Daily I listen to news reports discussing China owning a huge portion of our nations debt, and worrisome discussions about what that means about our economic future.

But today I want to discuss China’s impact on an alternate universe; the one inhabited by more than 11.5 million players world-wide. I am of course referring to the citizen players of World of Warcraft, known to those who play simply as WoW.

The Guardian UK has a recent piece by Rowena Davis Welcome to the new gold mines, discussing this practice.

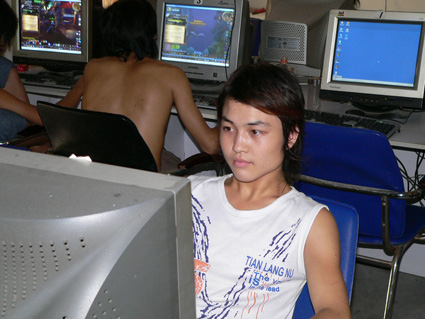

Li Hua makes a living playing computer games. Working from a cramped office in the heart of Changsha, China, he slays dragons and loots virtual gold in 10-hour shifts. Next to him, rows of other young workers do the same. “It is just like working in a factory, the only difference is that this is the virtual world,” says Li. “The working conditions are hard. We don’t get weekends off and I only have one day free a month. But compared to other jobs it is good. I have no other skills and I enjoy playing sometimes.”

Li is just one of more than 100 workers employed by Wow7gold, an internet-based company that makes more than £1m a year selling in-game advantages to World of Warcraft (WoW) players. Customers may ask for their avatar’s skill level to be increased (“power leveling”), or for a virtual magic sword or precious ore to be obtained. As one player put it: “Where there’s a demand, China will supply it.”

As a long time gamer, going back as far as Dungeons and Dragons, and then graduating to computer role-playing games like Ultima and Elder Scrolls, I am actually quite new to the multi-player phenomena.

I got WoW as a Christmas gift, and finally succumbed to a desire to see what the world of massively multiplayer online role-playing game’s, or MMORPG’s was all about.

I loved it, fun to play with others and chat while doing it, but much to my dismay, no sooner than I began to play I was inundated with “whispers” (private messages) from people I didn’t know, and wasn’t playing with which were usually things like “Hi Hon, need help?” or “hello Sir… how is your game progressing? (my character or “toon” is female) or “Want to chat?” quickly followed up by insistent queries about whether or not I want to “buy” gold with fast delivery.

Annoyed, but curious, I attempted to engage some of the intruders in a dialog, and also questioned some long term players in my game “Guild” about the practice.

Greedy Capitalism run amok seems to be the order of the day, much to the disgust of long time gamers who view buying gold rather than earning it in game play as cheating. But the anthropologist in me became even more curious, when I did a little research, made a few phone calls, and found that most of the people I conversed with were Asian; specifically Chinese.

I was even more abashed when I read reports of the working conditions of most of those people hired to “farm gold” for a daily living, but wasn’t particularly surprised. The virtual world is only mirroring the exploitation of cheap labor globally.

As far back as two years ago The NY Times covered this in a piece entitled:

The Life of the Chinese Gold Farmer at a time when subscribership was aroud 8 million

It was an hour before midnight, three hours into the night shift with nine more to go. At his workstation in a small, fluorescent-lighted office space in Nanjing, China, Li Qiwen sat shirtless and chain-smoking, gazing purposefully at the online computer game in front of him. The screen showed a lightly wooded mountain terrain, studded with castle ruins and grazing deer, in which warrior monks milled about. Li, or rather his staff-wielding wizard character, had been slaying the enemy monks since 8 p.m., mouse-clicking on one corpse after another, each time gathering a few dozen virtual coins – and maybe a magic weapon or two – into an increasingly laden backpack.

Twelve hours a night, seven nights a week, with only two or three nights off per month, this is what Li does – for a living

Here’s an old BBC clip covering the practice:

Blizzard, which is the owner and creator of WoW is attempting to ban the practice, but greed and status seeking trumps fair game play, and as fast as they try to limit exploiters, new methods are developed to circumvent their restrictions and penalties. Even the Chinese government has gotten in on the act, reports Davis:

Last year, the Chinese government acknowledged the rising significance of gold farming by introducing a 20% tax on the industry. But regulations on working hours, salaries, holidays and medical fees have not been extended with it. Yuan may be proud of her job, but she admits the long, unregulated hours are taking their toll. “The government should lay down the law. I would consider staying if conditions improved, but the game world is not a real career for me,” she says.With no regulatory oversight, the working conditions in gold farms vary massively. Yuan is one of the lucky ones. Anthony Gilmore, an independent filmmaker, has been investigating the industry as part of a documentary he is making, Play Money, which he hopes to release by the end of the year (playmoneyfilm.com). He has collected footage of firms in the middle of nowhere, where bunk beds sprawl alongside computers in the middle of freezing and dirty offices.

An online virtual world lesson in supply and demand economics, and an illustration of how what was simple a “game” is actually far more complex.

Davis interviewed a gold-buyer as well.

Thousands of miles away, western consumers are driving these industries, pumping hard-earned cash into products and services that exist only in fantasy lands. I ask Jamie el-Banna, a 24-year-old gamer from the UK, what makes him spend his money on these sites. “The reason people buy gold is the same reason they pay people to wash their car – they would rather spend money than do it themselves” he says. “You could spend time farming gold, say, 20 real-life hours. Or you could go to work for two hours and earn the money to buy the gold. If I’m playing I want to play, not do boring tasks. Go back some years, and a job involving a computer was a skilled job. Nowadays, keyboards and mice are the new ploughs and shears.”But does he ever consider the conditions of the workers supplying these services?

“I don’t think about the workers. I think about the product. I’m sure the wage that gold farmers are paid is low. Manual labourers in third-world countries probably earn a similar amount, but I doubt you would ask someone this kind of question if you saw them drinking a cup of coffee.”

She concludes with some economic data:

At present, the vast majority of gold farming takes place in developing countries, with four-fifths of production estimated to take place in China. The jury is still out on whether this industry is spawning a new generation of “virtual sweatshops” or whether it is a massive opportunity for countries seeking to develop through the hi-tech economy.

So should I buy Wow gold now, as I level my herb-picking mage, with dreams of a flying

mount to enhance my game play?, I muse.

I won’t, but the thought did fleetingly drift into my head. Guess I’m old-school, and my solution to the problem of the WoW economy has been to create a commune – multiple characters to craft and mine resources and share them with each other and friends.

Time for my morning coffee, and then a trip into the workaday world of WoW, where I will struggle to fend off the forces of evil, and greed.

7 comments