A look at a memorable May, 1968 night in Boston – and the three men whose actions forty-six years ago helped that city avert a night of violence that afflicted many other US cities, after the jump ………….

Those of-a-certain-age may well recall the night of April 4th, 1968 …. when Dr. Martin Luther King was shot and killed in Memphis. Indeed, last year I visited the site of the Lorraine Motel, which is now the National Civil Rights Museum – and standing on the balcony outside Room #306 was a moving experience (which I noted in a previous essay).

Though as a twelve year-old, it couldn’t register on me the way it could had I been an adult: I certainly recall seeing TV images of riots and burning in major cities across the USA. It began that same night (when Bobby Kennedy made his plea for calm in Indianapolis) and Boston was no different than many other cities, as its African-American neighborhoods saw violence that night, as word of the killing began to emerge.

The next night (April 5th) promised to be even worse: as news of the assassination (in those pre-social media days) spread much more widely than the night it happened … and so even more areas fell under siege. The same fate may well have befallen the city of Boston, as a scheduled concert by James Brown that evening at the Boston Garden was initially threatened with cancellation by arena officials, worried about violence spreading to downtown.

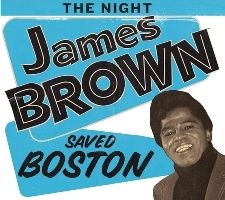

However, the fact that not only was the violence that afflicted other cities averted – but wound up being a night of less crime than normal in Boston – was a testament to the actions of three men. Not undeservedly, a VH-1 documentary film of the event was entitled The Night James Brown Saved Boston – but this could not have happened without two elected officials: a thirty-eight year-old rookie mayor, and a twenty-nine year old city councilman, whose story is not well-known and deserves to be told …………

The day after the assassination – who had gotten wind that the Garden was eager to cancel the concert – both the show’s promoter and the city’s lone African-American city councilman prevailed upon the city’s mayor not to cancel the concert … but add a novel twist. By cancelling the concert, ticket-goers would travel to a non-existent concert …. and possibly take out their anger downtown, rather than in their own neighborhoods (which the city’s white establishment feared most). Instead, why not prevail upon the city’s public TV station (WGBH) to televise the concert live – and then re-run it (twice) afterwards, for the benefit of those who learned of it late – as a way of keeping people indoors, where they could (it was hoped) hear a message of peace from the stage?

The mayor agreed and – with some arm-twisting and promises of restitution (both for lost ticket sales and for a broken contractual agreement not to appear on TV), James Brown agreed. WGBH is today a flagship public television station – with many locally-produced programs for national PBS viewers, including music – but back then, they were rather awkward at presenting music programs (especially with only a few hours notice). Indeed, they announced the show as “Negro singer Jimmy Brown and his band” – but they sensed the urgency, and agreed to carry the show.

James Brown is legendary, whose story will only be told in brief – but it might do well to look now at the other two figures who figured in this epic event.

—————————————————————————————

Twenty-nine year-old city councilman Thomas Atkins was not a native New Englander; instead being born (appropriately enough for a musical story) in Elkhart, Indiana – the home of several musical instrument manufacturers. He overcame a bout of childhood polio to become the first African-American student president at both Elkhart High School and at Indiana University. Seven years before the US Supreme Court decided Loving vs. Virginia, he had to marry his college sweetheart in Michigan (as Indiana forbade interracial marriage). Atkins then pursued both a master’s (as well as his law degree) at Harvard, becoming the executive secretary of the NAACP as a law student.

Continuing his pioneering role, in 1967 he was the first black elected to Boston’s city council at-large – forthrightly campaigning in white neighborhood barrooms as well as in black districts. The busing crisis in the city saw threats against he and his family; his Roxbury home needed fortifications as a precaution. In 1971 he ran for the office of mayor (finishing in fourth place) and later that year was named to the cabinet of GOP governor Frank Sargent – the first African-American in a Massachusetts cabinet post (are you detecting a pattern here)?

During his time in public office, Atkins had risen to the rank of president of the Boston chapter of the NAACP and after leaving politics in 1975: eventually rose to be general council of the national NAACP. Following the suspension of executive director Benjamin Hooks, Thomas Atkins was named to replace him by NAACP chair Margaret Wilson. However, the organization’s board of directors voted to reinstate Hooks, so Atkins’ time in the top spot was limited. Atkins left the NAACP a year later, returning to private law practice.

Thomas Atkins died six years ago (June, 2008) of ALS – Lou Gehrig’s disease – at the age of sixty-nine. He once said that power was colorless. “It’s like water: you can drink it, or drown in it”. The Boston Globe concluded its editorial on his passing with, “Boston has seen more fiery civil rights leaders than Atkins – but none smarter or more strategic”.

While it was Thomas Atkins’ plan, and James Brown’s fulfillment that saved the night: someone still had to approve and help make the event happen.

And this was Boston’s mayor Kevin White – who had only been elected to office four months earlier (after a six-year stint as the Massachusetts secretary of state). Although coming in second to her in the city’s non-partisan primary, he was able to (narrowly) defeat desegregation opponent Louise Day Hicks in the runoff/general election, which enabled White to have some credibility with the city’s growing black population. In fact, one of White’s first-term aides – named Barney Frank – said he was dubbed ‘Mayor Black’ because he was the first mayor to acknowledge the city’s racial problems.

Kevin White went on to serve four terms as the city’s mayor, losing a campaign for governor in 1970 (to the aforementioned Frank Sargent) and was briefly the top choice of George McGovern to be his 1972 running mate: but was persuaded against by Ted Kennedy (as White had supported Edmund Muskie in the primaries). George McGovern said later he wished he had overruled Kennedy, after the Thomas Eagleton situation damaged his candidacy.

Although never charged with any crime, White did not seek a fifth term in 1983, as corruption charges involving municipal contracts swirled around his administration. He was credited with helping to revive the city’s waterfront, downtown and financial districts, and the Faneuil Hall/Quincy Market district that opened during his tenure (in 1976) has been widely copied by other cities. Interestingly, his appearance onstage with James Brown would not be his last with a major musical act at the Boston Garden.

Four years later in 1972: he persuaded the Rhode Island state police to release – into his own custody – a rock band (and members of their entourage) who had been involved in an altercation with a photographer and were subsequently arrested and put in jail. Mayor White realized the potential for violence to break out if the show did not go on and even helped arrange a police escort up Interstate 95.

The recently (and sadly) defunct Boston Phoenix cited as #3 of the 40 Greatest Concerts in the city’s history …. this show by the Rolling Stones – as the mayor boasted on-stage, “The Stones have been busted … but I have sprung them!”

Kevin White died in January, 2012 at the age of 82 – and there is a statue of the four-term mayor outside Faneuil Hall today.

One of the interesting aspects of that concert was that James Brown was not a natural ally of Dr. King. Cultural differences abounded, as Brown was not inclined to believe in a mass movement based upon shared beliefs. And as the Rev. Al Sharpton has noted, “He respected Dr. King, and knew that King had given his life. But he did not believe in nonviolence, he always told me. And he felt that Dr. King was not the grassroots guy he was”. This would not be the only time James Brown went against-the-grain: as he was later questioned about his entertaining the troops in Vietnam, making friends with VP Hubert Humphrey and eventually endorsing Richard Nixon’s re-election.

Ultimately, James Brown decided to put himself into honoring King, as he felt King was sincere, practiced what he preached and risked his life doing so. Still, he had some trepidation – would people criticize him for advocating non-violence now? And cast in the role of pacemaker, would he be blamed should violence break-out? Finally, would he and his band members risk being the victims of violence, as trombonist Fred Wesley later admitted? All of this lay beneath the surface as concert preparations were made.

Beforehand, he had given statements to black-owned radio stations, urging non-violence in the wake of the assassination. Then, due to a non-compete agreement (relating to a taped television show, not yet scheduled to air), Brown stood to lose $60,000 as a result of this last-minute decision. Finally, as word of the television show began to spread, ticket-holders began to appear at the Boston Garden box office, seeking refunds for a show they could watch at home for free (in the end, only 2,000 people attended the show, vs. a capacity of 14,000).

James Brown was hesitant – as he had dealt with unscrupulous promoters early in his career and was reluctant to forgo so much. “James, James,” pleaded Atkins. “We’ll work this out! But right now you have an opportunity to help save this city.” The mayor agreed, promising the city would make-him-whole (which seems a matter of dispute today, as to just how much actually was made-up) and the time came for the show itself.

Thomas Atkins first spoke, before Kevin White did. This had to be awkward for him: he had never heard of James Brown before (as was probably true for most white men older than age 35 in 1968) and backstage, he had addressed Brown as “Jim” (no doubt thinking of the famed NFL player). The mayor stumbled through words about honoring Dr. King, but beforehand James Brown had said it all:

“Just let me say, I had the pleasure of meeting him and I said, ‘Honorable Mayor,’ … and he said, ‘Look man, just call me Kevin.’

And look, this is a swingin’ cat. Okay, yeah, give him a big round of applause, ladies and gentlemen. The man is together!”

This helped set a tone of harmony for the show (and for the television audience).

One flashpoint that could have been a disruption was when several youths jumped on stage, grabbing the singer. And when the police forced them back, here was the worst possibility: white cops aggressively confronting (mostly) black youths on live TV. Here again, Brown stepped-in – asking the police to step-back, and then advising the audience of that request.

“I think I can get some respect from my own people”, and “Let’s respect ourselves. Are we together or are we ain’t?”

The response (and cooperation) he received set the tone for the rest of the show, which triumphantly achieved its objectives.

Film maker David Leaf (who already had The US vs. John Lennon to his credit) produced the aforementioned documentary entitled The Night James Brown Saved Boston – which was narrated by Dennis Haysbert, interspersing concert footage with commentary from Cornel West and Al Sharpton, recollections from journalists and band members who were present at the show.

Afterwards, praise began to drift in from different quarters after James Brown brought calm to a simmering city. “I remember going through the South End and every window seemed to be watching James Brown,” said Peter Wolf – the lead singer of the (Boston-based) J. Geils Band.

Barney Frank noted that “You never know what might have happened” otherwise, and the next month, James Brown was invited to a Washington state dinner for the prime minister of Thailand. When he took his seat, the singer found a note at the table saying, “Thanks much for what you are doing for your country, Lyndon Johnson.”

Despite the money dispute, the show became a major achievement of Brown’s illustrious career, right up to his death in 2006. And I gotta confess: when learning of the awful news that partly spoiled that Christmas Day – the thought crossed my mind that the Dutch techno band L.A. Style had their 1991 song’s famous chorus (in that nasally voice) finally come true, fifteen years later: “James Brown …….. is dead”.

In the aforementioned Boston Phoenix essay on the 40 Greatest Concerts in the city’s history: this show was voted #1 …. to no one’s surprise. Here is a partial set list from the show, and let’s close with the song that James Brown opened with … which was not one of his original compositions (although one he had recorded and often featured in his act).

That’s Life was written by Dean Kay and Kelly Gordon, and made famous two years earlier by Frank Sinatra. And below you can hear that night’s version.

That’s life, that’s what all the people say

You’re riding high in April

Then shot down in May

But I know I’m gonna change that tune

When I’m back on top in JuneI said that’s life and as funny as it may seem

Some people get their kicks

Stompin’ on a dream

But I don’t let it get me down

‘Cause this fine ol’ world keeps spinning aroundI’ve been a puppet, a pauper, a pirate,

A poet, a pawn and a king

I’ve been up and down and over and out

And I know one thing:

Each time I find myself, flat on my face

I pick myself up and get back in the race

1 comment