Rev. Ben Chavis, Joe Wright, Connie Tindall,

Jerry Jacobs; from left, back row, Wayne Moore,

Anne Sheppard, James McKoy, Willie Vereen, Marvin Patrick and Reginald Epps. 1976

40 years to Justice: the Wilmington 10

It’s hard to believe that 40 years have passed since the conviction of the Wilmington 10, in 1972 for trumped up charges relating to a firebombing in the city of Wilmington in 1971. At the time I was editing the newspaper for the Black Panther Party Revolutionary People’s Communication Network, and we not only covered the trial and convictions, but corresponded with Ben Chavis, the alleged leader of the “conspiracy” while he was in jail.

Chavis was assigned to Wilmington, North Carolina in 1971 from the Commission for Racial Justice to help desegregate the public school system. Since the city abruptly closed the black high school, laid off its principal and most of its teachers, and distributed the students to other schools, there had been conflicts with white students. The administration did not hear their grievances, and the students organized a boycott in protest.

He and nine others were arrested in February 1971 for a firebombing, charged with conspiracy and arson, and convicted in 1972. The oldest man at age 24, Chavis drew the longest sentence, 34 years. The ten were incarcerated while supporters pursued appeals. The case of the Wilmington Ten received international condemnation as a political prosecution. In December 1980, the Federal Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered a new trial and overturned the original conviction.

In 1978 Amnesty International described Benjamin Chavis and seven others of the Wilmington Ten still in prison as “American political prisoners” under the definition of the Universal Rights of Man. They were prisoners of conscience. From this experience Benjamin Chavis wrote two books: An American Political Prisoner Appeals for Human Rights (while still in prison) and Psalms from Prison. In 1978, Chavis was named as one of the first winners of the Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award.

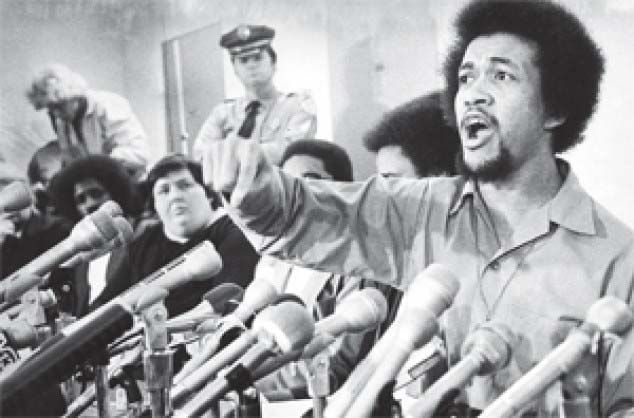

1978: Ben Chavis, right, speaking at a news conference

the day after Gov. Jim Hunt’s decision to reduce the sentences of the Wilmington Ten.

Hunt refused to pardon the group.

Background on the the trial and appeals

At the time, the state’s case against the Wilmington Ten was seen as controversial both in the state of North Carolina and in the United States. One witness testified that he was given a minibike in exchange for his testimony against the group. Another witness, Allen Hall, had a history of mental illness and had to be removed from the courthouse after recanting on the stand under cross examination.The group were convicted of the charges. The men’s sentences ranged from 29 years to 34 years for arson, severe proscription for a fire in which no one died.[1] Ann Shepard of Auburn, New York, age 35, received 15 years as an accessory before the fact and conspiracy to assault emergency personnel. The youngest of the group, Earl Vereen, was 18 years old at the time of his sentencing. Reverend Chavis was the oldest of the men at age 24. The sentences totaled 282 years.

Several national magazines, including Time, Newsweek, Sepia and The New York Times Magazine, published articles in the late 1970s on the trial and its aftermath. When then President Jimmy Carter admonished the Soviet Union in 1978 for holding political prisoners, the Soviets cited the Wilmington Ten as an example of American political imprisonment. Amnesty International (AI) took on the Wilmington Ten case in 1976. They classified the eight men still in prison as among 11 black men incarcerated in the U.S. who were considered to be political prisoners, under the definition in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 1976 and 1977, three key prosecution witnesses recanted their testimony.

In 1977 60 Minutes aired a special about the case, suggesting that the evidence against the Wilmington Ten was fabricated. In 1978, the New York Times reporter Wayne King published an investigatory article; based on testimony of a witness whose anonymity he protected, he said that perhaps the prosecution had framed a guilty man, as his source said that he had committed the crimes at the behest of Chavis. In 1980, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, a federal court, overturned the convictions, as it determined that (1) the prosecutor failed to disclose exculpatory evidence, in violation of the defendants’ due process rights [the Brady rule]; and (2) the trial judge erred by limiting the cross-examination of key prosecution witnesses about special treatment the witnesses received in connection with their testimony, in violation of the defendants’ 6th Amendment right to confront the witnesses against them. Chavis v. State of North Carolina, 637 F.2d 213 (4th Cir. 1980).

Though there is joy in North Carolina, and around the world, Jerry Jacobs, Ann Shepard, Connie Tindall and Joe Wright did not live to receive the pardons that were granted by outgoing Democratic Governor Bev Perdue. Life was not easy for those who not only did time, but then had to face a world where they were now “convicted felons.”

When Gov. Perdue issued the pardons she stated

“I have decided to grant these pardons because the more facts I have learned about the Wilmington Ten, the more appalled I have become about the manner in which their convictions were obtained,” Perdue, a Democrat who leaves office on Jan. 5, said Dec. 31.“Justice demands that this stain finally be removed. The process in which this case was tried was fundamentally flawed. Therefore, as governor, I am issuing these pardons of innocence to right this longstanding wrong.”

She said in a statement: “This conduct is disgraceful. It is utterly incompatible with basic notions of fairness, and with every ideal that North Carolina holds dear. The legitimacy of our criminal justice system hinges on it operating in a fair and equitable manner, with justice being dispensed based on innocence or guilt – not based on race or other forms of prejudice.”

She continued, “These convictions were tainted by naked racism and represent an ugly stain on North Carolina’s criminal justice system that cannot be allowed to stand any longer.”

Key in all of this, which pushed Perdue to issue the pardons were the people behind the Wilmington Ten Pardons of Innocence Project. They collected 0ver 144,000 petition signatures, they pushed the story to national media, and most importantly they had the backing of publisher Mary Thatch of the Wilmington Journal, the areas oldest black newspaper, and reporter Cash Michaels

Rallies were held across the state like this one, led by Rev. Barber, head of the NC NAACP:

Historian and Professor Tim Tyson, who was writing a book about the Wilmington 10 got his hands on Prosecutor Jay Stroud’s jury selection notes.

Ben David, the district attorney in New Hanover County, home of Wilmington, would not comment on the notes presented by the NAACP, other than saying that a few years ago he gave a box to a historian marked “Wilmington 10” that contained newspaper clippings and notes. David said he didn’t go through the box, which was in a closet.

“This file belongs not just to the DA’s office but to history,” David said. “And I shared that file with a historian.”

What was found in that box was key.

Wilmington 10 prosecutor sought ‘KKK’ jury, by Cash Michaels of The Wilmington Journal

The explosive “Stroud files,” as they’re being referred to, were discovered several months ago by a Duke University professor who was researching the Wilmington Ten case for a book he was writing. When the Wilmington Ten Pardons of Innocence Project, a special outreach effort of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) to seek pardons of innocence for the Ten from North Carolina Gov. Beverly Perdue, announced its formation earlier this year, the professor allowed the Wilmington Journal and Carolinian newspapers, both NNPA members, access to the materials.

Some of the contents of the Stroud files are being revealed only now because attorney Irving Joyner, law professor at North Carolina Central University School of Law in Durham, NC; and attorney James Ferguson of Charlotte, the original lead defense lawyer for the Wilmington Ten, spent the summer confirming the authenticity of the materials. On Sept. 5 during a forum at the law school on the Wilmington Ten case hosted by Professor Joyner; Rev. Chavis; Rev. Kojo Nantambu, a colleague who worked with Rev. Chavis in Wilmington in 1971 as they led a Black student boycott of the local racially divisive public school system; and Ms. Judy Mack, the daughter of now-deceased Wilmington ten member Anne Sheppard, attorney Ferguson confirmed what he discovered in the Stroud files.

This video shows the actual files with explanations:

There was a fair amount of confirmation of things we suspected at the time that race was the central strategy of the prosecution,” attorney Ferguson maintained, singling out a legal pad that prosecutor Stroud used during jury selection of the first trial to track Ferguson’s questioning of potential jurors in Pender County, a neighboring county the case had been moved to in June 1972. Pender had a larger African-American population than New Hanover, where the Wilmington Ten had been charged, thus, more Black candidates for jury service. Ferguson details how Stroud wrote on the top of one page of his jury selection legal pad “Stay away from Black men.” Next to that on the top of that same sheet, Stroud wrote, “Leave off Rocky [Point], Maple Hill. Put on Burgaw, Long Creek Atkinson Blacks.” Apparently in Stroud’s mind, Blacks from the more rural towns of Burgaw, Long Creek and Atkinson, would probably be less likely to identify with “radical” civil rights leaders like Ben Chavis than African-Americans from the more urbane towns of Rocky Point and Maple Hill. Indeed, the 29th prospective juror on that same page named “Randolph” has a capital “B” in front of his name in the margin, and in parentheses the word “no,” and written afterwards, “on basis Maple Hill.”

In contrast, another possible juror, number 9 with a “B” named “Murphy,” Stroud has written in parentheses, “Worth chance because from Atkinson.” There are several prospective jurors listed by name, and if not, certainly by number, who have the capital letter “B” written in the margin. If there was any doubt about the “B” indicating “Black” – which was attached to many names the words “leave off” were added. On prospective “B” juror number eleven named “Graham,” Stroud writes, “knows; sensible; Uncle Tom type.”

On Number 27 named “Stringfield,” Stroud writes, “no named Black on jury.” On Number 19 named “James” Stroud writes, “stay away from,” apparently indicating that the potential juror is a Black male he doesn’t want. And prosecutor Stroud had unmistakable codes for White jurors he preferred. On that same legal pad sheet tracking juror interviews, when Stroud was impressed with a White interviewee’s answers, he’d write down the three letters of the alphabet most commonly associated with the most fear White supremacist group in the South at the time – the Ku Klux Klan.

“KKK?…good” is what Stroud wrote for juror Number 1 known as “Pridgen.” For Number 6 named “Heath,” the reverse, “O.K.” then “KKK?”. Number 75 on a subsequent page was “Fine – probably KKK!!” and on Number 99 Stroud writes, “does not have a record – KKK!!” There are other potential White jurors Stroud has also written “KKK” next to, but he then crosses them out, possibly indicating that they were no longer eligible.

In some cases, Stroud apparently had trouble telling the difference between Whites and fair-skinned Blacks. For Number 38, the prosecutor writes, “good name and location – KKK if White.” On Number 59, Stroud writes, “take off on basis of name if Black.”

After studying the notes, Attorney Ferguson observed: “Race infused the jury selection strategy in that June trial.” When the first jury was dominated by Blacks, Ferguson said,

Since the embed code won’t work here please take a moment to listen to the NAACP press conference , led by Rev. Dr. William Barber, NC NAACP.

Ben Chavis makes a statement thanking Gov. Perdue on behalf of the Wilmington 10, declaring the pardons a victory for the civil rights movement.

Though most people know Rev. Ben Chavis from the time he headed the NAACP, many are not aware that he coined the term “environmental racism”

“Racial discrimination in the deliberated targeting of ethnic and minority communities for exposure to toxic and hazardous waste sites and facilities, coupled with the systematic exclusion of minorities in environmental policy making, enf

orcement, and remediation.” To prove the validity of his definition, Chavis in 1986 conducted and published the landmark national study: Toxic Waste and Race in the United States of America, that statistically revealed the direct correlation between race and the location of toxic waste throughout the United States. Chavis is considered by many environmental grassroots activists to be the “father of the post-modern environmental justice movement” that has steadily grown throughout the nation and world since the early 1980s.

To get a deeper sense of racial history, in the area, and events that drove Ben Chavis and others, we need to look at Killing of Henry Marrow, which is detailed in Professor Timothy Tyson’s book Blood Done Sign My Name

The book deals with the 1970 killing of Henry Marrow, a black man. This case helped galvanize the African-American civil rights movement in Oxford, North Carolina, where the book takes place, and across the eastern North Carolina black belt. It helped establish local civil rights activist Ben Chavis’ leadership in the black civil rights movement, which eventually led to his becoming the executive director of the NAACP and later an organizer of the Million Man March. This episode radicalized the African American freedom struggle in North Carolina, leading up to the turbulence of the Wilmington Ten cases, which grew out of racial conflict in the port city and the trial of Ben Chavis and nine others on charges stemming from the burning of a grocery store.

Tyson, whose father was the minister of the First United Methodist Church-Oxford, a prominent local church, explores not only the white supremacy of the South’s racial caste system but his own and his family’s white supremacy. He interweaves a narrative of the story and its effects on him with discussion of the racial history of the United States, focusing on the persistence of discrimination despite federal law and on the violent realities of that history on both sides of the color line. Tyson challenges the popular memory of the movement as a nonviolent call on America’s conscience led by Martin Luther King. The vision of the movement in these pages is local as well as national and international, violent as well as nonviolent, and far more complicated and human than the myth of “pure good versus bare-fanged evil in the streets of Birmingham,” as he puts it. Oxford writer Thad Stem, Jr. is a key figure in the book.

The book was made into a docudrama by the same name in 2010:

Directed by Jeb Stuart, Blood Done Sign My Name is an epic civil rights drama based on the acclaimed book of the same name by prize-winning author and fellow African American studies scholar, Timothy Tyson. Part autobiography, part history of the civil rights movement in the South, it recounts the murder of Henry Marrow, a 23 year-old black Vietnam veteran who was shot and beaten to death by a prominent white businessman and his grown sons. It also chronicles the reaction to Morrows killing by his cousin, Ben Chavis, who organized a peaceful, fifty-mile march to the states capitol, as well as a ten year old Tyson, who watched as his father, the pastor of the all-white Methodist church, tried to get his congregation to accept the inevitability of integration.

I’m always amazed when people refer to the Civil Rights Movement in America as if it was in the past – and ended. So many chapters of the struggle are still open, and until we defeat racism and get justice, the book will not be closed.

For slide shows, videos and more information, on the Wilmington 10, check out Triumphant Warriors.

(cross-posted from Black Kos Tuesday’s Chile)

63 comments