I woke up this morning thinking of my father, who was born on April 1, 1919. I’ve written about him here in the past. He was responsible for ensuring that though the schools I attended during my growing up period did not teach black history, culture, arts, literature and drama (most still don’t) that I would get a well-rounded education at home. So, I became just as familiar with African and Caribbean writers and thinkers, as I was with the work of Langston Hughes, and Richard Wright.

In my teenage and young adult years there were ideological schisms within the various black movements in the U.S.-cultural nationalism, revolutionary nationalism, pacifistic militancy and integrationism, separatism, black power, Pan-Africanism, the Black Arts movement…all of which would affect how I viewed the world and experienced myself as a black person. Later I realized that much of this theoretical and ideological push and pull and influences, which was so critical to my development is still virtually unknown and unacknowledged by the majority, who have neatly packaged black history into a nice tidy Martin Luther King package, rarely including Africa and the diaspora, except to tie it to slavery. Unless one is a student in black or african studies, the struggles against colonialism and neocolonialism in politics and culture are also absent from the curricula.

I remember talking to my dad about his interest in attending a cultural festival in Africa, and that the U.S. delegation was being headed by Langston Hughes, but I gave it little thought-I was away at school at the time, and my parents didn’t make the trip to Africa until several years later. I only recently realized that the festival he had spoken of was launched on his birthday.

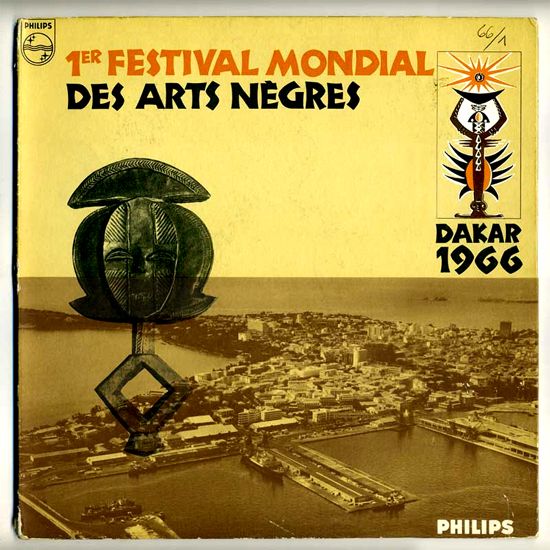

On April 1st, in 1969 the First World Festival of Black Arts (Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres) opened in Dakar, Senegal.

The World Festival of Black Arts was first held in 1966 in Dakar, Senegal. The festival was conceived by then president, Leopold Sédar Senghor. Senghor was a foundational member of the Negritude movement that sought to affirm and elevate the achievements of Black people and African culture throughout the world. A perfect expression of this mission, the first Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres was attended by people from 37 countries, and hosted many of the greatest Black cultural emissaries of the day including Duke Ellington, Aimé Césaire, and Josephine Baker.

The ideology behind the gathering was that of Négritude

Negritude was both a literary and ideological movement led by French-speaking black writers and intellectuals. The movement is marked by its rejection of European colonization and its role in the African diaspora, pride in “blackness” and traditional African values and culture, mixed with an undercurrent of Marxist ideals. Its founders (or les trois pères), Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and Léon-Gontran Damas, met while studying in Paris in 1931 and began to publish the first journal devoted to Negritude, L’Étudiant noir (The Black Student), in 1934.

The term “Negritude” was coined by Césaire in his Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (1939) and it means, in his words, “the simple recognition of the fact that one is black, the acceptance of this fact and of our destiny as blacks, of our history and culture.” Even in its beginnings Negritude was truly an international movement–drawing inspiration from the flowering of African-American culture brought about by the writers and thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance while asserting its place in the canon of French literature, glorifying the traditions of the African continent, and attracting participants in the colonized countries of the Caribbean, North Africa, and Latin America.

The movement’s sympathizers included French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and Jacques Roumain, founder of the Haitian Communist party. The movement would later find a major critic in Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian playwright and poet, who believed that a deliberate and outspoken pride in their color placed black people continually on the defensive, saying notably “Un tigre ne proclâme pas sa tigritude, il saute sur sa proie,” or “A tiger doesn’t proclaim its tigerness; it jumps on its prey.” Negritude has remained an influential movement throughout the rest of the twentieth century to the present day.

First World Festival of Negro Arts (full version), documentary by award winning black filmmaker William Greaves

(clip with Duke Ellington)

Later Black scholars would write harsh critiques of the event, and in 1969 Algeria would launch the “Festival panafricain d’Alger” in 1969, which was the subject of a full-length documentary by William Klein, with the same name.

The 1969 festival included not only artists like Miriam Makeba, Nina Simone, Archie Shepp, and Salif Keita, but also held political symposia.

A symposium was held to give a platform to speakers including Guinean revolutionary Amilcar Cabral, US Civil Rights activist Stokely Carmichael and Negritude theorist Leopold Senghor. “People came here specifically to check each other out,” says Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver in the film, “to see what was going on and to get some ideas as to which movement they could relate to.” An Afro-American Cultural Center was also opened and a Pan African Cultural Manifesto drawn up, calling for culture to form the basis of a new, empowered Africa.”I don’t think there will ever be any African festival like that,” says Niati.

Those gathered there, including many representatives of African Liberation Struggles, and the Algerian festival was an ideological counter-offensive against the first festival presenting a

Senghorian rather than Césairean vision of Negritude, targeting the conceptions and the attitude of the president-poet and not Senegal. In fact, many Senegalese intellectuals and artists were invited to Algiers and are visible and audible in the film. The policies of Senghor were judged to be overly dependent on Europe, his writings seen as conservative and too strongly influenced by colonial anthropology and a kind of consensual humanism.

The festivals in Africa continue, with many music festivals scheduled in 2014. The politics of the continent including many facts rarely discussed in US media, and few TM sources cover anything but chaos or tragedy. Sadly, for most Americans, Africa is still a “dark continent.”

But if African-American history is still ill taught, and Native Americans are still “invisible” I guess it is too much to expect that we would have a deeper knowledge of the diversity that is Africa.

Maybe one April in the future that will have changed.

For now, I’ll just sign off with a “Happy Birthday Dad”. Thanks for your teachings.

Cross-posted from Black Kos

5 comments