As August 1st approaches, the day the British passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, which would be put in effect, August 1, 1834, freeing over 700,000 people held in bondage, which is celebrated in parts of the English speaking Caribbean as “Emancipation Day”, this last month has seen debate and discussion throughout the Caribbean, and in Great Britain, France and the Netherlands about a somewhat surprising unanimous statement issued by CARICOM in July on their final meeting day.

Caribbean nations launch joint effort for slavery compensation former colonial powers

Leaders of more than a dozen Caribbean countries are launching a united effort to seek compensation from three European nations for what they say is the lingering legacy of the Atlantic slave trade.

The Caribbean Community, a regional organization that typically focuses on rather dry issues such as economic integration, has taken up the cause of compensation for slavery and the genocide of native peoples and is preparing for what would likely be a drawn-out battle with the governments of Britain, France and the Netherlands.

Caricom, as the organization is known, has enlisted the help of a prominent British human rights law firm and is creating a Reparations Commission to press the issue, said Ralph Gonsalves, the prime minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, who has been leading the effort.

The Meeting agreed to the establishment of a National Reparations Committee in each Member State with the Chair of each Committee sitting on a CARICOM Reparations Commission. The Heads of Government of Barbados (Chair), St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Haiti, Guyana, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago will provide political oversight.

The decisions were taken followed presentations by Member States, led by St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and their unanimous support of the road map.

Chair of the Community, the Hon. Kamla Persad-Bissessar, Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, at an end-of-Meeting Press Conference at the Hilton Hotel, described progress on the subject as a very positive outcome.

Earlier in the day, during his contribution to the discussions, Prime Minister Baldwin Spencer said he conceptualized the call for reparations as an integral element of the Community’s development strategy. The legacy of slavery and colonialism in the Caribbean severely impaired the Region’s development options.

“We know that our constant search and struggle for development resources is linked directly to the historical inability of our nations to accumulate wealth from the efforts of our peoples during slavery and colonialism. These nations that have been the major producers of wealth for the European slave-owning economies during the enslavement and colonial periods entered Independence with dependency straddling their economic, cultural, social and even political lives”, Prime Minister Spencer said.

Reparations, he added, had to be directed toward repairing the damage inflicted by slavery and racism.

“We, as political leaders, must encourage our various reparation agencies to continue the education of our Caribbean people and our Diaspora, and enhance their awareness of the reparations issue. It is important that there is solid people and multi-party support for our efforts and we must impress on our colleagues in both Government and Opposition that this is not an issue we should use as party-politics fodder. Our various reparation organizations must see the forging of bi-partisan political support and civil society consensus for reparations as one of their main objectives,” the Antigua and Barbuda Prime Minister added.

CARICOM, the Caribbean Community (formerly the Caribbean Free Trade Association- CARIFTA) members are: Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname,Trinidad and Tobago.

CARICOM Associate members are: Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, and CARICOM Observers are Aruba, Colombia, Curaçao, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Sint Maarten and Venezuela.

News of the declaration has been covered widely in Caribbean media outlets.

Calls for reparations are not new. Before he was removed from office in 2003, Aristide raised a hue and cry about the fact that Haiti actually had to pay France for winning its revolution.

In 2003, then-President of Haiti Jean-Bertrand Aristide demanded that France pay Haiti over 21 billion U.S. dollars, what he said was the equivalent in today’s money of the 90 million gold francs Haiti was forced to pay Paris after winning its freedom from France as the hemisphere’s first independent black nation 200 years ago. “Some analysts believe that France’s refusal to support the deployment of an international peacekeeping force to Haiti until after the president’s departure was linked to Aristide’s demand for reparations, which were unpopular in Paris.

The British press has also dealt with the irony of slave profiteers being compensated.

Britain’s colonial shame: Slave-owners given huge payouts after abolition

The British government paid out £20m to compensate some 3,000 families that owned slaves for the loss of their “property” when slave-ownership was abolished in Britain’s colonies in 1833. This figure represented a staggering 40 per cent of the Treasury’s annual spending budget and, in today’s terms, calculated as wage values, equates to around £16.5bn.

A total of £10m went to slave-owning families in the Caribbean and Africa, while the other half went to absentee owners living in Britain. The biggest single payout went to James Blair (no relation to Orwell), an MP who had homes in Marylebone, central London, and Scotland. He was awarded £83,530, the equivalent of £65m today, for 1,598 slaves he owned on the plantation he had inherited in British Guyana.

But this amount was dwarfed by the amount paid to John Gladstone, the father of 19th-century prime minister William Gladstone. He received £106,769 (modern equivalent £83m) for the 2,508 slaves he owned across nine plantations. His son, who served as prime minister four times during his 60-year career, was heavily involved in his father’s claim.

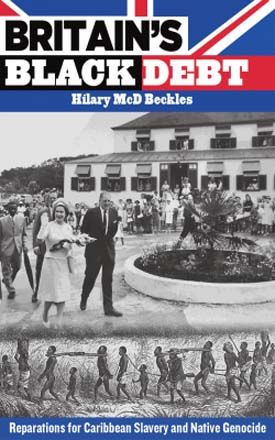

One of the foremost scholars from the Caribbean, Sir Hilary McD. Beckles, who “holds a Chair in Social and Economic History, University of The West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados, where he is also Principal and Pro-Vice Chancellor” has recently published “Britain’s Black Debt: Reparations for Caribbean Slavery and Native Genocide

Since the mid-nineteenth-century abolition of slavery, the call for reparations for the crime of African enslavement and native genocide has been growing. In the Caribbean, grassroots and official voices now constitute a regional reparations movement. While it remains a fractured, contentious and divisive call, it generates considerable public interest, especially within sections of the community that are concerned with issues of social justice, equity, civil and human rights, education, and cultural identity. The reparations discourse has been shaped by the voices from these fields as they seek to build a future upon the settlement of historical crimes.

This is the first scholarly work that looks comprehensively at the reparations discussion in the Caribbean. Written by a leading economic historian of the region, a seasoned activist in the wider movement for social justice and advocacy of historical truth, Britain’s Black Debt looks at the origins and development of reparations as a regional and international process. Weaving detailed historical data on Caribbean slavery and the transatlantic slave trade together with legal principles and the politics of postcolonialism, Beckles sets out a solid academic analysis of the evidence. He concludes that Britain has a case of reparations to answer which the Caribbean should litigate.

International law provides that chattel slavery as practiced by Britain was a crime against humanity. Slavery was invested in by the royal family, the government, the established church, most elite families, and large public institutions in the private and public sector. Citing the legal principles of unjust and criminal enrichment, the author presents a compelling argument for Britain’s payment of its black debt, a debt that it continues to deny in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

It is at once an exciting narration of Britain’s dominance of the slave markets that enriched the economy and a seminal conceptual journey into the hidden politics and public posturing of leaders on both sides of the Atlantic. No work of this kind has ever been attempted. No author has had the diversity of historical research skills, national and international political involvement, and personal engagement as an activist to present such a complex yet accessible work of scholarship.

Here is news coverage of Beckles calling on CARICOM to take action.

Activists in the U.S have raised similar cries here, from the “40 acres and a mule” question, which was not about broad reparations, but about land redistribution, though the term has come to symbolically represent reparations in general, which is why Congressman Conyers’ reparations bill is named “HR 40“, to words alluding to a debt owed in the Rev Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s “I have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” in which he stated:

So we have come here today to dramatize an appalling condition. In a sense we have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.

This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.

Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation.

Too often, when discussing the affect today of genocide and slavery, responses range from “get over it” to “but that was history”.

Can we honestly look at the conditions of the indigenous and black populations here in what became “the New World” and avoid admitting that the current economic and social conditions we face in our communities, including the legacy of racism, which is alive and well, are not attributable to the past, which for many of us is not shrouded by time.

What to do about it is an ongoing debate. One that may take many more decades to resolve. In the U.S. apology for slavery which passed the Senate June 18, 2009, a clear disclaimer was tacked on, which troubled some legislators:

DISCLAIMER- Nothing in this resolution–(A) authorizes or supports any claim against the United States; or

(B) serves as a settlement of any claim against the United States

My own position on reparations is that what is needed is a massive domestic Marshall plan, coupled with sweeping changes made in the drug laws and criminal justice system.

What are your thoughts on this issue?

Cross-posted from Black Kos

9 comments