A Day of Remembrance: the Orangeburg Massacre

Today, Feb the 8th is the anniversary of what took place at South Carolina State University (SCSU) in Orangeburg in 1968. Three young men lost their lives, 28 were wounded (most shot in the back) a pregnant young woman lost her baby and a young activist Cleveland Sellers was railroaded into jail.

These are the young men who were murdered:

Henry Smith, Delano Middleton,and Samuel Hammond Jr.

Delano Middleton, an Orangeburg High School student, lays wounded on the campus of South Carolina State College on Feb. 8, 1968. AP

You all know about Kent State. Some of you may even know about Jackson State which took place 14 days after Kent State, leaving 2 students dead and 12 wounded.

Some of you may not have been alive at the time.

In 1968 I was a student at another historically black university, Howard University, where two months later students would stage the first major takeover of an HBC campus. We were engaged in community organizing, the Civil Rights Movement and against the Vietnam War. We knew that what had happened in Orangeburg could have happened to any of us.

We also knew that there would be no justice for the slain, no punishment of the murderers, and little attention would be paid in the national media to the plight of those in Orangeburg, or for that matter to what was done to black students anywhere.

That knowledge did not stop those involved from demanding justice. The survivors and their loved ones continue to tell the tale. Each year more people learn the truth about Orangeburg.

Reporter Frank Beacham sets the scene:

The setting was South Carolina State College (now University), one of two small black colleges located in Orangeburg, a mostly white, ultra-conservative community of 20,000 located about forty miles southeast of Columbia. Although S.C. State College and nearby Claflin University—with a combined enrollment of about 2,300 students—insured a substantial well-educated black population in the town, a social wall continued to divide the races. In 1968, white Orangeburg was a hotbed of segregationist radicalism—a center for organizations resisting the social change sweeping the South.

The S.C. State campus, made up of students from mostly poor and middle class black families, was a cultural world apart from the white neighborhoods surrounding it. The students had a rich legacy of civil rights activism, and, in 1968, there remained an undercurrent of tension over the second-class treatment the college was receiving from the state government. However, the conflict that led to the Orangeburg massacre began at a bowling alley. John Stroman, a black S.C. State senior from Savannah, Georgia, had a passion for bowling. All Star Bowling Lanes, the only bowling facility within forty miles of the campus, refused to admit black patrons. Its owner, Harry Floyd, believed that the presence of black bowlers would hurt his business. His stubborn refusal to serve black customers—including students from the local colleges—elevated the bowling establishment to a highly visible symbol of the remaining segregation in Orangeburg. A group of students, organized by Stroman, decided to stage a protest.

He goes into detail about not only the lead-up to the events, but to the whitewash that followed. Wish that I could copy the entire document here, but please go give it a full read.

An act of racism in a small college town leads to peaceful protest by frustrated black students. The governor, elected on a platform of racial moderation, responds with a vast show of armed force. Each side misreads the other, escalating the conflict. Then, in a peak of emotional frenzy, nine white highway patrolmen open fire on the students. In less than ten seconds, the campus turns into a bloodbath.Over four days in early February, 1968, this scenario played out in Orangeburg, South Carolina. On the final day, three black students were killed and 27 others wounded when the lawmen sprayed deadly buckshot onto the campus of South Carolina State College. Most of the students, in retreat at the time, were shot from the rear—some in the back, others in the soles of their feet. None carried weapons.

The killings occurred in a southern state heralded for its record of nonviolence during the civil rights era. In attempt to preserve its carefully-cultivated image of racial harmony, a web of official deceptions was created to distort the facts and conceal the truth about what happened in Orangeburg. The state’s young governor, Robert E. McNair, claimed the deaths were the result of a two-way gun battle between students and lawmen. The highway patrolmen insisted their shooting was done in self-defense—to protect themselves from an attacking mob of students. At first, the state’s cover-up worked. Later, it unraveled. Now, after 40 years, the story of Orangeburg continues to simmer unresolved in a twilight zone of blame and denial.

A film was made to document this history:

Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968. (trailer)

Juan Gonzalez,from Democracy Now, who was an student activist at Columbia University during those days, and who in the following year(1969)became a leading member of the Young Lords Party did a retrospective:

Orangeburg Massacre — Survivors Tell Their Stories

Why don’t we all know this history? Here’s one answer:

Remembering the Orangeburg Massacre – South Carolina State University

Although historians devote attention to the student protests at the University of California – Berkeley and Columbia University, S.C. State is often ignored. Four students at Kent State University were killed May 4, 1970, two years after the incident at S.C. State, yet it gained far more attention and is ofte

n referred to as the first time protesting students were fired upon.The Orangeburg Massacre is often left out of the history books. Advocates stress that this legacy must be told. “S.C. State didn’t get the same attention as Kent State because our students were Black. It wasn’t newsworthy,” says Thomas Kennerly of Columbia, S.C.

Over the years, in South Carolina those who do remember have made sure to keep the events alive, for each generation of students who stand on the shoulders of those who died.

Dr. Cleveland Sellers, one of the survivors and the only one imprisoned as a result has never stopped being a living testimony to that history.

Cleveland Sellers was one of the first students to leave Howard University to work full time for civil rights and voter registration in the early 60’s. He is currently the President of Voorhees College.

Orangeburg Massacre 40th Commemoration Ceremony

Cleveland Sellers speaks

Had Cleveland Sellers been killed that night in Orangeburg, he would not have lived to marry and raise a family. He would not have had three children. The youngest, his son Bakari, grew up to become the youngest member of the South Carolina Legislature.

We will never know what the lives of Henry Smith, Delano Middleton,and Samuel Hammond Jr would have been. They lie in graves. Silenced.

It was not until 1993 that Cleveland Sellers received a “pardon” from the State.

In 1968, Cleveland Sellers was arrested in connection with what would become known as the Orangeburg Massacre. Police allege Sellers instigated a confrontation between the law officers and the protesters, resulting in the death of three student protesters. Sellers, a former SNCC chairman, was convicted and spent several years in prison. In 1993 Sellers was pardoned by the Pardon Board of the State of South Carolina. The pardon freed Sellers to continue his academic career unimpeded by a felony record.

In 2008, the Post and Courier did a 4-part series on Dr. Sellers.

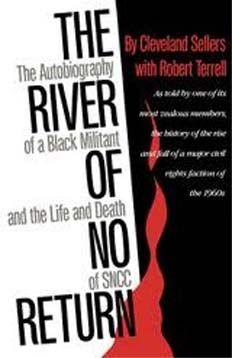

I would suggest that you also read his book:

The River of No Return: The Autobiography of a Black Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC

Beacham closes his reportage with The Legacy of the Orangeburg Massacre, telling the story of young Bakari Sellers.

In 2006, when he decided to run for South Carolina’s legislature against an 82-year-old white incumbent seeking his 25th year in office, Bakari was given little or no chance of victory. Yet, with the help of friends and fellow law students, he trudged door-to-door, knocking on 2,600 of them from morning until dark. The son of Cleveland Sellers pulled a major upset, winning the election by a margin of 1,954 to 1,591 votes. “It was a referendum on change,” Bakari said. “It was about hope. My election has brought hope to a lot of people.”

After the election, Bakari exploded to public attention—drawing public praise from national leaders that included Sen. Barack Obama, Sen. Hillary Clinton, former President Bill Clinton, and Rep. James Clyburn, the Democratic Majority Whip in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was identified as one to watch in the future. Though his campaign themes were targeted to better education, improved care for the elderly, and a promise to help his community out of a lingering economic depression, it was impossible for the residents of this poverty-stricken region not to see a determined young man carrying the torch for a legendary father and his contributions to America’s civil rights movement. Unlike Robert McNair’s restrained “member of the club” conservatism in the legislature, Bakari Sellers vowed to enter the white-dominated body “kicking, yelling and screaming” against the injustices that have long plagued his poor constituents. His people, victims of South Carolina’s paternalistic politics, had waited long enough for real change.

One of Bakari’s first chores was to call for, after almost four decades, a formal investigation of the Orangeburg Massacre. As Rep. Sellers, he sponsored a joint resolution that was introduced in the House of Representatives on March 29, 2007 to create a committee to review the events of that day and report to the General Assembly and the governor. Unlike his African-American contemporaries who have fled the poverty and lingering racism of rural, black South Carolina, Bakari, a 2005 graduate of Morehouse College, chose to stay home and “be part of something larger than me.” That value, he readily admitted, was a key component in his unusual upbringing. For, in addition to his mother and father, his mentors were some of America’s most prominent civil rights leaders.

Here is an interesting interview with Sellers:

Bakari Sellers interviewed by Julian Bond: Explorations in Black Leadership Series

So let us have a moment of silence here today For those who died, and for those who will carry the struggle forward.

Those who forget are doomed to repeat.

We must ensure that we remember.

cross posted from Black Kos

54 comments