Growing up, I loved the stories I read about Harriet Tubman, and her brave forays into slave territory to spy and lead others to freedom. At the time, there were a few other black women like Sojourner Truth, whose stories were written about as tales of resistance and I knew family legends that were passed down about my own strong enslaved ancestors, but the library seemed to be pretty bare of reading material on other black women who had resisted enslavement.

That is beginning to change, and I can only hope we will see more in the years to come.

If you have not yet read the historical novel The Secrets of Mary Bowser, I strongly suggest you add it to your reading list. Yes it is fiction, but fiction grounded in historical research by author Lois Leveen, who discusses her book in an excellent NY Times piece, A Black Spy in the Confederate White House.

Mary Bowser, born into slavery in Virginia sometime around 1840, was, alternately, a missionary to Liberia, a Freedmen’s school teacher – and, most amazingly, a Union spy in the Confederate White House.Her wartime career is all the more astounding because her espionage depended on the very institution that was meant to subjugate her. Chattel slavery was predicated on the belief that blacks were innately inferior – leaving a slave woman not so much above suspicion as below it – yet Bowser demonstrated the value of black intelligence, in every sense of the term. But the truth about the woman who went from slave to spy is fascinating and revealing precisely because it remains incomplete.

I first became aware of Mary Richards Bowser’s extraordinary exploits, when Vertamae Grosvenor, seen here in a photograph taken in the Jefferson Davis dining room, reported on her in a piece for NPR.

The Spy Who Served Me: A Tale of Espionage from the ‘White House’ of Jefferson Davis

Vertamae Grosvenor was looking at the history of servants at the White House in Washington and came upon a story of espionage at another executive mansion — in Richmond, Va. It happened during the Civil War. Here is Grosvenor’s essay for Morning Edition:

I started researching the history of servants in one White House and came upon a tale of intrigue and espionage inside another one. It happened during the Civil War.

Grosvenor talks about Mary Bowser and her former owner Elizabeth Van Lew:

Mary Bowser was born into slavery in the household of John Van Lew, a wealthy hardware merchant in Richmond, Va. Van Lew’s daughter Elizabeth freed Mary Bowser and all her father’s other slaves after he died. Elizabeth Van Lew, who never married, was known as an eccentric who sometimes walked down the streets of Richmond, head bent to one side, holding conversations with herself. Some called her “Crazy Bet”.

“Crazy Bet” Van Lew inherited a lot of money and her father’s society connections. She used some of the money to send her former slave Mary Bowser to school in Philadelphia and later Elizabeth used her connections to get Mary Bowser a servant job in President Jefferson Davis’ Confederate White House.

Now, thanks to the research of author Leveen, more tantalizing details have come to light.

Bowser began her life as property of the Van Lews, a wealthy, white Richmond family. Although her exact date of birth is unknown, on May 17, 1846, “Mary Jane, a colored child belonging to Mrs. Van Lew,” was baptized in St. John’s, the stately Episcopal church for which the elegant Church Hill neighborhood of Richmond is named, and in which Patrick Henry delivered his 1775 “give me liberty or give me death” speech. It was extremely rare for enslaved or free blacks to be baptized in this church. Indeed, other Van Lew slaves received baptism at Richmond’s First African Baptist Church, indicating that Mrs. Van Lew, the widowed head of the household, and her daughter Bet singled out Mary for special treatment from an early age.

Some time after being baptized, Mary was sent north to be educated, although it is unclear precisely when or where she attended school. In 1855, Bet arranged for the girl, then using the name Mary Jane Richards, to join a missionary community in Liberia. According to Bet’s correspondence with an official of the American Colonization Society, however, the teenage Mary was miserable in Africa. By the spring of 1860, she returned to the Van Lew household, and eventually to St. John’s Church, where, on April 16, 1861 – the day before the Virginia Convention voted to secede – Wilson Bowser and Mary, “colored servants to Mrs. E. L. Van Lew,” were married.

Leveen has also found that Mary Richards/Bowser told her own tale:

But the former spy had already told her own story, publicly and privately, in the period immediately following the war, as recent research has revealed. Nevertheless, her own accounts don’t amount to straightforward autobiography, because she deliberately concealed or altered aspects of her life, as she carefully constructed her own identity and positioned herself in relation to the larger black community.

On Sept. 10, 1865, The New York Times published a notice for a “Lecture by a Colored Lady”:

Miss RICHMONIA RICHARDS, recently from Richmond, where she has been engaged in organizing schools for the freedmen, and has also been connected with the secret service of our government, will give a description of her adventures, on Monday evening, at the Abyssinian Baptist Church.

There can be little doubt that this was Bowser. And yet, as the use of a pseudonym suggests, she was consciously constructing a public persona. Reporting on the talk, the New York-based newspaper the Anglo African described Richards as “very sarcastic and … quite humorous.” The audience might have been most amazed by her description of collecting intelligence in the Confederate Senate as well as the Confederate White House, and aiding in the capture of rebel officers at Fredericksburg, Va. But her acerbic wit shone best when she described her time in Liberia, where “the Mendingoes … never drink, lie, nor steal,” making them “much better than the colored people are here.” (She concluded by admonishing young people to pay less attention to fashion and more to education.)

There is only one unconfirmed picture of Mary Bowser.

She is portrayed here by actress Vernice Jackson.

In 1995, Bowser was inducted into the U.S. Army Intelligence Hall of Fame. While researching more about Bowser, I wound up (much to my surprise) on the CIA website, where I found “Black Dispatches: Black American Contributions to Union Intelligence During the Civil War“, by P.K Rose.

It was there I learned of another Mary.

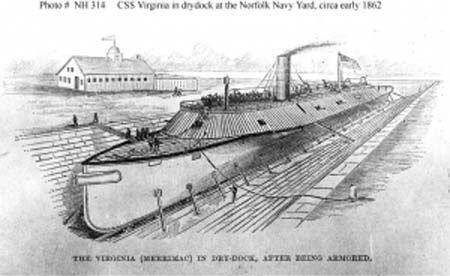

Mary Touvestre, a freed slave, worked in Norfolk as a housekeeper for an engineer who was involved in the refitting and transformation of the USS Merrimac into the Virginia, the first Confederate ironclad warship. Overhearing the engineer talking about the importance of his project, she recognized the danger this new type of ship represented to the Union navy blockading Norfolk. She stole a set of plans for the ship that the engineer had brought home to work on and fled North. After a dangerous trip, she arrived in Washington and arranged a meeting with officials at the Department of the Navy.

The stolen plans and Touvestre’s verbal report of the status of the ship’s construction convinced the officials of the need to speed up construction of the Union’s own ironclad, the Monitor. The Virginia, however, was able to destroy two Union frigates, the Congress and the Cumberland, and run another, the Minnesota, to ground before the Union ironclad’s arrival. If the intelligence from Touvestre had not been obtained, the Virginia could have had several more unchallenged weeks to destroy Union ships blockading Hampton Roads and quite possibly open the port of Norfolk to urgently needed supplies from Europe.

I am hoping that an enterprising researcher/writer will take on the task of fleshing out more details of her story as well.

Cross-posted from Black Kos

22 comments