Following on from Mr Blask’s excellent ruminations on population growth and Sci Fi dystopias it failed to deliver, forgive me if I busk for a moment on another Sci Fi theme; partly as a rehearsal for a brief talk today for a Futureworld Event at London’s Science Museum Dana Centre.

To show how seriously I take this subject, I’m going to kick the talk off with a British ad from the 1970s for a synthetic mashed potato product.

What I love about this ad some thirty years on is that it touches so many of the science fiction elements of robotics, alien life, technology, imagined futures and mashed potatoes. But the three things I want to focus on in this brief talk are these:

1. What would it mean if robots could laugh?

2. Are we clearly ‘a most primitive people’?

3. How quickly does science fiction become historical fiction?

The last point first:

How quickly does science fiction become historical fiction?

Well, if the Smash ad is anything to go by, science fiction becomes historical fiction very fast, in fact faster than the Hamlet cigar or Yellow Pages ads from the same era. The idea that we would substitute a bland additive filled dried foodstuff with the nutritional value and texture of cardboard for real fresh root vegetables is a very outdated concept – perhaps one that lasted a decade or so.

But most the classic works of Science Fiction, from Jules Verne to Philip K Dick actually tell you much more about the eras they were imagined in that the futures they purported to imagine.

Two quick instances of this. Though Orwell’s 1984 remains a compelling portrait of a totalitarian state, with its doublethink and newspeak, the mood and the details of his dystopian epic are much more informed by 1948 than 1984 – which of course was Orwell’s intention.

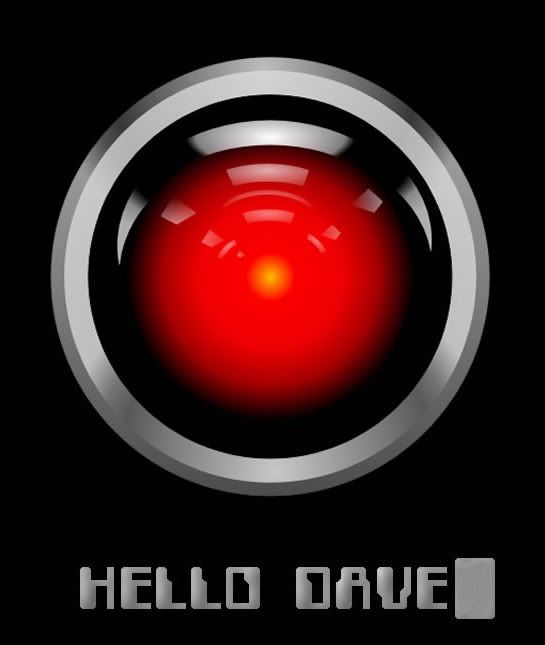

Similarly, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey tells us much more about the 1960s than anything else, with its sub-Darwinian emphasis on tool making and technology as the origin of humankind’s specialness and isolation. Take the name of the computer HAL, which suddenly gains intelligence and its own murderous intent when it murders one of the astronauts on the way to Jupiter. Of course HAL is a transposition of the letters IBM, and Kubrick projects into the future the massive centralised mainframes of the 60s than actually what happened in 2001, the era of the millions of small personal computers.

Again, the imagined futures of science fiction tell you more about the past than the future.

Are we clearly ‘a most primitive people’?

On this I think the Smash Robots are right. Even in our wildest science fiction myths we remain obsessed by the concerns expressed in primitive art, myth and legend. Science Fiction is theology by the back door, obsessed by optimism or pessimism, encounters with supernatural being which are either benevolent and benign, like ET or the extraterrestrials in the movie Contact, or malign, virulent and virtually indestructible, as in the War of the Worlds, The Thing or the alien in the Alien movies.

But it’s not all derivative. Though there are hints of the problem of human creativity in Hebrew myth of Adam and Eve plundering the Tree of Knowledge, or the Hellenistic story of Prometheus stealing fire from the Gods, Science Fiction is fixated on the problem of human creativity and invention: what happens when creatures become creators.

This is the recurrent strand from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein all the way to Blade Runner: what if our own creations run riot?

You can see this theme in many of the classic sci fi movies of late twentieth century – the machines taking over the world in the Terminator trilogy, a Skynet like mechanism using human beings as batteries in the Matrix.

In this way, the concerns revealed in Science Fiction show us to be still be wonderfully ‘primitive’, half fearing, half desiring some force bigger than ourselves, to defeat the world, to defeat, transform and reveal our humanity.

So finally….

What would it mean if robots could laugh?

It would be a lot. In fact it would mean that finally humans had managed to transcend themselves, to replicate themselves in inorganic matter, free from the biological inevitability of ageing, cell apoptosis and death. But I really don’t think this is going to happen anytime soon, despite the strongest wish fulfilment dreams of SciFi writers for the last century or more.

Artificial intelligence still looks pretty dumb to me. I still haven’t seen a robot that could beat us at football, let alone take over the world. However, belief in this inevitability is still current today among many thinkers, above all Raymond Kurzweil’s prediction of the transhuman melding of humanity and spiritual machines sometime in the next 50 years.

I love Kurzweil’s work, but I’m convinced his projections will, in the future, tell people more about our present than theirs. Until robots can laugh, or a computer can pass a proper Turing test, and tell you whether “Yes, dress looks good on you”, or “No I don’t think your wife still loves you”, I won’t believe the more breathless prognostications of mind machine melding or human surrender to hi tech.

Throughout its history, Sci Fi fantasies perversely succeed not because they are accurate about science or technology, but because by revealing the limits of both, they still keep talking to us about our rather primitive human nature, in all its inimitable comedy and pathos.

15 comments