Some of the largest cataclysmic geologic events on earth occurred in what is now the Pacific North West. About 11 million years of volcanic flow activity, ending about 6 million years ago, created the Columbia Plateau with basaltic lava formations up to two miles deep. This huge basaltic plateau covering much of Eastern Washington and Oregon and adjacent parts of Idaho was later inundated by massive Ice Age floods ending about 15,000 calendar years ago. The scale of these events has been seldom seen elsewhere as it carved a landscape that appears other worldly. (In fact, the resulting terrain so closely matches that seen on Mars that NASA tested the Sojourner robotic rover here before its 1997 mission to Mars.

Scablands from basalt and flooding

The Columbia River continues to cut into basalt

As many as 100 floods deposited layers of sediment atop the basalt that today provide the soil for growing some of the best wine grapes and hence wines in the country and in some cases, the world. These are the wines of Oregon and Washington State.

I will review briefly the floods, how they formed this area and laid the ground work for today’s wine grape growing Mecca in eastern Washington State. I will focus on geology and vineyards of the Walla Walla Valley as they are not only as good as they get but also illustrate the various geologic processes that contribute to the unique terroir of the region. Further, this is where I recently participated in a field trip exploring the geology of the Walla Walla Valley’s terroir. One of the leaders of this field trip, Dr. Kevin Pogue was just featured in the New York Times’ Dining Section describing the wines and terroir of the region.

Terroir is a French word, initially denoting a geographic area but in relation to wine it also includes all of the unique physical characteristics of the area that contribute to the distinct qualities of the grapes and hence their wines. These characteristics might include mineral content of the soil, the diurnal temperatures, angle of the slope relative to the sun, wind, and rain fall among others. Also illustrative of the favorable conditions of this area is that it lies at a mean latitude of North 46 degrees, identical to the prime red wine growing regions of France. In short, terroir connotes all the characteristics that differentiate one piece of land from another. The Walla Walla Valley, including its adjacent lands in Oregon, contains some 120 wineries and 12 distinct American Viticultural Areas (AVA), each with its own terroir. Ninety nine percent of the grapes grown in Washington State are from the Columbia Plateau and 90% are from land directly affected by the flood deposits.

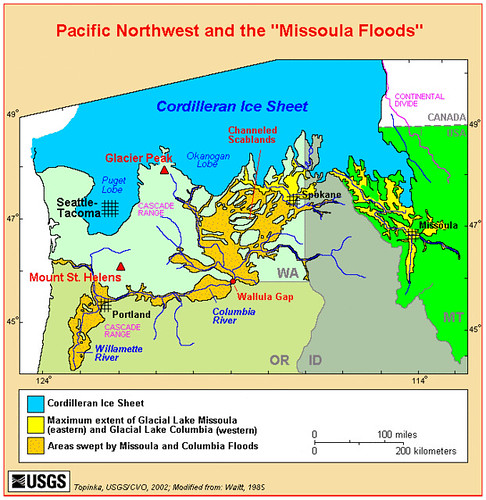

The Pleistocene Epoch spanning the time period of approximately 2.6 million to 11,000 years ago, is marked as a series of Ice Ages with alternating cooling and warming cycles. Over the last 1 million years, an ice age occurred on an average of one every 100,000 years. With each successive cooling, huge continental glaciers or ice sheets extended down into the northern tier of the Continental US. As lobes of this Cordilleran ice sheet (see map below) moved south they blocked stream and river drainages causing huge lakes, the largest of which was the Glacial Lake Missoula in north western Montana.

Another Glacial Lake, Lake Columbia formed in north Central Washington State and ultimately emptied down the Columbia River valley. With successive warming cycles the ice dams failed, sending huge floods down the Columbia River drainage basin. The largest of these floods flowed at a rate greater than all of the world’s rivers combined and drained to the Pacific Ocean for up to a week or so at a time. These tumultuous flows carved huge channels into the basalt floor across central Washington creating Coulees (e.g. Grand Coulee Dam) and scablands. See Hugefloods.com for great coverage of these events.

The only outlet for the water to run to the ocean was the Columbia River drainage that had a number of carved gaps that ultimately restricted flow. The major restriction was through Wallula Gap seen at the beginning of this diary and is now a National Natural Landmark.

This gap that now rises about 1,000 feet above the Columbia River was not large enough to handle all the water at once. (see first photo) The flood waters backed up to fill temporary Lake Lewis until it too could flow to the sea. Lake Lewis backed up, about 80 miles west to Yakima, and 30 miles east up the Walla Walla river Valley. Today McNary Dam backs up the river through the gap and is called Lake Wallula.

Further down the Columbia on the journey to the sea, other bottle necks occurred such as around Kalama Washington where temporary Lake Allison flooded the Willamette valley which is Oregon’s primary wine grape growing region.

While these waters of Lake Lewis slowed and waited their turn to flow west, they deposited a great deal of the sediment that it had stirred up from its roiling journey down the Columbia River drainage. This sediment is visible today in numerous layers of fine grained sand and silt deposited by successive floods over perhaps a million years. With winds from the southwest, some of this sediment formed dunes of sand and loess deposits (the silty sediment) distributed to the north and east. These deposits are the foundation for the rich farm land of Eastern Washington, and of course some of the terroir.

Sedimentary layers along the Columbia at White Bluffs

Each successive flood left a layer of its sediments called a rhythmite with heavier grains of sand on the bottom and finer grained silt on top. These layers once filled the entire valley but have since been eroded by the Walla Walla River wending from the Blue Mountains to the east to its confluence with the Columbia River at Wallula Gap in the west. The consecutive layers of silt are readily seen from road cuts through hills along the valley floor. Also visible in the road cuts are layers of white volcanic ash deposited from an eruption of Mt. St. Helens about 15,000 years ago.

Sedimentary rhythmites at Burlingame Canyon

One of the best illustrations of these rhythmite layers came from an inadvertent event near Walla Walla in the 1920s when a breached irrigation ditch released an eroding torrent of water for about a week. That torrent carved deep into the past showing up to 40 layers of sediment and therefore implies the return of numerous flood events. The carved out layers are shown above as the Burlingame Canyon.

The Vineyards:

Grape growing in The Walla Walla Valley is a relatively recent undertaking. Gary Figgins, owner of Leonetti vineyards planted the first commercial wine grapes here on his grandparents’ property in 1974. From this beginning, nearly 40 years later there are some 1,600 acres of vineyards and more than 120 wineries in this valley taking advantage of its unique terroir.

Leonetti’s Cellers vinyeard

Terroir from the mountains, foothills, to the valley floor.

Loess and caliche layers in Walla Walla Valley

Some vineyards are planted well above the layered sediment on the valley floor but yet take advantage of that sediment. These vineyards are planted on the loess, which are windblown deposits of the sediment that themselves layered the hills above and beyond the flooding. Among the most prestigious of these loess vineyards is Seven Hills which has produced numerous award-winning wines by vintners such as Leonetti Cellars, L’Ecole 41, Woodward Canyon,Seven Hills. These are red grape growing areas producing Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Sangoivese, and some Viognier for blending into Rhone-Style wines.

Another vineyard that takes special advantage of the geology and local terroir of the Walla Walla Valley is Cayuse Vineyards, owned by a transplanted French vintner, Christophe Baron. While surveying the area, he noted that a field of basalt cobbles brought out of the Blue Mountains by the Walla Walla River was reminiscent of the stones, including their taste on licking, that littered the Southern Rhone Valley in France. The winery’s name, Cayuse stems from this experience. Early 19th Century French-Canadian fur trappers, probably working for Hudson’s Bay, had dubbed the local Indian tribe the Cayuse. Cayuse was a derivative of the French word for stones, cailloux.

Cayuse Vineyard with cobbles

Cayuse vineyards draw on these basalt cobbles, loess, and flood sediments that account for his unique, highly prized, and sought after Rhone-style wines. (It takes about 8 years on his mailing list before you can actually get to buy these wines.) In addition to the nutrient values of the soils, the stones are raked up around the plants to collect and retain heat from the sun that further complements the vine and grape development. Further, Baron has restarted an age old practice of having all the tilling of his newest vineyard done by two Belgium draft horses named “Zeppo” and “Red” in what he calls his “Horse-Power” vineyard. Baron is the first vintner in Washington State to implement bio-dynamic farming using chemical free methods.

Cayuse’s Horse Power Vineyard

Other consequences of the Ice Age Floods.

Buried mammoths:

In addition to contributing to the terroir for grapes, other consequences of these catastrophic Ice Age floods included that untold numbers of Columbian mammoths were swept up in the flash flood turbulence and their remains deposited in the slackwater sediments of Lake Lewis.

One mammoth dig currently underway in the Horse Heaven Hills just south of Kennewick, is called the Coyote Canyon Mammoth site. The remains found at this site have been carbon dated to approximately 17,500 calendar years ago which is within the time frame of some of the latter floods. Paleontology studies such as this can further elucidate the flora and fauna that inhabited this plateau over the past several thousand years.

Erratics

Also buried throughout the flood region are large isolated granite boulders not otherwise found in this part of the country and therefore called “erratics.” During the ice age floods these boulders were caught up in the huge glacial ice flows originating in what is now Canada and carried south into Washington, Idaho, and Montana. With the floods, they were rafted hundreds of miles in ice bergs until they melted and were deposited randomly along the flood routes. Given the size of some of these erratics, one can only imagine the tremendous power of the floods’ currents.

The Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail

Gary Kleinknecht, Pres. IAFI, Rep. Doc Hastings,

& Sen. Maria Cantwell dedicating the Trail.

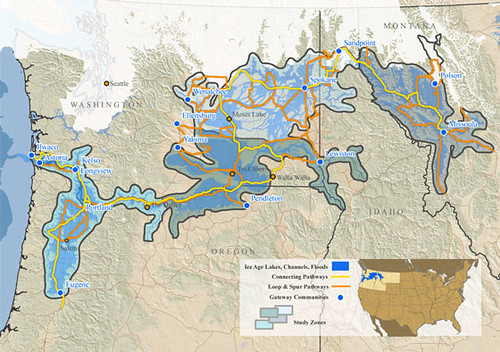

The Ice Age Floods Trail was established by the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, in which Congress authorized establishing the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail in parts of Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon states, and established National Parks Service administration of the Trail.

For those readers living in this part of the world, and for all of those interested in geology and/or wines, who might want to visit, a trip over the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail would be well worth your time. The occasional stop along the trail for sampling wines in Washington and Oregon would only add to your trip in terms of its educational, culinary, and enological pleasures.

References:

Bjornstad, B.N., (2006) On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods, A Guide to the Mid-Columbia Basin, Keokee Books, Sandpoint Idaho.

Carson, R. (ed.) ( 2008) Where the Great River Bends: A Natural and Human History of the Columbia at Wallula.Keokee Books, Sandpoint Idaho

Last, G., Barton, B., & Kleinknecht, G. (2013). “Preliminary Paleontology and Geology of the Coyote Canyon Mammoth Site, Benton County Washington.” The Pleistocene Post, Newsletter of the Ice Age Floods Institute, Spring 2013.

Pogue, K., Urban, R., Last, G., & Bjornstad, B. ( April, 20, 2013): Ice-Age Floods and the Terroir of the Walla Walla Valley. (a Field guide.)

Thanks for the history and consultation goes to Gary Kleinknecht, George Last, Bruce Bjornstad, and Kevin Pogue for leading the field trip through this amazing historic area. Accuracy of dates and details rests solely with the author.

8 comments