Solomon Northup

With all the movie talk centering around the film 12 Years a Slave, the plot, the cast, the director, critical reviews and audience responses, it is important that we don’t forget that this film is taken from real life…our history and yet, bound to our present.

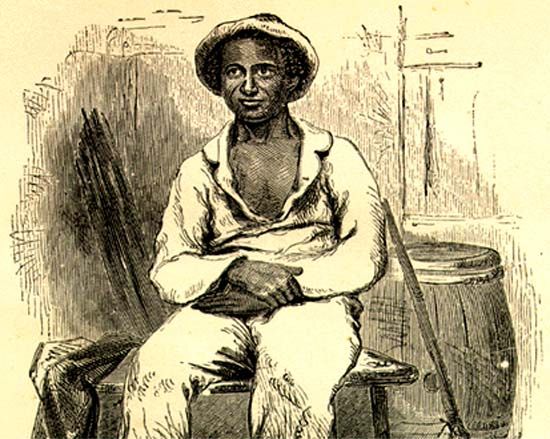

Solomon Northup’s tale is one of many narratives of the era of enslavement, and its aftermath.

I haven’t seen this film yet, years ago I saw the version directed by Gordon Parks, “Solomon Northup’s Odyssey, reissued as Half Slave, Half Free” and read Northup’s published narrative many years before then, several times.

Given my own interests in genealogy and history, reading his harrowing tale, and about his eventual escape, even though his fate in later years is buried in mystery, I thought about his wife, his children and his descendants.

It is good to see those who came after him gather in his name as a living legacy.

Descendants gather from across the country for 15th annual Solomon Northup Day

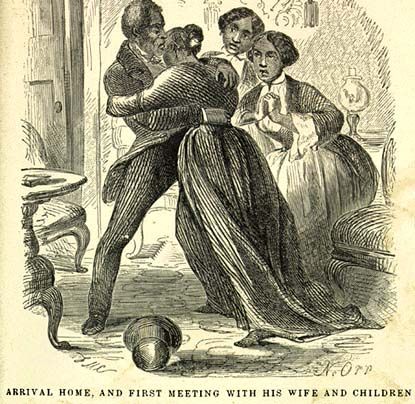

SARATOGA SPRINGS — The 12 years that Solomon Northup was a slave did not only affect the rest of his life.

Saturday at Skidmore College, more than 40 of his descendants traveled from all over the country to celebrate the 15th annual Solomon Northup Day, and many shared how he has impacted their lives.

“It’s like finding a missing piece of your life’s puzzle,” said Clayton Jamie Adams of Pittsburgh, the great-great-great-grandson of Solomon Northup on his mother’s side.

He said growing up he didn’t know about his legacy. In college, he remembers reading about Northup in a class on black literature, but even then was unaware of his connection to him.It wasn’t until talking to his grandmother, Victoria Northup, that he discovered that branch of his roots and “discovered the beautiful family history you can’t put on paper.”

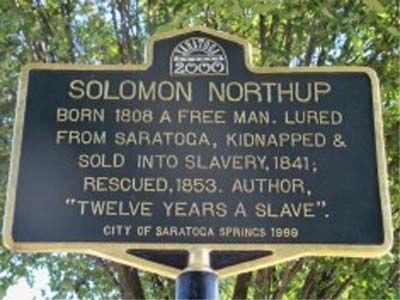

Through the efforts of Canadian, Samuel Bass, both black and white citizens of Saratoga, Hudson Falls (Sandy Hill) and Louisiana were instrumental in restoring his freedom in 1853. A literate man, Mr. Northup published his autobiography, entitled Twelve Years a Slave, in 1853(still in print and widely read).

Although Mr. Northup sought to bring his captors to trial, they were never prosecuted and he mysteriously disappeared. To date, his burial site has not been identified and it is not known whether or not he was killed, re-captured, or died of natural causes.

In 1999, in recognition of his life’s work, his ordeal and that of other African-Americans, native Saratogian, Renee Moore, founded “Solomon Northup Day – A Celebration of Freedom”. This historical and educational community event received recognition by the Library of Congress Bicentennial Local Legacies Project in 2000.

Former U.S. poet laureate Rita Dove wrote in her poem “The Abduction,” about “Solomon Northrup / from Saratoga Springs, free papers in my pocket, violin / under arm, my new friends Brown and Hamilton by my side” who, participating with his “friends” in a carnival act, “woke and found [himself] alone, in darkness and in chains.”

Those chains of enslavement shaped the United States as a nation. Many of us are direct descendents of those held in bondage. Others among us descend from those who were enslavers, or who profited from the triangle trade. Still others among us descend from fighters for abolition, or have ancestors who fought for the Union and the Confederacy. Later immigrants to the U.S. have moved into cities like New York, built with slave labor.

The very name “Wall Street” is born of slavery, with enslaved Africans building a wall in 1653 to protect Dutch settlers from Indian raids. This walkway and wooden fence, made up of pointed logs and running river to river, later was known as Wall Street, the home of world finance. Enslaved and free Africans were largely responsible for the construction of the early city, first by clearing land, then by building a fort, mills, bridges, stone houses, the first city hall, the docks, the city prison, Dutch and English churches, the city hospital and Fraunces Tavern. At the corner of Wall Street and Broadway, they helped erect Trinity Church.

On the west coast, Los Angeles was founded by blacks and native americans, with only 2 whites in the group of pobladores.

Our nation’s capitol was built on the backs of blacks.

Growing up on the stories of enslaved ancestors told by my parents and grandparents, and later in life diving into the history of slavery here, in the Caribbean and Latin America, I feel an intimate and visceral connection. I am not blind either to the inheritance of racism that still shapes the virulent hate we live with or to the systemic/economic inequity we still face, resulting from a history that is not long ago nor far away.

Too often I hear the plaint “slavery had nothing to do with me or my family” from those who came here far after its “official” death.

Not true. Even now, voices on the right respond to yet another film about enslavement, with scorn and whines of denial.

They reject the ties that still bind us all, our present to our past.

David Simon, wrote in his film review of “12 Years a Slave”:

Everyone who had anything to do with this film getting made – from the producers, to director Steve McQueen, and the committed, talented cast – should sleep tonight and every night knowing that for once, the escapism, bluster and simple provocation that marks a good 95 percent of our film output has been somehow flanked, and subversively so. These people have told a hideous and essential story about our nation’s great and longstanding sin with such calm and clarity that if we accept the film on its actual terms, rather than through the cluttered prism of our own racial and political sensibilities, only two kinds of folk will emerge from theaters.

The first will be at last awakened to the actual and grievous horror in which the black experience in America begins. Efforts to achieve this in the past – The “Roots” miniseries on television, or a few halting and veiled attempts in feature films to imply the desperation of terrorized human chattel – came down the road a piece, but none dared the entire emotional journey. For ordinary Americans willing to confront our history without equivocation and vague allusion, this film will prove a humanizing and liberating journey. This much truth can grow an honest soul.

And for those still desperate to mitigate our national reality at every possible cost, this film will be an affront. It is not intelligently assailable by anyone, though the racial divide and resentment that still occupies our national character a century and a half after abolition will prompt certain creatures to pull at threads, hoping against hope. Mostly, those who want to pretend to another American history will just avoid the film or the discussion that ensues.

The film’s website has a link to screening locations.

You can join the discussions on facebook.

Denying history denies our present, and limits our future.

Slavery isn’t just black history. It belongs to us all.

7 comments