photo of 1977 Marie Laveau painting by Charles Massicot Gandolfo

Every year in two of my classes, I introduce students to the living history of Voudou-the religion, and its role in shaping the Caribbean island of Ayiti (Haiti) as well as in the Caribbean basin area of the U.S. in Louisiana-from Baton Rouge down to New Orleans.

In women’s studies, I include the myths and legends, as well as modern interest in Marie Laveau, known to practitioners and tourists as Queen Marie. Most of the students have been completely unfamiliar with her, and with the history and the roles of free women of color in Louisiana and throughout the south.

This year, much to my surprise, most students knew the name Marie Laveau (sometimes spelled Leveaux) simply because of a pop culture FX series “American Horror Story: Coven” which most of them have seen.

Events reveal a long-held rivalry between the witches of Salem and the Voodoo practitioners of New Orleans, as well as a historic grudge between Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau (Angela Bassett) and socialite serial killer Delphine LaLaurie (Kathy Bates). The primary theme of the season is oppression; specifically, the oppression of marginalized groups. Other themes include witchcraft, Voodoo, racism, and family, such as the relationships between mothers and daughters. The season is set primarily in modern day and includes flashbacks to the 1830s.

Sadly, I’m afraid this new popularity will make my job more difficult-as we now have yet another layer of sensationalized and inaccurate portrayals of vodou/voodoo/voudou and witchcraft-wicca.

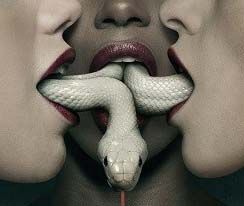

Angela Bassett as Marie Laveau

Bassett, who portrays Queen Marie, has been interviewed about her preparation for the role, and while I admire her acting, this gave me pause:

Bassett said she’s read Robert Tallant’s novel “The Voodoo Queen” and another nonfiction account of her famous character’s life, and has met with a couple of voodoo experts, one of whom is a practitioner. And she’s visited Laveau’s presumed tomb to investigate the rites that occur there.

Tallant’s novel, written in the 1940’s is a collection of racist, stereotyped, sensationalized hog-wash, replete with orgies and sacrificing of babies, which still sells well today, online and in tourist centers in New Orleans.

For serious scholarship on Queen Marie, and the lives of free women of color in that time period, I’d suggest several works:

The Mysterious Voodoo Queen, Marie Laveau: A Study of Powerful Leadership in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans, by Ina Johanna Fandrich

Ina Johanna Fandrich’s book is not a biography of New Orleans’ Voodoo icon Marie Laveau (1801-1881) per se, although it contains a wealth of carefully collected data about her. Rather, it explores Laveau’s significance as the quintessential figure within a larger movement: the emergence of influential free women of color, women conjurers of African or racially mixed origin with strong ties to the Roman Catholic Church and a deep commitment to the spirits of their ancestors, who had considerable influence over the city despite their marginalized social and religious status. The heyday of this movement coincided with Laveau’s lifetime.

A New Orleans Voudou Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau, by Carolyn Morrow Long

Against the backdrop of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century New Orleans, A New Orleans Voudou Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau disentangles the complex threads of the legend surrounding the famous Voudou priestess. According to mysterious, oft-told tales, Laveau was an extraordinary celebrity whose sorcery-fueled influence extended widely from slaves to upper-class whites. Some accounts claim that she led the “orgiastic” Voudou dances in Congo Square and on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, kept a gigantic snake named Zombi, and was the proprietress of an infamous house of assignation. Though legendary for an unusual combination of spiritual power, beauty, charisma, showmanship, intimidation, and shrewd business sense, she also was known for her kindness and charity, nursing yellow fever victims and ministering to condemned prisoners, and her devotion to the Roman Catholic Church. The true story of Marie Laveau, though considerably less flamboyant than the legend, is equally compelling.

In separating verifiable fact from semi-truths and complete fabrication, Long explores the unique social, political, and legal setting in which the lives of Marie Laveau’s African and European ancestors became intertwined. Changes in New Orleans engendered by French and Spanish rule, the Louisiana Purchase, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow segregation affected seven generations of Laveau’s family, from enslaved great-grandparents of pure African blood to great-grandchildren who were legally classified as white. Simultaneously, Long examines the evolution of New Orleans Voudou, which until recently has been ignored by scholars.

and for more historical context:

“Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century”, by Gwendolyn Midlo Hall

Although a number of important studies of American slavery have explored the formation of slave cultures in the English colonies, no book until now has undertaken a comprehensive assessment of the development of the distinctive Afro-Creole culture of colonial Louisiana. This culture, based upon a separate language community with its own folkloric, musical, religious, and historical traditions, was created by slaves brought directly from Africa to Louisiana before 1731. It still survives as the acknowledged cultural heritage of tens of thousands of people of all races in the southern part of the state. In this pathbreaking work, Gwendolyn Midlo Hall studies Louisiana’s creole slave community during the eighteenth century, focusing on the slaves’ African origins, the evolution of their own language and culture, and the role they played in the formation of the broader society, economy, and culture of the region. Hall bases her study on research in a wide range of archival sources in Louisiana, France, and Spain and employs several disciplines–history, anthropology, linguistics, and folklore–in her analysis. Among the topics she considers are the French slave trade from Africa to Louisiana, the ethnic origins of the slaves, and relations between African slaves and native Indians. She gives special consideration to race mixture between Africans, Indians, and whites; to the role of slaves in the Natchez Uprising of 1729; to slave unrest and conspiracies, including the Pointe Coupee conspiracies of 1791 and 1795; and to the development of communities of runaway slaves in the cypress swamps around New Orleans.

So who exactly was Marie Laveau? There are no photographs of her, and few descriptions, other than that she was light of skin-color and always wore a tignon. We know she worked as a hairdresser, and was a devout Catholic, and had a close association with Père Antoine, pastor of the Church of St. Louis.

Some researchers state “Marie was believed to have been born free in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, about 1794, the daughter of a white planter and a free Creole woman of color”. Others assert her father was a free man of color Charles Lauveaux.

On August 4, 1819, she married Jacques (or Santiago, in other records) Paris, a free person of color who had emigrated from Haiti. Their marriage certificate is preserved in St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans. The wedding Mass was performed by Father Antonio de Sedella, the Capuchin priest known as Pere Antoine.

Jacques Paris died in 1820 under unexplained circumstances. He was part of a large Haitian immigration to New Orleans in 1809 after the Haitian Revolution of 1804. New immigrants consisted of French-speaking white planters and thousands of slaves as well as free people of color. Those with African ancestry helped revive Voodoo and other African-based cultural practices in the New Orleans community, and the Creole of color community increased markedly.

After Paris’s death Marie Laveau became a hairdresser who catered to wealthy white families. She took a lover, Christophe (Louis Christophe Dumesnil de Glapion), with whom she lived until his death in 1835. They were reported to have had 15 children including Marie Laveau II, born c. 1827, who sometimes used the surname “Paris” after her mother’s first husband.

Very little is known with any certainty about the life of Marie Laveau. Her surviving daughter had the same name and is called Marie Laveau II by some historians. Scholars believe that the mother was more powerful while the daughter arranged more elaborate public events (including inviting attendees to St. John’s Eve rituals on Bayou St. John). They received varying amounts of financial support. It is not known which (if not both) had done more to establish the voodoo queen reputation

An interesting footnote to history, former White House social secretary Desirée Glapion Rogers, is a descendant of Marie Laveau.

In order to understand the role of a priestess in vodou, we have to be clear that Louisiana practice, and those of the Caribbean, South American versions derive from West Africa.

Vodun or Vudun (spirit in the Fon and Ewe languages, pronounced [vodṹ] with a nasal high-tone u; also spelled Vodon, Vodoun, Voudou, Voodoo etc.) is an indigenous organized religion of coastal West Africa from Ghana to Nigeria. Vodun is practised by the Ewe people of eastern and southern Ghana, and southern and central Togo, the Kabye people, Mina people and Fon people of southern and central Togo, southern and central Benin and (under a different name) the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria.It is distinct from the various traditional animistic religions in the interiors of these same countries and is the main origin for religions of similar name found among the African Diaspora in the New World such as Haitian Vodou, the Vudu of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, Candomblé Jejé in Brazil (which uses the term Vodum), Winti in Suriname (which is also syncretized with American Indian aspects), and Louisiana Voodoo. All these are syncretized with Christianity and the traditional religions of the Kongo people of Congo and Angola.

Louisiana Voodoo, is related to, but not the same as Hoodoo, conjure or root work, an amalgam of European and African diasporic folk magic beliefs and rituals.

Marie Laveau is one of the preeminent historical figures of that tradition, along with John Montenet, better known as Doctor John. Her purported tomb in the Saint Louis Cemetery has become a shrine, and major tourist attraction, where people leave offerings.

I hope that one day, an intrepid filmmaker will take on the task of portraying the complexity of Laveau, and the lives of people of color-free and enslaved in Louisiana from that time period. Until that time, I’m afraid we will get more of the same, a world of voodoo dolls stuck with pins (which is really a European folk magic tradition and not vodoun), and voodoo queens who bear little resemblance to historical reality.

Till then I’ll just listen to my old friend Dr. John’s rendition of her in song:

Cross-posted from Black Kos

10 comments