I am fascinated by the structures of the earth and how its most beautiful and intriguing features came about, and indeed are still forming. However, as a non-geologist, I am still boggled by the geologic time frame of millions of years. Millions of dollars seem to be tossed around a lot and are of little significance anymore in some circles. But millions of years to a non-geologist remains difficult to conceptualize.

Geologic feature in Chuckanut Bay

During the Eocene Epoch (56 to 33.9 ma), say a mere 50 million years ago (Ma), my part of the world in the northwest corner of Washington State was a subtropical swamp. My backyard was essentially flat with large river drainages that meandered maybe 150 miles to the Pacific Ocean from what is now Central Washington.

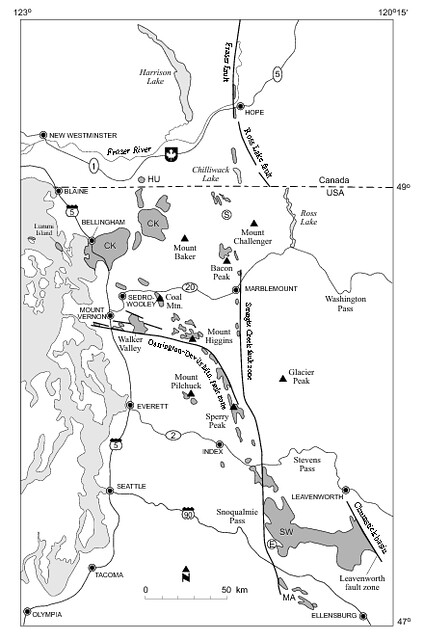

Our area was a fluvial plain of deposited sediment much like the Mississippi River delta today drops silt as it slows and emptys into the Gulf of Mexico. For over 22 million years, silt, sand, and gravel were washed along and deposited on their way to the Pacific. Over time these deposits hardened into layers of sandstone, shale, and siltstone, along with some conglomerate that run as deep as 6,000 meters. Our local sedimentary formation, called the Chuckanut Formation was named for the Chuckanut Mountains just south of Bellingham WA. Remnants of this sedimentary sandstone formation extend north, south, and eastward, up into what is now the Cascade Mountains. The original formation has been disrupted by erosion, volcanic activity, by faults, and thrusting tectonic forces that eventually formed the Cascade Mountain range.

The areas in the upper left hand corner of this map marked CK, are the remnants that compose the major portion of the Chuckanut Formation. They are on the bay, west of Mt. Baker and south of the Canadian Border.

The various pieces of the original terrane are scattered as shown in the map, (CK) but they can be identified by their composition materials as being from the same source. The source was what is now Mt. Stuart in the central Washington in the eastern part of the North Cascades Mountains.

Mt. Stuart, central Cascades

Mount Stuart is the second highest non-volcanic peak in the cascades and is the largest chunk of exposed granite in the contiguous forty-eight states.

Related deposits were laid down in this part of the world throughout the Eocene epoch but I will focus here on the Chuckanut Sandstone Formation.

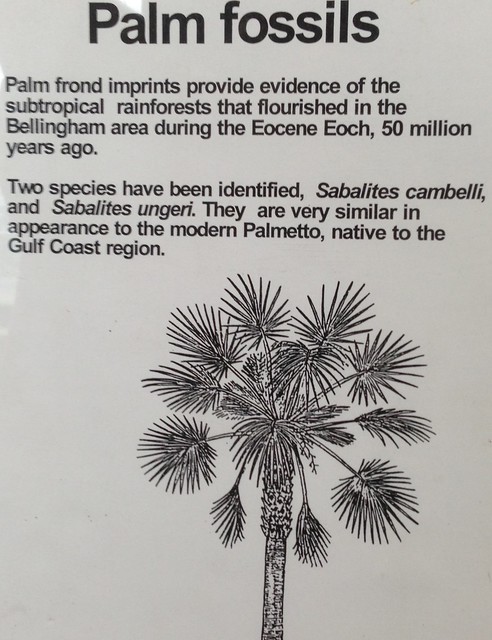

As a subtropical climate would imply, there was an abundance of plant and animal life with non-freezing temperatures thought to be about like current day San Diego and subtropical Mexico. The abundant vegetable matter laid down also formed coal deposits found throughout the area. And as expected, there would also be an abundance of fossil remains to inform us of the flora and fauna that grew here while giving us clues to the climate.

To give you some feel for what this formation looks like, here is a view of some soft sandstone cliffs at the water’s edge in Chuckanut Bay. You can see how the wind and water have eroded and sculpted the relatively soft sandstone into some artistic looking shapes.

Sandstone cliff at Clark’s Point, Chuckanut Bay

The structures protruding from these cliffs have a long history and much lore, as well geological analysis. This is a well known site on Clark’s Point in Chuckanut Bay at the foot of Chuckanut Mountain. The initial photo in this diary comes from this sandstone cliff. For years I and many others assumed these were giant palm tree trunks. This being a subtropical forest, the area was covered in palms from which both fossilized fronds and trunks are readily available for easy identification.

This remnant encased in sandstone of the Eocene would seem to the untrained eye, including my own until I learned otherwise, to be a giant fossilized palm tree. It is not. The geologists who have studied this area intensely have concluded that it is a Pseudofossil, and an example of a concretion.

Pseudofosssil

As is the structure in the initial photo, this too is a pseudofossil, found just a few meters apart.

A concretion is a bit of a geologic oddity.

A concretion is a hard, compact mass of sedimentary rock formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between the sediment grains. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular shapes also occur. The word ‘concretion’ is derived from the Latin con meaning ‘together’ and crescere meaning ‘to grow’. Concretions form within layers of sedimentary strata that have already been deposited…This concretionary cement often makes the concretion harder and more resistant to weathering than the host stratum.

Here are some more examples of concretions. Note their ovoid shape. One looks like a giant egg, once postulated to be a dinosaur egg. But it is nothing so interesting, just another concretion.

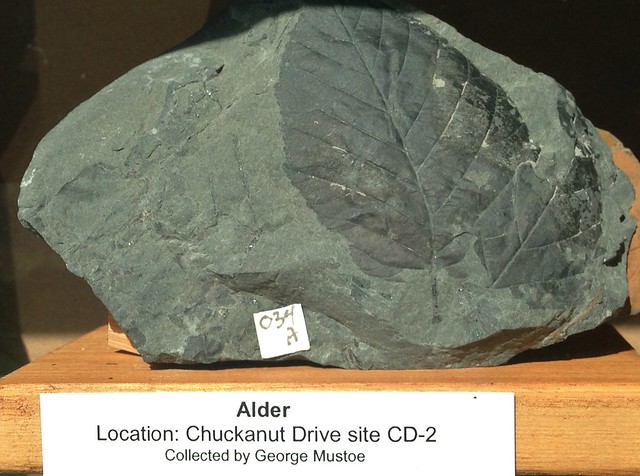

However, there are plenty of real plant fossils from this same formation to satisfy anyone and they do not look at all like the pseudofossil. Below are a few such fossils that are on display in the Geology Department at Western Washington University.

The Chuckanut flora is made up predominantly of plants whose modern relatives live in more tropical areas such as Mexico and Central America. However, a number of plants have survived or have come back and are found here today.

Three of the most common fossils are Sabalites palm

fronds, fronds of a tree fern, Cyathea pinnata, and

foliage of Glyptstrobus, a conifer. More than 30 species of

angiosperms are represented by leaf and seed fossils.

Palms:

Below are some palm tree trunks that look very little like the pseudofossils above.

And some palm fronds, similar to those seen in the Southeast US and further south.

Horsetails: relatives of the indestructible scourge of many a garden. Its tree sized ancestors flourished here as forests.

Ferns were plentiful here during the Eocene and continue to thrive in our moist climate today.

Fern frond (Cycad, dioon)

Tree fern, (Cyathea pinnata) found today in warmer climes.

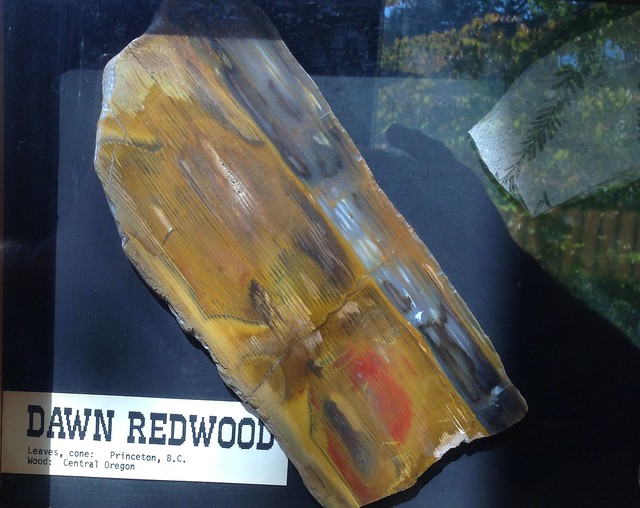

A few other recognizable trees:

Sycamore (platanus)

Sassafras Leaves

Dawn Redwood (Meta sequoa Occidentalis)

Alder (Alnus)

Also found in this formation are fossils of a variety of conifers, as well as a relative of the flowering bush, Hydrangea. It seems that much would be familiar to us if we were to travel back a few million years. However, the time frame still boggles me.

In the 2nd part I will examine some of the fauna that inhabited this swampland during the Eocene Epoch.

7 comments