Re-creation of burned Greyhound Freedom Rider bus, National Civil Rights Museum

The recreation of the burned out Greyhound bus pictured above doesn’t begin to capture the horror of the actual event, that took place on Mother’s Day outside of Anniston, Alabama.

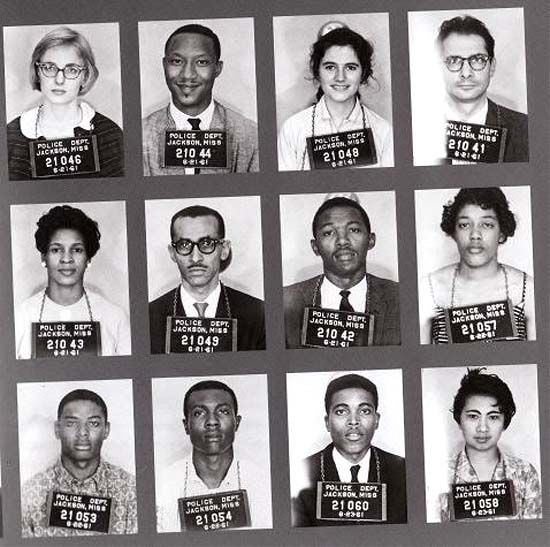

Perhaps this actual photo illustrates more of the tale that is told by those Freedom riders who were on the bus that day.

It is May. Springtime. A month of hope and rebirth. It is also a month of memories that we need to revisit yearly until the seeds of hate no longer can sow sorrow in the U.S.A.

I was only 13 years old in May of 1961. Not too young to be concerned with civil rights however, and I looked up to those young people, only a few years older than I, who packed up their bags and headed off to do battle against racial segregation.

They were black, and white, and they knew they were facing possible death.

Yet they got on buses and headed south.

The 50th anniversary of the Freedom rides and riders was held last year. This year it is 51. Before too long, none of the living will be around to tell their tales in person. But there are those of us who will not forget- ever.

Make sure you pass this recent (to me) history on to young folks. It is a lesson in courage. The courage of the young who wouldn’t listen to those, often wise leaders who discouraged them from making a journey. A journey that changed history.

For the 40th reunion David Lisker wrote this story.

“The Last Supper”

On May 4th, 1961 the night before they were to leave on the first Freedom Ride, the Freedom Riders and the architects of the Ride met. Present at the dinner were Dianne Nash, the striking young spokeswoman of the group who was considered too valuable a figure to go on the Rides herself and would instead coordinate efforts back in Nashville; and James Lawson, the mentor of the Freedom Riders’ in the art of non-violence.

At a Chinese restaurant in Washington, DC, John Lewis, a young man from rural Georgia and theology student at the American Baptist College in Nashville sat in awe at the scene before him, partly out of fear at what lay ahead for them all and partly for the fact that it was the first time in his life that had ever seen Chinese food. While he greatly enjoyed the evening’s meal that night, John Lewis (now a US Congressman from his home state of Georgia) would later liken it to “the last supper.” Other Freedom Riders in attendance that evening included Marion Barry, James Bevel, Hank Thomas, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, B. Elton Cox, Bernard Lafayette and Jim Zwerg.

The Freedom Rides Begin

The next morning the Freedom Rides boarded the buses and took their places, blacks and whites seated together on the bus, an act already considered a crime in most segregated states. At stops along the way, the Freedom Riders entered “whites” and “colored” areas contrary to where they were supposed to go and ate together at segregated lunch counters. They met little resistance along the way until Rockville, S.C. where an angry mob beat the Freedom Riders as they pulled into the station. This was the first of many such beatings the Freedom Riders were to receive at the hands of angry mobs.Undaunted by the beatings. the Freedom Riders continued on their journey until Mother’s Day, May, 14th, 1961 when they were met by an angry mob (dressed in their Sunday finest as if they’d just come from church) in Anniston, Alabama. Due to the ferocity of the mob, the bus decided not to stop at the station and it quickly left, already wounded by the mob who had slashed the bus’s tires at the station. A few miles outside of Anniston the tires began to deflate and the bus was forced to pull over. As the bus driver fled in glee, a mob of men who had been following the bus got out of their cars and surrounded the stricken bus. From somewhere in the crowd a firebomb was thrown inside the bus and exploded. As the Freedom Riders tried to escape the smoke and flames they found they could not as the exit doors were blocked by the surging mob. Just then one of the gas tanks exploded on the bus and the mob rushed back allowing the Freedom Riders to push the doors open and escape. As they exited the burning bus, the Freedom Riders rushed outside still choking from the thick smoke and were beaten by the waiting vigilantes. As lead pipes and baseball bats were swung, only an onboard undercover agent prevented the Freedom Riders from being lynched that day as he fired his gun into the air. Later that same day the Freedom Riders were beaten a second time as they arrived in Birmingham, Alabama.

This NPR story Get On the Bus: The Freedom Riders of 1961, gives more detail, excerpted from Raymond Arsenault’s book (featured below).

Flinging open the door, the driver, with Robinson trailing close behind, ran into the grocery store and began calling local garages in what turned out to be a futile effort to find replacement tires for the bus. In the meantime, the passengers were left vulnerable to a swarm of onrushing vigilantes. Cowling had just enough time to retrieve his revolver from the baggage compartment before the mob surrounded the bus. The first to reach the Greyhound was a teenage boy who smashed a crowbar through one of the side windows. While one group of men and boys rocked the bus in a vain attempt to turn the vehicle on its side, a second tried to enter through the front door. With gun in hand, Cowling stood in the doorway to block the intruders, but he soon retreated, locking the door behind him. For the next twenty minutes Chappell and other Klansmen pounded on the bus demanding that the Freedom Riders come out to take what was coming to them, but they stayed in their seats, even after the arrival of two highway patrolmen. When neither patrolman made any effort to disperse the crowd, Cowling, Sims, and the Riders decided to stay put.

Eventually, however, two members of the mob, Roger Couch and Cecil “Goober” Lewallyn, decided that they had waited long enough. After returning to his car, which was parked a few yards behind the disabled Greyhound, Lewallyn suddenly ran toward the bus and tossed a flaming bundle of rags through a broken window. Within seconds the bundle exploded, sending dark gray smoke throughout the bus. At first, Genevieve Hughes, seated only a few feet away from the explosion, thought the bomb-thrower was just trying to scare the Freedom Riders with a smoke bomb, but as the smoke got blacker and blacker and as flames began to engulf several of the upholstered seats, she realized that she and the other passengers were in serious trouble. Crouching down in the middle of the bus, she screamed out, “Is there any air up front?” When no one answered, she began to panic. “Oh, my God, they’re going to burn us up!” she yelled to the others, who were lost in a dense cloud of smoke. Making her way forward, she finally found an open window six rows from the front and thrust her head out, gasping for air. As she looked out, she saw the outstretched necks of Jimmy McDonald and Charlotte Devree, who had also found open windows. Seconds later, all three squeezed through the windows and dropped to the ground. Still choking from the smoke and fumes, they staggered across the street. Gazing back at the burning bus, they feared that the other passengers were still trapped inside, but they soon caught sight of several passengers who had escaped through the front door on the other side.

They were all lucky to be alive. Several members of the mob had pressed against the door screaming, “Burn them alive” and “Fry the goddamn niggers,” and the Freedom Riders had been all but doomed until an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode. As the frightened whites retreated, Cowling pried open the door, allowing the rest of the choking passengers to escape. When Hank Thomas, the first Rider to exit the front of the bus, crawled away from the doorway, a white man rushed toward him and asked, “Are you all okay?” Before Thomas could answer, the man’s concerned look turned into a sneer as he struck the astonished student in the head with a baseball bat. Thomas fell to the ground and was barely conscious as the rest of the exiting Riders spilled out onto the grass.

Yet even in the midst of this hatred there were a few who went against the tide. One was a 12 year old white girl, Janie McKinney.

When she was growing up, the KKK was so feared and accepted by the community that her father, a small-town grocer, felt pressured to join. “He used to say, ‘It’s good for bid-ness,'” McKinney recalled of her dad. “But he was a kind-hearted soul. If he found out people were hungry, he would give them food. He didn’t care what color they were.'”But racism was deeply embedded in Anniston and surrounding towns in the form of brutal, midnight beatings of black men “who didn’t remember their place” and white-only schools and restrooms. McKinney felt differently, largely because of Pearl Seymore, the family’s black housemaid who helped raise her and whom she loved. By age 12, McKinney was “old enough to know about the Klan … and I was deathly afraid of them. The Klan was like a nightmare. It was something you could see out of the corner of your eye, and then it would disappear.”

One day, her dad let her in on a secret: Outside agitators from up north were on their way by bus from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans and would be passing through town. But the KKK, he told her, was going to give them a little surprise party before they reached Anniston…

Young Janie would be not only an eye witness, but a participant that day.

Riding on its rims with sparks flying, the bus finally could go no farther and stopped next to McKinney’s home and adjacent grocery store. As the angry mob surrounded the bus, the white bus driver ran off. Watching, McKinney saw a hand with a crowbar or heavy chain emerge above the crowd and smash out the back window of the bus. In the next moment, someone threw an incendiary device through the broken window, instantly filling the bus with roiling black smoke.

Outside the grocery store, men gathered to watch. “The people on the bus were gagging,” she recalled. While some of the passengers lay down on the bus floor in search of air to breathe, others, including an elderly black woman, panicked. Meanwhile, the crowd yelled out epithets, McKinney recalled. “They were saying things like, ‘Roast those n*****s alive.'” There were reports of people outside the bus holding the bus doors shut to prevent anyone from escaping. Then, something in the bus exploded, forcing the mob back and giving the passengers a chance to break out of the burning vehicle. “The door burst open, and there were people just spilling out of there. They were so sick by then they were crawling and puking and rasping for water. They could hardly talk.” Those desperate voices, raw with smoke, propelled McKinney to do something. The 7th grader ran into the house, washed out a bucket, filled it with water, grabbed some cups and went into the crowd. “I couldn’t just stand there and do nothing,” she said.

The first person she helped was the elderly black woman, who reminded her of Pearl. “Thank God Pearl wasn’t there that day,” McKinney said. “She didn’t have to see this.” After giving her water and washing her face, the girl then went on to give water to others. Chaos erupted as the crowd closed in on the Freedom Riders, some of whom were beaten as they scrambled off the burning bus. “I don’t know why they let me live. I figured, well, maybe they won’t kill me because I’m not grown up yet. If I had been, they would have had my head on a pike.” But she felt she had to live up to her Christian beliefs, she said, summed up in “Whatever you do to the least of my brothers, you do to me.”

Bless you Janie.

I have always found it ironic, that those very same people who hate us, want to segregate us, and yes…sometimes kill us, turn their children over to us to raise.

I re-watched Stanley Nelson’s documentary film, Freedom Riders, produced for PBS this morning.

You can view it in its entirety online.

The trailer:

I encourage you to watch the whole film.

And to read the book which inspired it.

Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, by Raymond Arsenault.

You should also read Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders , by Eric Etheridge, whose website documents many of those who got on the bus, and supported the movement.

Democracy Now covered the history, the anniversary and the film.

It is May again.

And I am remembering. Thankful for what young people risked for all of us.

But as the clouds of racial hatred still loom to block the sun of a new day, we should not just remember. We should move forward, take action, and be clear that the civil rights won in the past are being threatened today. The future is not yet written.

It’s up to all of us to write it together.

Cross-posted from Black Kos

21 comments