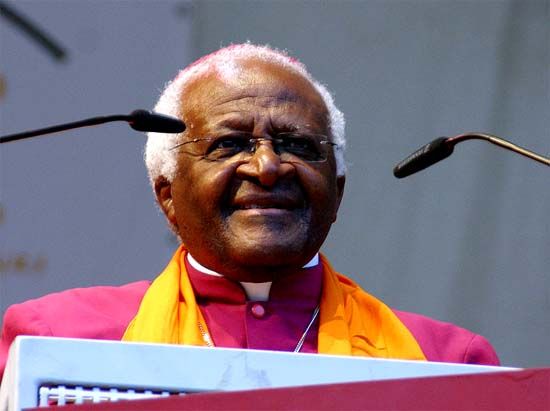

There are few people in the world who do not know the face of Desmond Tutu. When Nelson Mandela appointed him to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, he became the public face of an extraordinary process that few people could have even dreamed of or imagined during the long hard years of battling the brutal Apartheid regime.

The road to reconciliation was not easy.

The lack of racial harmony in the country between 1960 and 1994 prompted the first democratically elected government of Nelson Mandela to institute, in 1995, a commission of inquiry based in Cape Town (known as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission or TRC) into all apartheid-related crimes with the objective of mending hitherto unbridgeable racial disparities. Thus, when South Africa emerged from the nightmare of apartheid, the country launched a new struggle to deal with a history of pervasive human rights violations while at the same time working to unite and rebuild the nation.

Some Black people wanted harsh penalties for the perpetrators of apartheid crimes. Others thought that investigation of past wrongs would jeopardise the fragile new democracy, while others simply wanted to forget the past. In the end, the new government opted to establish a commission to document what happened during South Africa’s most troubled times, and offer limited amnesty to those who confessed their complicity. The TRC was based on the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, No 34 of 1995. It resembled a legal body that was bestowed with the authority to hear and try cases, resolve disputes, or make certain legal decisions. The policy of reconciliation embodied in the inquiry was predicated on the fundamental principle that “To forgive is not just to be altruistic, [but] it is the best form of self-interest.”

Desmond Tutu and the TRC

A year after the attainment of majority rule, Archbishop Desmond Tutu was appointed chairman of the TRC. Its jurisdiction included providing support and reparation to victims and their families, and compiling a full and objective record of the effects of apartheid on South African society. Anybody who was a victim of violence was welcome to give his or her testimony before this newly constituted body. Perpetrators of violence could also give evidence and request amnesty from prosecution.

The Government envisioned the TRC as a mechanism that would help deal with the evils of apartheid. In the words of the former Minister of Justice, Dullah Omar, the commission was “… a necessary exercise to enable South Africans to come to terms with their past on a morally accepted basis and to advance the cause of reconciliation.” The application of the system of apartheid had led to the escalation of conflict in the country which resulted in violence and human rights abuses. No section of society escaped these abuses, but, to the South African government’s credit, it was recognised that “to err is human but to forgive is divine.”

For the past three weeks, I have been writing about national apologies, and attempts at reconciliation in countries where a minority has been harmed, historically, and where they are still suffering the depredations of systemic inequities and racism.

We stand at a cross-roads here in the United States. We are moving into a future, where one day very soon, those people we now classify as “minorities” (a word I don’t like) will become the majority population. South Africa is an example of the majority working on healing its grief, pain and suffering and learning to co-exist with those who had been the ruling minority. No process is perfect, and South Africa still has its problems, but for me, South Africa has been a powerful example of human potential for good, even in the midst of so much ugliness that we see around us.

I would like to think that my brothers and sisters of color here in the U.S.-black, brown, red or yellow-will one day show the same spirit of forgiveness and redemption.

I hold out hope that we will not have to wait till then, and that the process could begin sooner. That, frankly, will be the decision of what is still a white majority here. A white majority that is deeply divided-between those who look towards the future, and those who want to cling to the racial divides and privileges of the past.

Collective Responsibility, “Sorry is not just a word, it’s a deed, an act.”

In this video clip from Facing the Truth, with Bill Moyers, South African poet, journalist and peace activist Don Mattera discusses the collective attitude of avoiding responsibility he sees in white South Africans.

“Confronting the Truth”shows how countries, which have experienced massive human rights violations, have created official, independent bodies known as truth commissions

Another highly recommend film on the South African process is Long Night’s Journey Into Day.

Truth and Reconciliation commissions are being used a tool worldwide. This is documented in the film Confronting the Truth.

Since 1983, truth commissions have been established in over 20 countries, in all parts of the world. Confronting the Truth documents the work of truth commissions in South Africa, Peru, East Timor, and Morocco. Taking testimony from victims and perpetrators, and conducting detailed investigations, truth commissions create a historical record of abuses that have often remained secret. They identify patterns of abuse, and the structural and institutional weaknesses, and societal and cultural problems, and weak legal systems that made the violation possible. To remedy these faults, they recommend governmental, societal and legal reforms to address the pain of the past, to safeguard human rights and due process, and to ensure that the horror will not be repeated.

Truth and reconciliation is deeply rooted in the concept of restorative justice.

Restorative justice (also sometimes called reparative justice) is an approach to justice that focuses on the needs of the victims and the offenders, as well as the involved community, instead of satisfying abstract legal principles or punishing the offender. Victims take an active role in the process, while offenders are encouraged to take responsibility for their actions, “to repair the harm they’ve done-by apologizing, returning stolen money, or community service”. Restorative justice involves both victim and offender and focuses on their personal needs. In addition, it provides help for the offender in order to avoid future offences. It is based on a theory of justice that considers crime and wrongdoing to be an offence against an individual or community, rather than the state. Restorative justice that fosters dialogue between victim and offender shows the highest rates of victim satisfaction and offender accountability.

I think about how I have applied, in a small way, some of the lessons I have learned from practicing this process. For several years I have worked alongside a descendant of a family who enslaved some of my ancestors, piecing together our shared history. She took the brave step of linking to my family pages, something that many white people in the genealogy community won’t do. I also accepted the apology of an elderly member of my grandmother’s family-the family that kicked her out and scratched her out of the family Bible when she married a black man. I now communicate with cousins I never knew. Daily, I remember to rise and thank the Native Americans on whose land I now live. Small things, perhaps seemingly unimportant, but they buttress me, and give me the strength to continue to reach out and attempt to forge coalitions no matter how uncomfortable they may be.

The concept of restorative justice is being expanded into many other areas, like this project that deals with families, and bullying.

Angela Davis addresses this when addressing prison abolition, and changing from a system that is simply punitive.

I’ll close with Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, where young people of all colors can now weave a musical salute to how far they have come.

The song was the official anthem for the African National Congress during the apartheid era and was a symbol of the anti-apartheid movement. For decades during the apartheid regime it was considered by many to be the unofficial national anthem of South Africa, representing the suffering of the oppressed. In 1994 after the fall of apartheid, the new President of South Africa Nelson Mandela declared that both “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” and the previous national anthem, “Die Stem van Suid-Afrika” (“The Call of South Africa”) would be national anthems. While the inclusion of “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” celebrated the newfound freedom of many South Africans, the fact that “Die Stem” was also kept as an anthem even after the fall of apartheid, signified to all that the new government under Mr Mandela respected all races and cultures and that an all-inclusive new era was dawning upon South Africa. In 1996, a shortened, combined version of the two anthems was released as the new national anthem of South Africa under the constitution of South Africa.

Nkosi sikelel’ iAfrika

Maluphakanyisw’ uphondo lwayo,

Yizwa imithandazo yethu,

Nkosi sikelela, thina lusapho lwayo.Morena boloka setjhaba sa heso,

O fedise dintwa le matshwenyeho,

O se boloke, O se boloke setjhaba sa heso,

Setjhaba sa South Afrika — South Afrika.Uit die blou van onse hemel,

Uit die diepte van ons see,

Oor ons ewige gebergtes,

Waar die kranse antwoord gee,Sounds the call to come together,

And united we shall stand,

Let us live and strive for freedom,

In South Africa our land.

cross-posted from Daily Kos

15 comments