I spent yesterday, Labor Day, thinking about the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and my family ties to that union who played such an important role in black history.

One of the books I suggest you read if you are interested in both black history and sociology and the development of the labor movement is Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class, by Larry Tye

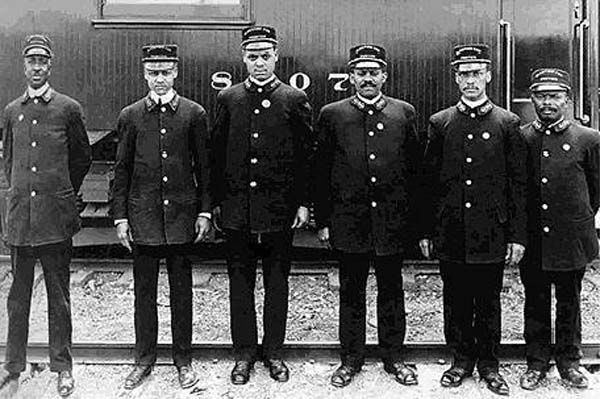

Although Tye focuses on Pullman porters and the formation of the black middle class, his analysis of class perceptions and race relations reverberates to the current day. Following Reconstruction, industrialist George Pullman took advantage of the limited opportunities available for freedmen, hiring and exploiting blacks–the darker the better–to serve as porters on his railroad. The porters suffered low wages, long hours, and weeks if not months away from home. In addition, they were expected to adopt a servile demeanor to provide comfort to the mostly white patrons of the Pullman sleeping cars. But the upside was employment, travel, and middle-class values and opportunities. Moreover, the fight for union recognition through A. Phillip Randolph’s leadership was the basis for progress for blacks during the pre-civil rights era. The porters’ labor dispute and efforts to include blacks in more favorable positions in the war industry led to the first march on Washington. Tye also explores the tension between the perception of Pullman porters as docile servants and their challenge to the status quo. Vernon Ford

James A. Miller, professor of English and American Studies and director of Africana Studies at George Washington University, reviews Tye’s book in A quiet route to revolution:Pullman porters played role as ‘agents of change’

Tye depicts the struggle of the porters in heroic terms, casting them as the vanguard of a black community seeking to negotiate its relationship to an American society whose terms, rituals, and etiquette — at least in the decades following the Civil War — remained remote and unfamiliar: “Porters were agents of change. . . . They carried radical music like jazz and blues from big cities to outlying burgs. They brought seditious ideas about freedom and tolerance from the urban North to the segregated South. And when white riders left behind newspapers and magazines, porters picked up bits of news and new ways of doing things, refining them in each place they visited, and leaving behind a town or village that was a bit less insular and parochial.”What they saw and read changed them, too. It made porters determined that their children would get the formal learning they had been denied. . . . Through their time on the train these black porters learned the ways of a white world most had only vague exposure to before, coming to know how it worked and how to work with it.”

Tye’s desire to place a human face on these workers is very much at the heart of “Rising From the Rails.” Drawing upon extensive and meticulous research — as well as in-depth interviews with 40 or so former porters and their families — he depicts the absorbing saga of the Pullman porter, a story firmly rooted in the dynamic growth of the American railroad in the years following the Civil War. It is a tale populated by larger-than-life figures like Pullman, the visionary and ruthless capitalist whose unconventional tactics and attitudes qualified him, in Tye’s view, as a racial “moderate if not a reformer”; Robert Todd Lincoln, the son of the Great Emancipator, who presided over an era marked by both unprecedented growth and labor repression at the Pullman Co.; and A. Philip Randolph, “Saint Philip,” the eminent and outspoken Socialist and labor leader who — along with Milton P. Webster, Ashley L. Totten, and C. L. Dellums — spearheaded the effort that led to the triumphant emergence of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1937.

The story does not end there, for Tye makes a compelling case for the intricate connections between the porters’ struggles for economic justice and the quickening pace of the civil rights movement in the 20th century — from the formation of the National Negro Congress in the mid-1930s to Randolph’s threatened 1941 march on Washington to the 1963 march on Washington, and beyond. Throughout, Tye sustains our interest, weaving together several levels of narrative while keeping the stories of ordinary porters squarely at the center. The result is a lively and engaging chronicle that adds yet another dimension to the historical record.

Tye’s book later became the basis for a documentary film with the same name.

Too often when we discuss the civil rights movement we don’t tie it in with the labor movement and the first powerful black union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

You won’t have to go very far, or dig very deep to find black Americans who can tell you stories about fathers, or grandfathers or uncles who worked as Pullman porters and waiters.

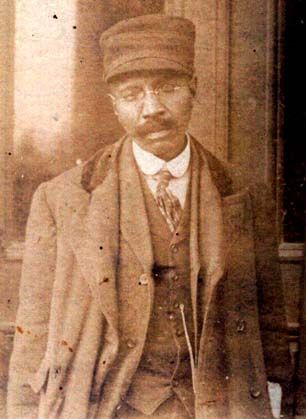

My grandfather, my mom’s dad, Dennis Presley Roberts, is one of those stories.

Born on Jun 24 1874, in Loudoun County Virginia, he was the son of two former slaves. His mother swore that all of her children would become educated, and Dennis took on that task, not only for himself, but for all his brothers and sisters. He learned to read and write in a one room schoolhouse, and migrated to nearby Washington DC, to work as a waiter, and attend Wayland Seminary (which merged with Virginia Union) which he graduated from in 1897. Not content to become (as he put it) a “jack-leg preacher”, he decided not to further his education, and the economic pressures to assist his younger brothers and sisters pushed him to taking a job on the railroad.

Dennis was canny about finance, and saved his salary and every tip from the elite whites he waited on daily, to buy houses. Recognizing the need for black apartments in the growing black metropolis of DC, Dennis bought first one building, and then another. One of the buildings he owned was at 1523 T Street NW. (I had to laugh when I looked up what that building is worth now – $1,132,020). As the self-appointed patriarch of the family he was a bit of a martinet. Just like the trains ran on time granddaddy Dennis did everything on a schedule. He wore a watch on a chain which he constantly referred to. He also brooked no talk back. He ordered the lives of his siblings, telling John to teach, Joseph to go to medical school, James was to become a dentist, and that the girls, Hannah and Martha would go to teachers college. He helped them all pay their school fees.

He was soft-spoken, and always impeccably dressed. My mom says she never saw him in his shirtsleeves, though he did have a smoking jacket he wore when he was “relaxed”. In 1907 he married a beautiful young woman, also from Loudoun County who was working as a domestic in New Jersey, and soon moved his young family to New London Connecticut, since by that time he was working on the New York to New Haven line. After the birth of his first four children, he relocated the family to the Bronx, where his wife died after giving birth to my mom. Undaunted, he refused to split up his children and parcel them out to different relatives. Instead, he ordered his widowed sister Martha to leave DC, used his funds to help establish his younger brother the doctor in Philadelphia, helping him buy a large home, and moved Martha and the children in with Dr. Joe. Joe’s practice flourished, and as a consequence my mom was raised in a home with a cook, a laundress and two maids. Granddaddy Dennis bought another building in Philly with an ice cream parlor on the ground floor for Martha to run.

He never stopped working the trains. Once a month he would arrive in Philadelphia to “inspect” his children and monitor their schooling and manners. My mother remembers him ruefully stating that he would earn more money in tips if he adopted an uneducated speech pattern and obsequious attitude, but there was no way he was going to bend. He raised his children to be Negro and proud and to never cross a picket line. Family members of the porters got to travel the railroad free, and my mom used to go each summer down to DC from Philly, traveling under the watchful eye of his “brother” waiters and porters. It was like having a family that extended across the U.S.

His story is really no different than that of his brother porters. White passengers saw only black servants, never imagining that these men were buying property, sending their progeny to colleges and universities, and funding the growing civil rights movement. Their union, led by socialist A.Philip Randolph, would become a powerful voice for change, affecting not only the segregated labor movement, but the course of the nation.

There are many other books and films exploring the Pullman porter’s lives and union movement. California Newsreel distributes Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle, winner of four regional Emmy Awards, produced by Jack Santino and Paul Wagner. Jack Santino is the author of the book, Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle – Stories of Black Pullman Porters.

Miles of Smiles chronicles the organizing of the first black trade union – the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This inspiring story of the Pullman porters provides one of the few accounts of African American working life between the Civil War and World War II.

Miles of Smiles describes the harsh discrimination which lay behind the porters’ smiling service. Narrator Rosina Tucker, a 100 year old union organizer and porter’s widow, describes how after a 12 year struggle led by A. Philip Randolph, the porters won the first contract ever negotiated with black workers. Miles of Smiles both recovers an important chapter in the emergence of black America and reveals a key source of the Civil Rights movement.

Labor Day may have passed, but our labor to build a movement that will change this nation is no where near over. Black union members are still playing a key role in the struggle. They stand on the shoulders of the Brotherhood.

Crossposted from Black Kos

6 comments