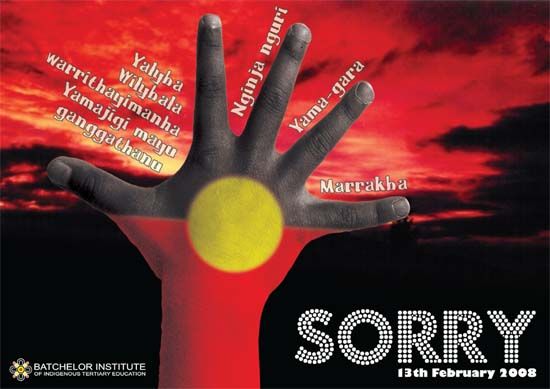

One of three posters produced by Batchelor Press/Batchelor Institute to commemorate the day Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apologised to the stolen generation (13th February 2008)

On May 26th, each year since 1998, people in Australia come together for National Sorry Day events, and on February 13th to commemorate the National Apology to the Stolen Generations of Indigenous Australians given by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on behalf of the government and the nation.

This is part two in a series of articles examining national apologies to those who suffered egregious wrongs, pain, suffering and death at the hands of governments and people, and an examination of national efforts towards reconciliation and the righting of wrongs. Last Sunday I examined the recent apology speech by Australian PM Julia Gillard.

I was, and am, moved by the righting of wrongs inflicted on minority populations or the powerless by those in power. I am also interested in how efforts toward reconciliation and reparation play out in countries other than the U.S.

I admit that my whole life I have waited for the United States to undertake something similar. An apology to Native Americans for historical ethnocide and removal and for the ongoing injustices our nation’s first people suffer each day. An apology for slavery and the affects of that foundational injustice that still has a negative systemic impact on our citizens of African descent and others who face racism and xenophobia.

We as a nation have much to say we are sorry for, and to correct.

As a descendant of Africans who were enslaved here, of assimilated or erased tribes, and yes, also of slave holders and Indian killers, I dream of this happening right here at home.

I am still waiting.

And so I turn to Australia, from where I feel an odd sense of kinship with Australian Aborigines, for they are dubbed blacks (like me) and were in some cases, like in Tasmania, wiped out almost completely, while others had the land with which they have a deep spiritual kinship appropriated and their children stolen which parallels the ongoing fate of my Ndn sisters and brothers here.

In 2007, the Prime Minister of Australia announced he would be issuing an apology to Australian aborigines. He kept his promise, and on February 13, 2008 delivered the following speech to the nation.

That today we honour the Indigenous peoples of this land, the oldest continuing cultures in human history.

We reflect on their past mistreatment.

We reflect in particular on the mistreatment of those who were Stolen Generations-this blemished chapter in our nation’s history.

The time has now come for the nation to turn a new page in Australia’s history by righting the wrongs of the past and so moving forward with confidence to the future.

We apologise for the laws and policies of successive Parliaments and governments that have inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians.

We apologise especially for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country.

For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry.

To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry.

And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.

We the Parliament of Australia respectfully request that this apology be received in the spirit in which it is offered as part of the healing of the nation.

Archie Roach, one of Australia’s most beloved singer-songwriter-activists, tells the tale in his acclaimed “Took The Children Away,” from firsthand experience.

This story’s right, this story’s true

I would not tell lies to you

Like the promises they did not keep

And how they fenced us in like sheep.

Said to us come take our hand

Sent us off to mission land.

Taught us to read, to write and pray

Then they took the children away,

Took the children away,

The children away.

Snatched from their mother’s breast

Said this is for the best

Took them away.The welfare and the policeman

Said you’ve got to understand

We’ll give them what you can’t give

Teach them how to really live.

Teach them how to live they said

Humiliated them instead

Taught them that and taught them this

And others taught them prejudice.

You took the children away

The children away

Breaking their mothers heart

Tearing us all apart

Took them away

This video shows some of the faces of those listening to the speech.

It is a testament to the power of a government saying “we are sorry.”

A view of people watching PM Rudd’s speech on big screens,apologising to the Stolen Generations. February 13, 2008

The history leading up to a possible new beginning for Australian Aboriginal peoples is a long one. From first contact by Europeans, and settlement, the road was littered with a series of massacres . The last known documented massacre took place in Coniston in 1928, which was portrayed in the film Coniston.

Link to the trailer.

There was no real national policy about Aboriginal treatment-Australia had only become a nation in 1901.

By the 1930’s there were government policies in place and none of them benefited Aborigines.

In 1937, the Commonwealth Government held a national conference on Aboriginal affairs which agreed that Aboriginal people ‘not of full blood’ should be absorbed or ‘assimilated’ into the wider population. The aim of assimilation was to make the ‘Aboriginal problem’ gradually disappear so that Aboriginal people would lose their identity in the wider community.

Protection and assimilation policies which impacted harshly on Indigenous people included separate education for Aboriginal children, town curfews, alcohol bans, no social security, lower wages, State guardianship of all Aboriginal children and laws that segregated Indigenous people into separate living areas, mainly on special reserves outside towns or in remote areas.

Another major feature of the assimilation policy was stepping up the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families and their placement in white institutions or foster homes.

It wasn’t until 1997 that the depredations and impact of the forcible removal policy were really dealt with in a government report.

Two reports were produced:

Formal, 700-page report Bringing them Home and subtitled Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families

Less formal and shorter community guide called Bringing them Home-Community Guide and subtitled “A guide to the findings and recommendations of the National Inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families”.

The report concluded that “indigenous families and communities have endured gross violations of their human rights. These violations continue to affect indigenous people’s daily lives. They were an act of genocide, aimed at wiping out indigenous families, communities, and cultures, vital to the precious and inalienable heritage of Australia”

This didn’t happen without the pressure from a movement. Indigenous people and their allies organized a civil and human rights movement, a land rights movement and a black power and dignity movement.

A key figure in the battle for land rights was Eddie Mabo.

I will not post a photo of him here out of respect for the beliefs of his people, since he is deceased.

The high court ruling which in Australia is often referred to as simply “the Mabo Decision” was one of those pivotal moments in history, which he initiated in 1973.

In May 1982, Eddie Mabo and four other Meriam people of the Murray Islands in the Torres Strait began action in the High Court of Australia seeking confirmation of their traditional land rights. They claimed that Murray Island (Mer) and surrounding islands and reefs had been continuously inhabited and exclusively possessed by the Meriam people who lived in permanent communities with their own social and political organisation. They conceded that the British Crown in the form of the colony of Queensland became sovereign of the islands when they were annexed in 1879. Nevertheless they claimed continued enjoyment of their land rights and that these had not been validly extinguished by the sovereign. They sought recognition of these continuing rights from the Australian legal system. The case was heard over ten years through both the High Court and the Queensland Supreme Court. During this time, three of the plaintiffs including Eddie Mabo died.

On 3 June 1992, the High Court by a majority of six to one upheld the claim and ruled that the lands of this continent were not terra nullius or land belonging to no-one when European settlement occurred, and that the Meriam people were ‘entitled as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of (most of) the lands of the Murray Islands.’

The decision struck down the doctrine that Australia was terra nullius – a land belonging to no-one. The High Court judgment found that native title rights survived settlement, though subject to the sovereignty of the Crown. The judgment contained statements to the effect that it could not perpetuate a view of the common law which is unjust, does not respect all Australians as equal before the law, is out of step with international human rights norms, and is inconsistent with historical reality. The High Court recognised the fact that Aboriginal people had lived in Australia for thousands of years and enjoyed rights to their land according to their own laws and customs. They had been dispossessed of their lands piece by piece as the colony grew and that very dispossession underwrote the development of Australia into a nation.

His life story, and the story of the struggle for land rights (which is ongoing) has been documented in a recent docudrama.

In 1973 Eddie ‘Koiki’ Mabo was shocked to discover that the ownership of the land his ancestors had passed down on Murray Island in The Torres Strait Islands for over 16 generations, was not legally recognised as theirs.

Rather than accept this injustice, he began an epic fight for Australian law to recognise traditional land rights. Eddie never lived to see his land returned to him, but the name Mabo is known in every household throughout the country.

In January 1992, at only 55, Eddie died of cancer. Five months later the High Court overturned the notion of terra nullius. Underscoring this epic battle is Eddie’s relationship with his wife Bonita. MABO is as much a love story as a document of one man’s fight to retain what he believed was legally his.

In 1972, Aboriginal activists set up a tent embassy:

Late on Australia Day 1972, four young Aboriginal men erected a beach umbrella on the lawns outside Parliament House in Canberra and put up a sign which read ‘Aboriginal Embassy’. Over the following months, supporters of the embassy swelled to 2000. When the police violently dismantled the tents and television film crews captured the violence for the evening news, an outraged public expressed its disgust to the federal government.

This political action was initiated and implemented by Aboriginal activists. The site became known as the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. It was a powerful symbol. The original owners of the land set up an ’embassy’ opposite the parliament, as if they were foreigners. This act showed compellingly the strength of their sense of alienation. They were landless. Their embassy was a tent – a well understood image of poverty and impermanence. Their camp attracted unprecedented support from people across the country who recognised their sense of grievance and made their views known to the government.

Though not without supporters, the occupiers of the tents came into direct confrontation with police and government forces.

In 1982, at the time of the Commonwealth Games, land rights activists staged protests. They labeled the sports event the Stolenwealth Games. Those same activists, with new supporters, are still protesting.

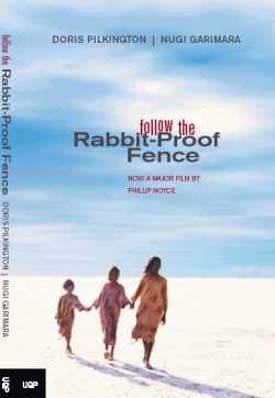

The history and plight of the stolen generations became more widely known, both inside and outside of Oz, due to the publication of Doris Pilkington’s book “Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence.”

Doris Pilkington had spent much of her early life from the age of four at the Moore River Native Settlement in Western Australia, the same facility the book chronicles her mother escaping from as a child. After re-uniting with her family, Pilkington says she did not talk to her mother much, and she was not aware of her mother’s captivity at Moore River, or the story of their escape, until her Aunt Daisy told her the story. Repeating the story at an Aboriginal family history event in Perth, one of the attendees told her he was aware of the story and that the case was fairly well-documented. He gave her some documents and clippings which formed the factual backbone of the story on which Pilkington based a first draft.

She submitted the draft to a publisher in 1985, but was told it was too much like an academic paper, and that she should try her hand at writing fiction. Her first novel, Caprice, A Stockman’s Daughter, won the David Unaipon Literary Award and was published in 1990 by the University of Queensland Press. Pilkington then rewrote and filled out Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence following several years of interviewing her mother and aunt, and it was published in 1996.

The book was made into an award-winning film.

Rabbit-Proof Fence is a 2002 Australian drama film directed by Phillip Noyce based on the book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington Garimara.

Efforts to achieve reconciliation are taking place all across Australia. NGOs and organizations like Reconciliation Australia carry on the process.

Reconciliation Australia is the national organisation promoting reconciliation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian community.

Our vision is for an Australia that recognises and respects the special place, culture, rights and contribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; and where good relationships between First Australians and other Australians become the foundation for local strength and success; and the enhancement of our national wellbeing.

Our programs such as the Indigenous Governance Awards Project and the Reconciliation Action Plans, along with our advocacy and public education work, are about building sustainable frameworks for lasting change in Australia.

Artists and cultural activists are part of that process too.

Ngarraanga (Remember) or Ngarraanga Ngiinundi Yuludarra (Remember Your Dreaming) is Emmas tribute to the Stolen Generations and includes traditional language, written with long time writing partner Yanya Boston. The video was shot at Carriageworks in Redfern in Sydney and features the extraordinary talent of Torres Strait Islander dancer, Albert David, inter-woven with archival footage.

‘murundak’ – songs of freedom’journeys into the heart of Aboriginal protest music following The Black Arm Band, a gathering of some of Australia’s finest Indigenous musicians, as they take to the road with their songs of resistance and freedom.

From the concert halls of the Sydney Opera House to remote Aboriginal communities of the Northern Territory, ‘murundak’ – meaning ‘alive’ in Woirurrung language – brings together pioneering singers including Archie Roach, Bart Willoughby and the late Ruby Hunter, and a stellar lineup of emerging Indigenous talent including Dan Sultan, Shellie Morris and Emma Donovan.

Has Sorry Day, reconciliation, winning court cases and activism erased racism from Australia? No. Is Australia moving forward, out of the pits of its history? Yes.

Many of Australia’s aboriginal people still live in poverty, have high rates of unemployment, have low life expectancy, health issues, and suffer from alcoholism and depression. So there is much more work to be done. Reconciliation has engaged more white Australians in the process.

This Sorry Day letter from Queensland organizations is an example.

On 26th May 2012, a full-page open letter to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Queensland was published in the Courier Mail. Signatories to this letter included over thirty Queensland organisations and individuals who, in a combined voice, wished to commemorate National Sorry Day and convey an important message to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander citizens of our State.

In the words of an Aboriginal friend and colleague who sent me a text message on the 26th May, “It was awesome to see that beautiful letter in the paper this morning!” It sure was!

Plans are already in the offing for National Reconciliation Week 2013 from May 27th to June 3rd in schools, and community organizations.

Change takes place one step at a time, and these are, imho, good steps.

(Cross-posted from Daily Kos)

12 comments