With the 2013 Newport Jazz Festival coming this weekend: perhaps its most magic moment took place fifty-seven years ago, after the jump ….

On the 7th of July, 1956: the world was still in a transitional period following World War II (and yours truly was two months away from birth). The jazz world was gathering in Rhode Island to perform at only the third edition of the Newport Jazz Festival and one of the performers saw it as a make-or-break time for he and his band. A newcomer? Someone returning to the stage from a stint in prison? A musician for the first time leading his own band? Hardly.

While there will never be consensus on this: along with Leonard Bernstein, I would list Duke Ellington as the Total Musician of the 20th Century – in terms of individual performance, composing, bandleading, music education and being a musical ambassador for his country. He had an orchestra that – even in the Big Band era – was known for having musicians who stayed with him for many years (when other Big Band era musicians were eager to leave as soon as they were able to) and when asked what was his secret was replied, “I pay them”. The list of honors and awards he received include 12 Grammy Awards, a Pulitzer Prize, Presidential Medal of Freedom, induction into both the Jazz and Songwriter’s Halls of Fame, and even his own US postage stamp – just for starters.

Yet much of these awards could have been bestowed simply based upon the work he did in the 1920’s, 1930’s and 1940’s.

For, come the mid-1950’s …. Duke Ellington (at age 57) and his Orchestra were increasingly looked at as an anachronism. The advent of TV enabled people to entertain at home like never before, the early days of R&B and rock music – though still unsteady at this time – were starting to affect the music landscape, and the economics of post-war America had made large bands very expensive to bring on the road. This led to the rise of hip small ensembles: and Miles Davis, Chet Baker/Gerry Mulligan, Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus and others in the bebop movement were beginning to change the modern jazz landscape. In fact, at that time the Ellington Orchestra did not even have a recording contract, and were occasionally doing shows in skating rinks just to stay busy.

But fortunately, record producer (and A&R man) George Avakian – who is still alive today, at age 94 – had convinced Columbia Records to allow him to record the entire festival for what would prove to be the first live recordings on the relatively new Long Playing Records (or LPs) – and the jazz festival was a relatively new phenomenon they wanted to showcase. Columbia wound up subsidizing the festival – agreeing to pay all of the artist fees in return for the recording rights. This convinced Ellington that he had a unique opportunity for a change-of-fortune.

They played their first set at 8:30 PM and things did not begin well: as four of his musicians were not to be found by showtime, and the set was cut short. Due in part to thunderstorms, they began their second set after 11:30 PM, when Duke feared many spectators would be leaving for home – and not without reason, as this was an upper-class audience that was fairly sedate, so there was no telling how they’d respond. But with a full lineup, the band did now start to settle in, with solid renditions of “Take the A Train”, “Sophisticated Lady”, a new Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn composition “Newport Jazz Festival Suite”, and “Day In, Day Out”. The audience was enjoying itself, albeit quietly.

Duke next decided to dust off a pair of 1937 blues tunes that appeared on both sides of a 78-rpm record: “Diminuendo in Blue” and “Crescendo in Blue” (almost antonyms) and told the audience they were now being linked together with an improvisation by one of his sidemen to form Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue – a performance that changed the jazz world … and the fortunes of Duke Ellington and his Orchestra for the rest of his life.

Interestingly, the choice of tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves (photo right, below) was not one of Ellington’s featured sidemen; the announcement of his name did not bring forth a loud response. But there was some response, and for a very appropriate reason.

Paul Gonsalves was a native New Englander (born in Brockton, Massachusetts) and, like the pianist Horace Silver: was the son of immigrants from Cape Verde – an African island nation colonized for centuries by Portugal – so he often performed at clubs in Rhode Island, New Bedford and Fall River, which had a notable ethnic Portuguese and Cape Verdean population. Thus, Gonsalves had family and friends in attendance; seated in rows just behind the box seats of Newport socialites.

But in a sign reminiscent of the first-set troubles: when it came time for Gonsalves’ tenor solo, he actually blew not into the Columbia microphone, but into the alternate Voice of America microphone – which had only recently begun to feature a nightly “Jazz Hour” for broadcast outside the United States (which I profiled in a previous Top Comments diary) – which would affect the recording of the show for the subsequent Columbia release.

But not for the show itself: because Gonsalves delivered a tour-de-force blues in-the-key-of-D that stood out for three major reasons:

One was that – instead of playing a smooth, big-band style of playing – he played in a deep Gospel, R&B honking style that was more suited for juke joints and church revival meetings … not what sedate, wealthy audiences were expecting.

The second was that the rest of the horn/reed players (on cue) “laid-out” (stopped playing) so that all Gonsalves had as back-up was bassist Jimmy Woode, drummer Sam Woodward and Duke himself on piano – lending the sound more toward a rocking small quartet. Actually, there was a fifth performer: at the foot of the stage was Jo Jones – the former drummer for Count Basie, now appearing with pianist Teddy Wilson – who was serving as another percussionist by banging a rolled-up copy of the Christian Science Monitor – whose offices are in Boston – on the stage, and shouting more encouragement.

The last reason was that – in normal big bands – a soloist on a blues tune might expect to play two, perhaps three choruses. Later musicians (such as John Coltrane) were used to playing extended solos in small groups – just not in big bands. Gonsalves, though – egged-on by Duke Ellington, urging him to “wail” – played for twenty-seven choruses – over six minutes – until he could no longer blow. And by the sixth-or-seventh chorus, his wailing had led a 32 year-old socialite (the wife of a clothing manufacturer) in a black dress who was so moved by the music that she got up and …. started dancing. And a (partially obscured) photo of her appeared on the album cover months later.

That opened the floodgates: a couple started jitterbugging and others stood on their chairs, roaring their approval. When the rest of the band came back to finish with the “Crescendo in Blue” portion, the ovation the band received at song’s end was described as one of the loudest in jazz history and the post-midnight commotion had the Newport security police on alert. On the audio recording embedded below, you hear Duke saluting his band and calling out “Paul Gonsalves ….. PAUL GONSALVES!” to a delirious audience.

The band completed its set – including the triumphant return of alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges after a five-year hiatus – to play a spirited version of “Jeep’s Blues” to a still-animated audience. In fact, Duke needed to play a subdued version of “Mood Indigo” to bring the audience down at the set’s conclusion.

Two results from the festival were: (1) Duke making the cover of TIME Magazine – at the time, only the third jazz musician to be so honored (with Louis Armstrong and Dave Brubeck preceding him and, years later, Thelonius Monk as well as Wynton Marsalis following him).

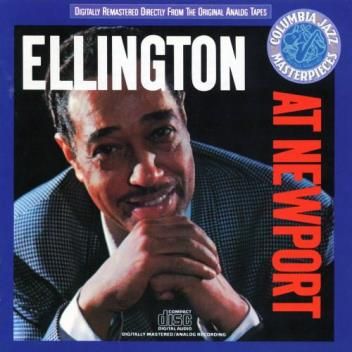

And (2) was the release of this album – yet which has an interesting provenance, based in part on Gonsalves blowing into the wrong microphone. In fact, after the festival, the band went into the studio to re-record several passages that were sub-par. Not because Columbia Records (in general) or producer George Avakian (in particular) asked them to do so … but because Duke wanted this release to be first-rate so badly, this 1956 release had overdubbed parts. Notable was Johnny Hodges’ playing on “I Got it Bad” and Paul Gonsalves’ entire solo re-done – in all, more than 50% of the album was overdubbed.

Duke apparently knew what he was doing: with the album becoming a Columbia masterpiece, earning five star reviews. Indeed, when asked for his date of birth he often replied, “I was born at Newport in 1956.”

Before we hear the song, some codas to the key participants.

(a) Duke Ellington endured, responding to inquiries about when he might retire with, “Retire to what?” with successful tours and albums. He died in May, 1974 at the age of 75.

(b) Paul Gonsalves died in London just ten days before Duke Ellington’s death (after a lifetime of addiction to alcohol and narcotics) in 1974 at the age of 53. In fact, Duke’s son Mercer Ellington refused to tell Duke of Paul’s death, fearing the shock might have further accelerated his father’s decline.

(c) In 1996, the second tape of the Newport performance – the Voice of America recording – was located. And due to its superior quality (and the far, far better technological fixes now available) in 1999 the album was re-released – in a superior version. It was only then (more than twenty years after the death of Duke Ellington) that the general public was made aware of the earlier “hybrid” recording … which was now supplanted by a recording much closer to the original performance.

(d) Finally, the identity of the woman in the black dress was also revealed: Elaine Zeitz Anderson – who had been a dancer in her youth, and confessed she had “one martini too many” that evening – met George Avakian the following year. ”She came up and said why didn’t I use a better picture of her, and I said, because my attorneys had said she might sue,” Avakian recalled. ”She said, ‘Sue? I’d have been thrilled to death.’ ”

Elaine Anderson’s husband was mortified by her dancing that night(!), just one of several reasons that led to their eventual divorce. She eventually became head of a Boston nonprofit group Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay, which aims to preserve the architecture and community. Elaine Zeitz Anderson died in April, 2004 at the age of 80.

——————————————————————————————

I believe this is the re-mixed/remastered 1999 version of Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue – with the original solo by Gonsalves lasting over six minutes (from the 4:05 to the 10:20 minute-mark of the song. And below you can listen to it.

3 comments