few years, Muhammad decided to switch to sabre at the request of her high school coach Frank Mustilli. She quickly developed in the weapon helping to lead her team to two state championships. In late 2002, Muhammad joined the prestigious Peter Westbrook Foundation, a program which utilizes the sport of fencing as a vehicle to develop life skills in young people from underserved communities. She was invited to train under the Westbrook Foundation’s Elite Athlete Program in New York City. She is coached by former PWF student and 2000 Sydney Olympian Ahki Spencer-El.

Meet Ibtihaj Muhammad:

She is currently training for 2016.

Muhammad is training for the 2016 Olympic Games in London where she could become likely the first Muslim U.S. woman to compete at the Olympic Games in a hijab. “When most people picture an Olympic fencer, they probably do not imagine a person like me. Fortunately, I am not most people. I have always believed that with hard work, dedication, and perseverance, I could one day walk with my U.S. teammates into Olympic history.” Muhammad says that fencing has taught her “how to aspire higher, sacrifice, work hard and overcome defeat. I want to compete in the Olympics for the United States to prove that nothing should hinder anyone from reaching their goals — not race, religion or gender. I want to set an example that anything is possible with perseverance.”

Right On Ibtihaj!

En Garde!

(Cross-posted from Black Kos)

3 comments