The Battle of Pea Ridge was among the largest and most decisive U.S. Civil War battles fought west of the Mississippi River. For two days, over 26,000 soldiers clashed in northwestern Arkansas in a battle that would decide the fate of Missouri. Confederate Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch, a prominent figure in Texas history, perished in the fighting at Leetown, sparking a series of disasters that ensured Union control of a vital strategic hub for the remainder of the war.

Andy Thomas, Two Generals Die, oil on canvas, Pea Ridge National Military Park, Pea Ridge, Arkansas.

Immortalized in a song by Steve Earle, McCulloch’s story and many connections to some of the most significant events in American history well illuminate the trials of young and growing nation who came to be at war with itself.

Author’s Note: It will become quickly obvious that this was written with a professional format in mind. I’m not so great with html coding, so I didn’t bother with links for the individual citations. I am happy to provide the full list of references, upon request.

Grammy™ Award-winning singer-songwriter Steve Earle was born in Fort Monroe, Virginia on January 17, 1955, but grew up and spent much of his youth near San Antonio, Texas (“Steve Earle”, n.d.). In 1995, Earle released an acoustic studio album entitled Train a Comin’, which contains several songs originally written while Earle was a young troubadour in his late teens and early twenties. Earle’s gift for story telling is unmistakably evident in the song ‘Ben McCulloch’, a narrative ballad that traces the exploits of Confederate Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch-as told by a foot soldier under his command in the ‘Texas Infantry’. In general, if not always in the specific, the exploits that comprise McCulloch’s Civil War service are broadly enshrined within the lyrics of Earle’s song, though they only hint at the incredible story of the man who met his end in the pivotal Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in 1862.

Benjamin McCulloch

The fourth son of a dozen children, Ben McCulloch was born in Rutherford County, Tennessee, on November 11, 1811, and went on to become an accomplished hunter and trapper, companion to frontiersman and folk hero Davy Crockett, feared Indian fighter, respected law man, representative to the legislatures of both the Republic and State of Texas, and brigadier general in the Army of the Confederate States of America (“Ben McCulloch Biography”, n.d.).

The McCulloch Family

The McCulloch family, of Scotch-Irish descent, had been both politically influential and prosperous in colonial North Carolina (Cutrer, 2013). Though the family had lost much of its wealth as a result of the Revolutionary War, Ben’s father Alexander McCulloch still inherited a sizable fortune, but he proved financially injudicious. Ben’s uncle once said of Alexander, “… he was not an economist, and loved to spend money on his friends” (Rose, 1958).

Despite his weaknesses in managing the family wealth, Alexander McCulloch was a notable man: educated at Yale, he served with distinction under future president Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812 alongside notables like Davy Crockett and Sam Houston. Known as a kind and generous woman, Benjamin’s mother, Frances LeNoir was the daughter of a prominent Virginia planter and slave owner (Cutrer, 2013; “Veteran Biographies”, 2012). Like many on the western frontier, the McCulloch family relocated often, making homes in various parts of North Carolina, Alabama, and Tennessee between 1812 and 1830 (Rose, 1958).

“A Wild, Daring Lad”

In mid-19th century Tennessee, rural youth typically occupied much of their time tending to chores about the family farm, though frequently spent whatever free time afforded them on exploring the woods, hills, and forests in search of game (“Ben McCulloch Biography”, n.d.; Rose, 1958). In a September 7th, 1861 biography published in Harper’s Weekly, young Benjamin McCulloch was characterized as “always a wild, daring lad; most of his youth was spent in hunting bears and other wild animals” and as having “took to a trapper’s life” as a young man (“Ben McCulloch Biography”, n.d.).

Young Ben proved to be a natural and adept outdoorsman, with a sense of direction keen enough that Rose (1958) notes,

“…though the sun might be obscured, or the North Star hid behind clouds, [he] never was at a loss as to the proper course to be pursued, and not infrequently was he appealed to by hunters older than himself to lead the way home.”

Figure 1. Benjamin McCulloch. Reprinted from The History Press Blog, Retrieved from http://www.historypressblog.ne…

The many skills honed in the wilds of the western frontier would prove useful in the coming years, particularly in his roles as surveyor, officer of the law, and military commander.

“Educated Gentlemen”

While a few of Ben McCulloch’s older brothers briefly attended school taught by Tennessee neighbor and family friend Sam Houston, Ben himself received no formal education save that which he acquired reading and exploring of his own volition. According to Rose (1958) Ben’s education was largely self-acquired, having…

“…received at home a knowledge of the rudiments, when their own good sense and thirst for knowledge led them to explore the various repositories of information which, in the shape of books bound by the hands of man, and in the hidden chapters of Nature’s volume, attracted their attention; and certain it is, at least, that both Generals Ben and [his brother] Henry E. McCulloch were educated gentlemen.”

Unlike many generals who served during the Civil War, McCulloch did not receive formal military training prior to the outbreak of the war between North and South, save the direct experience he gained serving in the Texas Revolution, the Mexican War, and as a Texas Ranger. (“Benjamin McCulloch”, 2013).

Amongst Legends

When the McCulloch family settled at last near Dyersburg, Tennessee young Benjamin was deeply influenced by both Sam Houston and Davy Crockett, who were among the family’s closest neighbors and most trusted friends (“Benjamin McCulloch”, 2013). Both men had served with Ben’s father in the War of 1812, and would become companions and powerful role models for young Ben McCulloch (Rose, 1958). Ultimately, the fate of all three would become entwined with the Republic of Texas, and profoundly shape the history of the state.

Deep in the Heart

By 1827, Davy Crockett had become a politician of some renown via his representation of Tennessee in the U.S. Congress, but by 1835 he had been unseated twice and, disgusted with politics, reportedly proclaimed: “You can all go to Hell and I’m going to Texas” (Bartlett, 1991). True to his word, Crockett headed for Mexican-controlled Texas. Before long, Ben McCulloch would follow and find himself face to face with the Texas War for Independence, and become associated with a number of other exploits and endeavors that would shape both the history of the state and the nation.

Almost the Alamo

Still in his early twenties, McCulloch had worked as a muleskinner, tried his hand at mining in Wisconsin, rafted goods to and from New Orleans, and continued to serve many of the needs associated with family farm in Tennessee (Rose, 1958). Like both Houston and Crockett, McCulloch felt an affinity with the colonists in Texas, as a great many of them were Tennesseans.

It was arranged that McCulloch and his younger brother Henry meet with Crockett at Nacogdoches on Christmas Day of 1835, but their arrival was delayed when McCulloch took ill with the measles and was forced to stop and convalesce (Cutrer, 2013). Fatefully, the sickness saved his life. Crockett waited for the McCulloch’s that Christmas Day, but when the brothers failed to rendezvous with him, he rode on to San Antonio without them (Haile, 2012).

The measles had delayed Ben McCulloch long enough that, by the time they reached San Antonio, the thirteen day siege at the Alamo was over, and his idol Davy Crockett lay dead. Leaving the smoldering Alamo and San Antonio behind, McCulloch caught up with the remnants of Houston’s retreating army, joining in earnest the effort to win independence for Texas (West, 2008). McCulloch would go on to play a critical role in April of 1836, when he served under Houston at the decisive Battle of San Jacinto, manning one of the famed ‘Twin Sisters’ cannons (Cutrer, 2013). Firing glass, horseshoes, and anything else they could find, McCulloch was key to delivering the final defeat to Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna (West, 2008).

Lone-Star Statesman

Following in the footsteps of his mentors Houston and Crockett, and boosted by the fame earned as a hero of the Texas Revolution, McCulloch took to political life in 1839 when he was elected to serve in the legislature for the then independent Republic of Texas (Cutrer, 2013; Rose 1958). Whatever his political acumen, McCulloch’s most notable ‘achievement’ as a legislator may have been a duel with political adversary Reuben Ross, in which McCulloch received a wound that partially crippled his right arm (Cutrer, 2013; West, 2008). Ross was later gunned down in a duel with Ben’s brother, Henry McCulloch. After the annexation of Texas into the Union, Ben McCulloch returned to elected office-this time to the newly formed state legislature (West, 2008).

Texas Rangers and the Mexican-American War

In 1838, while employed by the Republic of Texas as a surveyor, McCulloch joined a company of Texas Rangers under the command of Jack Hays, where he soon established his reputation as a scout, solider, and commander. McCulloch proved invaluable at the August 12, 1840 Battle of Plum Creek, and in 1842 his reconnaissance of enemy positions played a critical role in recapturing San Antonio from Mexican raiders (“Benjamin McCulloch”, 2009).

When war between the United States and Mexico broke out in 1846, many Texas Rangers were drawn into Federal service. McCulloch raised a company of his own to command within the larger First Regiment of Texas Mounted Volunteers, and when his aptitude for reconnaissance became apparent, he was appointed chief of scouts directly under Gen. Zachary Taylor (Cutrer, 2013; West, 2008). McCulloch continued to build his reputation as an able officer at the battles of Monterey and Buena Vista (Cutrer, 2013). By the time the Mexican-American war had concluded, McCulloch had ascended to the rank of Major (Wesbennt, 2008).

Law Man

Restless after the Mexican-American war, McCulloch made for the gold fields of California on September 9, 1849 seeking fortune-and finding none (West, 2008). A year later in 1850, he was being sworn in as the second Sheriff of Sacramento, served his full term, and returned to Texas 1852. Soon after, President Franklin Pierce tapped McCulloch to serve as United States Marshall for the Eastern District of Texas. In 1858, President James Buchanan appointed McCulloch Commissioner to Utah, where he was influential in preventing the eruption of hostilities between the United States government and Brigham Young’s Mormons (“Benjamin McCulloch”, 2009; Cutrer, 2013).

A Moment’s Notice: Civil War

When secession came to Texas, McCulloch was commissioned a colonel and tasked with securing the surrender of all federal posts in the Military District of Texas. His response to theses orders were brief: “to Texans, a moment’s notice is sufficient when their State demands their service” (United States & Scott, 1971). Having raised a force to carry out this mission, McCulloch succeeded in persuading Union General David Twiggs to relinquish the entire federal arsenal and all other U.S. property in San Antonio on February 16, 1861 (Benjamin McCulloch, 2013; Cutrer, 2013). Not a single shot was fired.

Impressed, Jefferson Davis appointed McCulloch to the rank of brigadier general, making him the second-ranking brigadier general in the Confederate Army at that time, and the first general-grade officer to be commissioned from the civilian community (Cutrer, 2013). In this new role, McCulloch was granted command of Indian Territory, established headquarters in neighboring Arkansas, and began to build the CSA’s Army of the West with regiments from Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana, as well as allied Native American groups such as the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Creeks (Cutrer, 2013). In an April 14, 1861 letter to Texas Governor Edward Clark, McCulloch wrote,

“I have to leave in great haste to take comd of the Indian Territory. N. of Texas & S. of Kansas, with two Regs of Mounted men, one from Texas, the other from Ark, one Reg of Infantry from La. & two of Indians, this will protect our northern border…” (“War, Ruin, and Reconstruction”, 2011).

“We signed up in San Antone”

It is sometime during this formational period when the fictional brothers in Steve Earle’s (1995; Appendix) song ‘Ben McCulloch’ ostensibly volunteered to serve under the newly minted Brigadier General McCulloch:

We signed up in San Antone my brother Paul and me,

To fight with Ben McCulloch and the Texas infantry.

Well the poster said we’d get a uniform and seven bucks a week,

The best rations in the army and a rifle we could keep

While McCulloch was certainly recruiting able men during this period, it is unlikely that efforts to muster infantry troops would have met with much success. Texans were horsemen after all, and the recruitment poster to which Earle alludes would probably not have gained the interest of most self-respecting Texans. British Lt. Col. Arthur Fremantle, while travelling through Texas during the war, noted “It was found very difficult to raise infantry in Texas, as no Texan walks a yard if he can help it” (Petersen, 2007).

Calls for volunteers to serve in cavalry units were far more likely to bear fruit, though recruits were typically required to provide their both their own mount and weapons (Petersen, 2007). On June 30, 1861 McCulloch sent the following dispatch from his Headquarters at Fort Smith, Arkansas:

“Men of Texas. Look to your arms and be ready for any emergency! The state of Missouri is almost subjugated. The small force she has in the field is being driven back upon Arkansas. We march today to help and aid them. The Black Republicans boastingly say that they have conquered Missouri and now will overrun Arkansas and Texas. Will you permit it?” (Petersen, 2007).

In any event, an offer of ‘seven bucks a week’ would have been attractive, as a rank of Private would have come with a salary of only $11 per month, and was only increased to $18 per month in June of 1864 (“Soldiers Pay in The American Civil War”, 2002).

McCulloch did publically call for the muster of infantry sometime around August 25th, 1861:

“Citizens of Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana: – …having received instructions from the department at Richmond to increase the force under my command, I will receive and muster into the service of the Confederate States five regiments of infantry from each of the above named states… regiments are to equip themselves with the best arms they can procure…each man will be provided with two suits of winter clothing, and two blankets, also with tents, if they can be obtained” (Rose, 1958).

While this entreaty calls specifically for infantry volunteers, it cannot have been the same as that responded to by the protagonists of Earle’s song, as this request was made after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (where the narrator’s brother was already in service under McCulloch, and killed in action). Further, it is clear that this request makes no provision with respect to the quality of rations or the bestowment of weapons.

“My brother died at Wilson’s Creek”

On, 1861, McCulloch achieved a hard-fought victory under difficult circumstances at Wilson’s Creek, in southwestern Missouri (Cutrer, 2013). After spending a day planning, Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon’s army struck first in a surprise attack, launched early the morning of August 10th. It was McCulloch’s own cavalry unit that received the brutal first blow. Lyon successfully overran the Confederate camps, but found his forces halted by an artillery barrage at what came to be called ‘Bloody Hill’ (“The Battle of Wilson’s Creek”, 2013).

McCulloch rallied the Confederate forces to regroup, stabilized their positions, and tenaciously spent the day mounting three separate assaults on the now pinned-down Union line, which was badly mauled but unbroken throughout the day (Cutrer, 2013; McPherson, 1988). Lyon was killed during the battle, and fearing they could not withstand another assault, Major Samuel D. Sturgis-the highest ranking Union officer still engaged-ordered a prompt retreat of all surviving forces back to Springfield (“The Battle of Wilson’s Creek”, 2013).

Having incurred roughly equivalent casualties, and lacking adequate ammunition and supplies, McCulloch’s Confederates were in no position to pursue the retreating Federals. The victory, though achieved at great cost, gave the Confederacy control of southwestern Missouri, rendering the state an even brighter flashpoint in the war (McPherson, 1988; “The Battle of Wilson’s Creek”, 2013).

“I must have St. Louis”

Both the Union and the Confederacy were keenly aware of the State of Missouri’s strategic role in securing the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio Rivers for commerce, supply, and invasion routes. In late 1861, Missouri was essentially rift by partisans, with Union Federals controlling the northeast and most rail and water routes, and the Major General Sterling Price’s pro-secession Missouri State Guard (to which McCulloch’s units were temporarily attached) firmly holding the southwestern corner of the state (Cutrer, 2013; Shea & Hess, 1992).

Despite Confederate victories in battles at Lexington and Wilson’s Creek, the Missouri statehouse remained loyal to the Union. The Lincoln administration feared the state was tipping toward secession and Major General Henry Halleck, who commanded the Department of the Missouri, urgently sought to break the stalemate (Shea & Hess, 1992). Whoever controlled Missouri gained an important advantage in the war, so Halleck tasked Brigadier General Samuel Ryan Curtis with the removal or destruction pro-secessionist forces in the state.

By February 17, 1862, Curtis had successfully dislodged Price’s Missouri State Guard, and pushed the Confederates into a sustained retreat all the way to the Boston Mountains, some sixty miles inside northwestern Arkansas (Cutrer, 2013; Shea & Hess, 1992). With his supply lines stretched to their limits, Curtis halted his advance through Benton County, Arkansas and gathered his 10,500 troops and associated artillery into a well-fortified defensive position along the northern bluffs overlooking Little Sugar Creek (Cutrer, 2013; Shea & Hess, 1992).

Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn, given control of both Price’s Missouri State Guard and McCulloch’s army in an effort to override the rifting personal and professional conflicts between their commanding Generals, was eager to launch a counteroffensive campaign (“Benjamin McCulloch”, 2013; Cutrer, 2013). Flamboyant and ambitious, Van Dorn sought not only to crush Curtis, but also to retake Missouri and capture control of its vital resources, railroads, and waterways. In a letter to his wife he proclaimed, “I must have St. Louis” (Cox, 2012).

This period of engagement in Missouri, including the Battle of Wilson’s Creek specifically, and the run up to the coming Battle of Pea Ridge provide much of the backdrop in Steve Earle’s song ‘Ben McCulloch’. In the third verse, we learn:

Well they marched us to Missouri and we hardly stopped for rest

Then he made this speech and said “we’re comin’ to the test,

Well, we’ve got to take Saint Louie boys before the Yankees do,

If we control the Mississippi then the Federals are through (Earle, 1995).

Here, Earle reflects an accurate understanding of the strategic importance of Missouri, nearly echoing Van Dorn’s ‘must have St. Louis’ call. McCulloch may or may not have made such a speech to his collected troops, but clearly he would have concurred with the sentiment. As for marching with little rest, there can be no doubt that soldiers had a rough go under McCulloch’s command, as he himself reported it:

“I would here beg leave to call the attention of the department to the conduct of the men of my command during a rapid march of several days and nights, and some of the time with no other provision than beef and salt…” (Rose, 1958).

McCulloch somewhat sugar coats the reality in his report by neglecting to mention the weather, which Shea (2013) notes was “intensely cold” with “snow, sleet, and freezing rain.” Earle seems to recognize the same omission through the narrator in the second line of his fourth verse, “They forgot about the winter’s cold, and the cursed fever too” (Earle, 1995). The mention of fever is also an accurate portrayal of the conditions McCulloch’s men faced. Van Dorn himself is said to have began the campaign supine, coughing order from the back of a hospital wagon as he suffered from the flu (Owens, 2006). McCulloch too notes the toll illness took in providing a report of the pyrrhic victory at Wilson’s Creek:

“It has been asked why I did not pursue the enemy? In answering this question, I will merely state the facts and let my superiors say if it would have been advisable to advance under dire circumstances…Five hundred of these men had been too much enfeebled by sickness to be able to take the field” (Rose, 1958).

The remainder of Earle’s fourth verse relays the narrator’s experience of the loss of his brother at Wilson’s Creek, and the long retreat back into northwestern Arkansas in the face of Curtis’ advance. The song goes on to reference more of the inglorious truths about the war: grievous wounds from ever more destructive weapon technology, young men nearly still children losing their lives in battle, an honest questioning of the motivations of the conflict, and consideration of the slavery issue in a soldier’s decision to serve the Confederacy. The song’s final verse exposes the pervasiveness of desertion, with which both the Union and Confederacy had to contend, and alludes McCulloch’s final fate in the Battle of Pea Ridge.

Battle of Pea Ridge

With the fate of Missouri in the balance, 26,000 Union and Confederate soldiers clashed at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in what was the most decisive battle in the Trans-Mississippi theater (McPherson, 1988). Van Dorn had rushed to join the battered Southern forces that had withdrawn to the Boston Mountains on Curtis’ advance, creating two divisions from both McCulloch’s and Price’s forces. The convergence of these forces provided their best advantage: numbering roughly 16,000 men and 65 artillery pieces, Van Dorn’s Army of the West was, according to Shea (2013),

“the largest and best-equipped Confederate military force ever assembled west of the Mississippi River. No other Confederate army ever marched off to battle with a greater numerical superiority.”

Van Dorn’s first objective on the path to Missouri was to knock Curtis’ forces out of their way (and presumably the chip of the Union’s shoulder), and he deemed both surprise and speed essential to the success of this task (Cutrer, 2013; Shea, 2013). Recklessly overconfident, Van Dorn launched his counteroffensive on March 4, 1862, forcing a brutal three-day long forced march in harsh winter conditions, going so far as to order each soldier to carry only “his weapon, forty rounds of ammunition, a blanket, and three day’s rations” (Shea, 2013).

Choosing not to attack Curtis’ stout fortifications at Little Sugar Creek directly, Van Dorn hatched a plan to march all the way around to the Union rear, hoping to sever the Union lines of communication and supply. On March 4, 1862, Van Dorn ordered Price and McCulloch’s divisions to march north along the Bentonville Detour with the hopes of getting behind Curtis and cutting off his lines of communication. Owing to both his over-confidence and haste, Van Dorn allowed his supply trains to fall far behind his army, and wearied the men with a brutal three-day march in freezing conditions (Cox, 2012; Shea, 2013).

By sunrise on March 7, 1862, the lead forces of the cold, hungry, and exhausted Confederate column arrived at a position to the Union rear (Owens, 2006). From here, Van Dorn ordered McCulloch’s division at the rear of the Confederate column to take the lesser know Ford Road, while Price’s division was to proceed south along Telegraph Road, with both forces converging at Elkhorn Tavern (Cox, 2012; Hess, n.d.). Van Dorn hoped to produce a pincer maneuver with McCulloch and Price, while he attacked the Union’s rear by surprise (Owens, 2006).

Federal scouts, ‘Wild’ Bill Hickok among them, detected the attempt to flank long before sunrise, allowing Curtis time to reposition, keeping two-thirds of his army at Little Sugar Creek while ordering the remainder to intercept the Confederate forces (Bankes, 2006; Shea, 2013). Among these intercepting forces were twelve pieces of artillery, Colonel Nicholas Greusel’s brigade, and several cavalry units led by Colonel Cyrus Bussey-all assigned to a task force under the command of Colonel Peter Osterhaus, whose directive was to reconnoiter Ford Road (Shea, & Hess, 1992).

Firefight at Leetown – March 7th, 1862

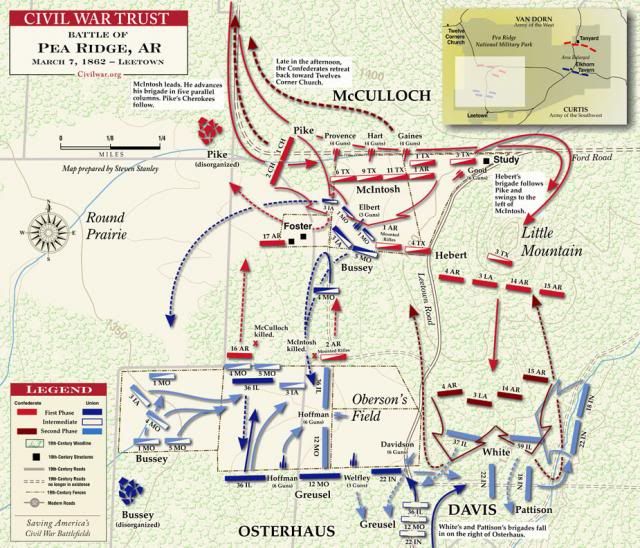

As McCullough’s division marched east on Ford Road they were spotted by Osterhaus who, despite being vastly outnumbered, ordered Bussey and his cannons to attack (Figure 2) (Shea 2013). Surprised, McCulloch counterattacked Bussey’s position with General James McIntosh’s 3,000-man strong cavalry brigade in a single massive charge (Shea, & Hess, 1992). Bussey’s comparatively tiny force was overrun, and a number of his cannons were captured. Meanwhile, Osterhaus had bought enough time to bring his infantry units into line along the south side of cornfield near Leetown (Shea, & Hess, 1992).

Figure 2. Leetown Fight; March 7, 1862. Reprinted from Civil War Trust website, Civilwar.org, Retrieved from http://www.civilwar.org/battle… Copyright 2013 by Civil War Trust.

Sensing victory through superior numbers, McCulloch made a command decision to delay the planned rally with Price at Elkhorn Tavern and instead wheel his entire division south toward Osterhaus’ weaker force (Cox, 2012; Shea, 2013). McCulloch’s decision would ultimately doom the Confederates at Pea Ridge, and played no small part in their eventual defeat in the war.

‘Ol Ben’, as the troops often called him, cut a somewhat curious figure for a Confederate commander: lanky, blue-eyed, and stern, he eschewed the Confederate uniform, preferring to fight in black velvet suits and polished Wellington riding boots. To assess the Union movements and position for himself, McCulloch (looking every bit a proper southern politician) rode forward through the thick underbrush and emerged into the open view of a handful of Union skirmishers from the 36th Illinois, who had been resting along a rail fence. McCulloch was shot from his horse, and was likely dead before he hit the ground.

When McIntosh realized McCulloch had fallen, he rashly led a small group in a desperate charge to recover the body, but met the same fate a mere 200 yards from where McCulloch lay (Shea, 2013). Confederate Colonel Louis Hébert, having no idea he was now the division’s ranking officer, led an attack that was halted by the arrival of Union Colonel Jefferson C. Davis (no relation to CSA President Davis), separating his forces and leading to his capture (Shea, & Hess, 1992). McCulloch’s division had lost the uppermost portion of its command structure in a span of hours.

Without leadership, the remnants of the division fell into chaos and confusion. A Confederate brigade of Native Americans under General Albert Pike attempted to drive off the ensuing Union attack, but lacking support was forced to withdraw (“The Battle of Pea Ridge”, 2013).

Elkhorn Tavern – March 7th and 8th, 1862

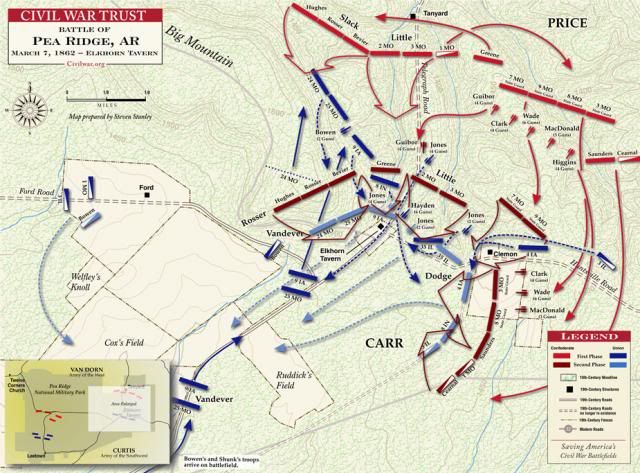

When Curtis had dispatched Osterhaus to the northwest to intercept McCulloch, he directed Colonel Eugene Carr to halt the advance of Price’s division, led by Van Dorn himself (Shea & Hess, 1992). On the morning of March 7, 1862, Carr arrived at Elkhorn Tavern about thirty minutes ahead of the Confederate march down Telegraph Road, took a defensive position and waited (“The Battle of Pea Ridge”, 2013). When Van Dorn’s column first struck the detached 24th Missouri, Carr’s infantry rushed to support the lone regiment, and though the Federal troops repeatedly resisted attack and regrouped, they were still vastly outnumbered (Figure 3) (Shea, & Hess, 1992).

Before long, Van Dorn and Price’s division had broken through Carr’s line of defense and taken up positions around Elkhorn Tavern (“The Battle of Pea Ridge”, 2013).

Figure 3. Elkhorn Tavern; March 7, 1862. Reprinted from Civil War Trust website, Civilwar.org, Retrieved from http://www.civilwar.org/battle… Copyright 2013 by Civil War Trust.

Fierce and nearly continuous attacks on the Union flanks forced Carr’s forces to retreat to safer ground at Ruddick’s Field (Figure 3). Even as more reinforcements dripped into Carr’s ranks, the Union forces continued to take a vicious pounding, with Carr himself thrice wounded. Carr refused to leave command, was later awarded the Medal of Honor for gallantry (Shea, & Hess, 1992). Though the Confederates had dislodged the Federals from their position, their failure to join with McCullough’s now defunct division ultimately denied Van Dorn a complete victory on the first day of fighting at Elkhorn Tavern (“The Battle of Pea Ridge”, 2013).

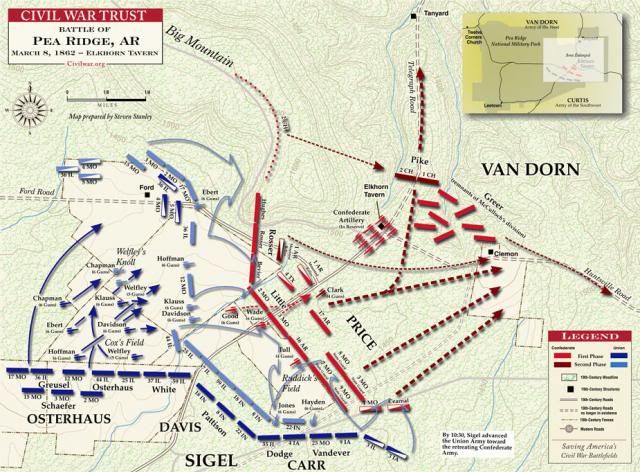

Despite their woeful condition after enduring such an imbalanced onslaught, Curtis used the cover of night to consolidate his forces, shoring his strength with the divisions of Osterhaus and Davis (Owens, 1996; Shea, & Hess, 1992) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Elkhorn Tavern; March 8, 1862. Reprinted from Civil War Trust website, Civilwar.org, Retrieved from http://www.civilwar.org/battle… Copyright 2013 by Civil War Trust.

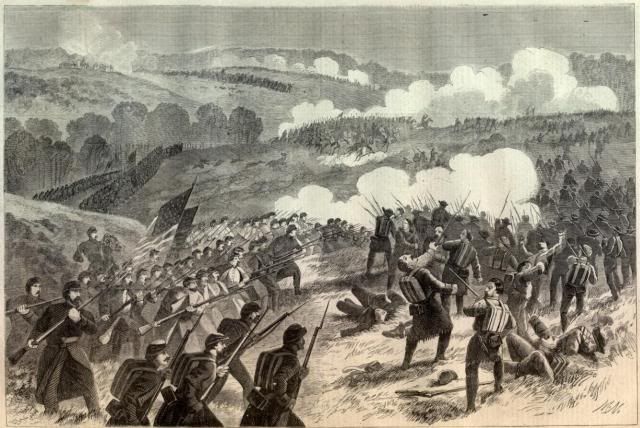

When the sun rose on the morning of March 8, 1862, it found the Confederate forces low on ammunition, out of food, and amassed in defensive positions (Owens, 2006). Sensing weakness Curtis began a furious artillery barrage upon on the Confederate line, and followed it with an assault on Van Dorn’s right flank led by General Franz Sigel (Beckenbaugh, 2009) (Figures 4 & 5). The division commanded by Davis launched a direct attack on the center after another intense shelling which pushing the thoroughly demoralized Confederates back, crumbling their defensive lines. Forced to withdraw, Van Dorn managed to lead a confused and chaotic escape. (“The Battle of Pea Ridge”, 2013).

Figure 5. “The Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas – The Final Advance of our Troops, March 8, 1862”. Originally published in Harper’s Weekly, March 29, 1862. Reprinted from Civil War Trust website, Sonofthesouth.net, Retrieved from http://www.sonofthesouth.net/l… Copyright 2013 by Civil War Trust.

Consequences of Defeat

The battle of Pea Ridge was among the deadliest confrontations that occurred in the Trans-Mississippi Theater. The Confederate forces suffered greatly, losing an estimated 4,600 casualties compared to the Union’s 1,349 (“The Battle of Pea Ridge”, 2013). The Union victory so demoralized Van Dorn that he limped his remaining forces all the way over to the east bank of the Mississippi River, leaving Arkansas utterly defenseless and allowing the Union to easily solidify its grip on Missouri-one which it never relinquished (Shea & Hess, 1992). With Missouri and St. Louis now secure, the Union focused its regional efforts on capturing the remainder of the Mississippi River Valley (Beckenbaugh, 2009).

Legacy

McCulloch’s sudden death is often cited as a primary cause in the Confederate defeat in the battle of Pea Ridge, and there’s little question that the loss had an impact on his contemporaries. Even before his death, McCulloch County was named after him in celebration of his heroic role in the Texas Revolution (Smyrl, n.d.). Mourned deeply after Pea Ridge-especially in the state of Texas-places like Fort McCulloch, and Camp Ben McCulloch were christened to his memory.

After the defeat at Pea Ridge Brigadier General Albert Pike felt that his Fort Davis headquarters were too open to Union attack, and so ordered the construction of a new fort in what is now Bryan County, Oklahoma. The eponymous Fort McCulloch’s strategic position was an improvement, and the post served as the main Confederate fortification in southern Indian Territory during the remainder of the Civil War (May, n.d.).

Organized in 1896 by about seventeen veterans of the war, Camp Ben McCulloch grew to become the largest United Confederate Veterans Camp in the South by 1930. Since its founding, the Camp has hosted an annual ‘reunion’ and has witnessed as many as six thousand visitors at a single event (“History of Camp Ben McCulloch”, 2013).

There are surely other remembrances, plaques, statues, or museum exhibits, especially in Texas where McCulloch’s fame is more enduring, but perhaps none have gained as much attention as Steve Earle’s song, whose album was Grammy™ nominated for Best Contemporary Folk Album.

Coda

Twenty-five years after the Battle of Pea Ridge, a monument was erected in honor of three Confederate commanders who fell, with the indomitable Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch among those immortalized (Johansson, 2011). These bleak words are inscribed in the stone:

O give me the land with a grave in each spot,

And names in the graves that shall not be forgot.

Yes, give me the land of the wreck and the tomb;

There’s a grandeur in graves, there’s a glory in doom (Johansson, 2011).

One can certainly admire the honor, skill, determination, and courage of a man like Ben McCulloch, but it presents something of a dilemma. Historian Howard Zinn has noted, “the chief problem in historical honesty isn’t outright lying. It is omission or de-emphasis of important data” (Holden, 2004). Ever the Southern partisan, McCulloch’s last will and testament, drawn up in 1858, calls specifically for the “purchase [of] a negro girl not to be less than twelve years of age, which negro girl I leave as a present to my niece,” and concludes “I leave my soul to God, who gave it, and my body to the State of Texas” (“Veteran Biographies”, 2012).

The causes that McCulloch served with such bravery and poise were often immoral, or entirely amoral. The wars he engaged in, and the atrocious violence by which they were prosecuted, were fueled in large part by racial enmity. That McCulloch was an ardent proponent of slavery, an unreconstructed Confederate patriot, and a traitor to the United States, are details Zinn would caution us not to neglect.

Ultimately, McCulloch employed his many admirable skills in defense of the abhorrent blight of human bondage-that ‘peculiar institution’ that has so scarred the consciousness of America. The heritage that men like McCulloch invoke is festooned with glory, but we are wise to remember the doom that accompanied it. Heritage is something to be cherished, but it should never be confused with history.

Goddamn you Ben McCulloch,

I hate you more than any other man alive.

And when you die you’ll be a foot soldier just like me,

In the devil’s infantry (Earle, 1995).

12 comments