Driving in my car on the way to school, I listen faithfully to my local Public radio station WAMC, Northeast Public Radio, which I also listen to at home via computer. They have just finished a major fund-drive, which amazingly in this time of economic crisis raised more money than ever, fueled by those listeners elated by the election of President Barack Obama, and the station’s liberal-left positions.

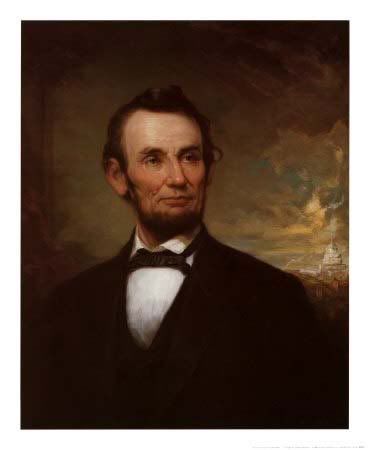

In honor of the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth the station has launched a 15 part series of interviews with a majority of historian scholars on Lincoln, starting yesterday with Harold Holtzer.

2/9 – Harold Holzer – The Lincoln Anthology : 85 Writers on His Life and Legacy From 1860 Until Now. Holzer has authored, coauthored, and edited twenty-two books on Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, including The Lincoln Image, Lincoln Seen and Heard, Dear Mr. Lincoln: Letters to the President, Lincoln as I Knew Him, and Lincoln on Democracy.

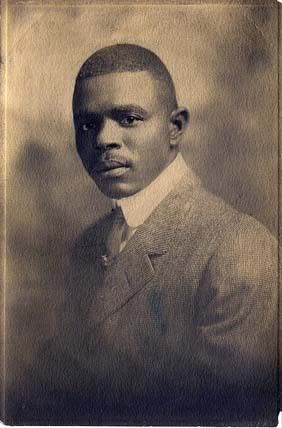

I have mixed feelings about Abraham Lincoln. My grandfather, George S. Oliver was a staunch Republican, proudly proclaiming membership in “the party of Lincoln”. As the child of former slaves, born in Nashville Tennessee in 1875 he became part of a movement of blacks to Kansas known as the Exoduster migration.

He always voted, he saw himself as “a race-man”, staunch supporter of black rights and also of unions; he also married to a white woman from Kansas, my grandmother.

One of my earliest memories was my trip to the Lincoln memorial with my grandparents. Somehow my memories of my grandfather, who died in 1955 when I was 8 years old are intertwined.

It wasn’t until I grew older, and began to research slavery, the Civil War, and reconstruction that I learned of Lincoln’s varying opinions on “Negro’s” and “the colored race”.

I remember a leftist teacher in High School challenging Lincoln’s role as The Great Emancipator”, by providing some of the following quotes and information about Lincoln’s position from Lincoln, which I am taking from an article “The ‘Great Emancipator’ and the Issue of Race”, by Robert Morgan:

Between late August and mid-October, 1858, Lincoln and Douglas travelled together around the state to confront each other in seven historic debates. On August 21, before a crowd of 10,000 at Ottawa, Lincoln declared:17

I have no purpose directly or indirectly to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.

He continued:

I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and black races. There is physical difference between the two which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position.

Many people accepted the rumors spread by Douglas supporters that Lincoln favored social equality of the races. Before the start of the September 18 debate at Charleston, Illinois, an elderly man approached Lincoln in a hotel and asked him if the stories were true. Recounting the encounter later before a crowd of 15,000, Lincoln declared:18

I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races; I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.

He continued:

I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I, as much as any other man, am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.

Society of Friends member and author Henry Wilbur wrote

President Lincoln’s Attitude towards Slavery and Emancipation: With a Review of Events before and since the Civil War

concluding:

What must be the right solution of the race situation? What hope is there that fundamental justice will be done the negro? In the first place, a re-education of public opinion regarding the proscribed race is necessary. The public conscience, especially in the North, must be aroused. That absolutely false reasoning which measures the worth and possibilities of the whole race by the morally bad and economically shiftless negro men and women should be corrected. The negro’s possibilities must be measured as they are for any other race, by the best and most successful among them, and not by the worst and worthless.

In the second place, the supposition that the socalled weaker race was made inferior by the Creator that its members might become and continue menials for the so-called superior race needs to be shown up as a monstrous charge of injustice against the Almighty. Such a conclusion leads to the flippant assertion that the negro must be “kept in his place.” That, of course, means at the bottom and under the absolute control of the white man. As a matter of fact, any place is the negro’s which he can fill, and especially if he can fill it as well or a little better than anybody else. Any plan which provides a fixed class and an unalterable condition for any set of men and women, such condition to pass from father to son, is against the spirit of modern civilization and, if attempted, will provide trouble for society at large in its efforts to work out the plan.

In 2007, Northern Illinois University Press published a collection of articles, edited by Brian R. Dirck, entitled Lincoln Emancipated; The President and the Politics of Race

Abraham Lincoln has long been revered by blacks and whites alike as the “Great Emancipator.” In recent years, however, this image has come under assault by scholars who question Lincoln’s commitment to racial equality and who assert that he was in fact, as Frederick Douglass once noted, the “white man’s president.” Such arguments challenging deep-seated assumptions about our nation’s beloved leader demand serious investigation.

What personal beliefs did Lincoln hold about the inherent differences or similarities between blacks and whites? How did his vision for race relations change as a result of the Civil War? What political, legal, and cultural circumstances prompted him to issue the Emancipation Proclamation? And in what ways have Americans chosen to remember Lincoln’s legacy? Does he truly deserve his fame as the “Great Emancipator?”

In this volume, seven historians attempt to answer these critical questions. Kenneth J. Winkle analyzes the racial climate of the early nineteenth-century Midwest in order to place Lincoln’s views in co

ntext. Kevin R. C. Gutzman discusses the influence of Thomas Jefferson’s racial politics upon Lincoln; and James N. Leiker scrutinizes Lincoln’s attitudes toward Native Americans, Asians, and Hispanics as well as toward blacks. Phillip S. Paludan and Brian Dirck describe Lincoln’s tortured deliberation over emancipation, while Dennis K. Boman uses Missouri as a case study of the president’s delicate handling of this explosive issue. By tracing the changes in Lincoln’s proposals for the future of liberated slaves, Michael Vorenberg argues that, despite what many Americans today would consider limitations, Lincoln demonstrated a remarkable open-mindedness and capacity for growth.

As the nation launches massive Lincoln celebrations, and events and as people reflect on his presidency and legacy, and as another Senator from Illinois now sits in the White House, I take time out to think about my granddad. I wonder what he would think of this today? Doubtful he would be a Republican, had he lived. Would he still honor Lincoln. Probably.

Do I?

I don’t know the answer to that. What I do know is the man was not perfect. He lived in a different era. Will I ever think of him as “The Great Emancipator”. No. Will I honor his role in shepherding this country through the Civil War – yes.

What do you think of Lincoln?

12 comments