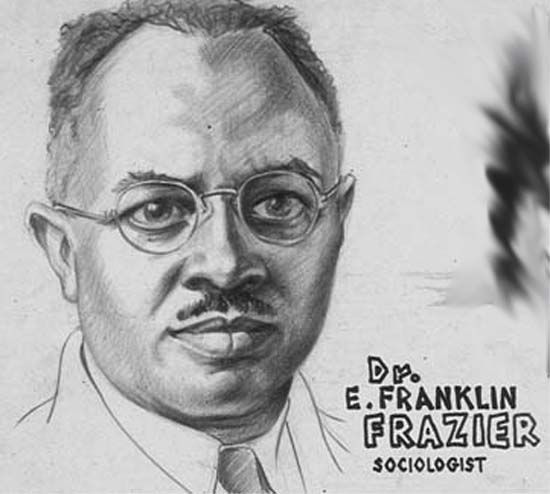

At a time of heightened awareness and discussion of race, racism and racial prejudice in certain sectors of our populace, even in the face of efforts to dismiss them with claims that as of the election of Barack Obama we are currently “post-racial”, I would like to highlight the contributions of Edward Franklin Frazier to what we know and understand about oppressed communities in general and the black community in specific.

September 24th is the birthday of one of this nation’s foremost sociologists, who was born in Baltimore, MD in 1894 and who died May 17, 1962, in Washington DC where he was Professor Emeritus at Howard University. At the time of his death he was still carrying a full teaching load.

Frazier was a founding member of the D.C. Sociological Society, serving as President of DCSS in 1943-44. Frazier also served as President of the Eastern Sociological Society in 1944-45. In 1948, Frazier was the first black to serve as President of the American Sociological Society (later renamed Association). His Presidential Address “Race Contacts and the Social Structure,” was presented at the organization’s annual meeting in Chicago in December 1948.

It wasn’t until I was in graduate school that I became familiar with his extensive body of work. I was researching social stratification in the black community and my advisor, anthropologist Delmos Jones, suggested that I should dive into Frazier’s work. Del remarked “he’s fallen out of fashion” but contributed more to the documentation and academic study of blacks in the U.S. than any other scholar.

Recently, watching the frenzies of racism that have erupted across the nation and online, from right wing sectors, I have thought of the racist response to Obama’s election as almost pathological and went back to take a look at Frazier’s most controversial paper, “The pathology of race prejudice“, published in 1927.

Rarely do papers in academic journals evoke a firestorm of protest, but this one did.

Anthony Platt wrote about this in his article “The Rebellious Teaching Career of E. Franklin Frazier” in The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education.

Of all Frazier’s writings in the 1920s, “The Pathology of Race Prejudice” was the most controversial and evoked the most discussion and debate. Using the familiar categories of Freudian psychology, Frazier argued that racism was a form of “abnormal behavior,” characterized by dissociation, delusional thinking, rationalization, projection, and paranoia. White people in the South, he argued, were literally driven mad by the “Negro-complex,” which made “otherwise kind and law-abiding [people] indulge in the most revolting forms of cruelty towards black people.” Frazier completed the article in 1924 but, not surprisingly, could not get it published for almost three years. “The Pathology of Race Prejudice” appeared in the June 1927 issue of Forum, a liberal periodical that addressed social policy issues. By this time Frazier had intended to leave Atlanta at the end of the summer to resume his doctoral studies at the University of Chicago. But he was forced to leave town in a hurry in June when somebody sent a copy of his article to the Atlanta press.

Within a week of his article’s appearing in Forum, Atlanta’s Constitution carried an editorial condemning “this psychopathologician” as “more insane by reason of his anti- white complex than any southerner obsessed by his anti-negro repulsions.” As a result of the publicity in the Atlanta press, the Fraziers were threatened with lynching and friends urged them to leave town as quickly as possible. Their departure from Atlanta in June 1927 quickly assumed legendary status with Frazier portrayed as a “combative hero, fighting a rear-guard action against the Ku Klux Klan.”

Frazier was neither insane, nor anti-white. He was however, an astute observer of both the black community and the greater white society that contained, restrained and oppressed it. He was “race conscious“, and given his birth and family status could hardly escape the racist constraints surrounding him.

Frazier, whose paternal grandfather was a slave, was born in 1894 and raised in the 1800 block of Druid Hill Ave. He was 10 years old when his father, a bank messenger, died, and to help support his mother, two brothers and two sisters, Frazier sold newspapers before school and in the afternoon delivered groceries.

After graduating from the old Colored High School in 1912, he earned his bachelor’s degree from Howard University in 1916, where he had fallen under the spell of W.E.B. Du Bois, sociologist, civil rights activist and author. At Howard, he joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, developed an interest in socialism and protested U.S. entry into World War I.

Until attending Clark University in Worcester, Mass., where he earned a master’s degree, Frazier had never attended school with white students. He earned a doctorate from the University of Chicago in 1931.”Even though he was born into a segregated world, he claimed every time he walked to school he spat on the walls of Johns Hopkins University (then at Eutaw Street and Druid Hill Avenue) because he knew he couldn’t go there. His race-consciousness was aroused at an early age,” said Anthony M. Platt, a professor emeritus in social work at California State University at Sacramento and author of E. Franklin Frazier Reconsidered, published by Rutgers University Press in 1991.

His scholarship focused on blacks.

His 1932 Ph.D. dissertation The Negro Family in Chicago, later released as a book The Negro Family in the United States in 1939, analyzed the historical force that influenced the development of the African-American family from the time of slavery. The book was awarded the 1940 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for the most significant work in the field of race relations. This book was among the first sociological works on blacks researched and written by a black person. He helped draft the UNESCO statement The Race Question in 1950.

Going back and re-reading his paper gave me pause.

He gave an illustration:

Some years ago a mulatto went to a small Southern town to establish a school for Negroes. In order not to become persona non grata in the community, he approached the leading white residents for their approval of the enterprise. Upon his visit to one white woman he was invited into her parlor and treated with the usual courtesies shown visitors; but when this woman discovered later that he was colored, she chopped up the chair in which he had sat and, after pouring gasoline over the pieces, made a bonfire of them.

and then wrote:

From a practical viewpoint, insanity means social incapacity. Southern white people afflicted with the Negro-complex show themselves incapable of performing certain social functions.They are, for instance, incapable of rendering just decisions when

white and colored people are involved

and concluded:

Yet, – from the point of view of Negroes, who are murdered if they believe in social equality or are maimed for asking for an ice cream soda, and of white people, who are threatened with similar violence for not subscribing to the Southerner’s delusions,-such behavior is distinctively antisocial. The inmates of a madhouse are not judged insane by themselves, but by those outside. The fact that abnormal behavior towards Negroes is characteristicof a whole group may be an example illustrating Nietzsche’s observation that “insanity in individuals is something rare,-but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs it is the rule.”

I think of Trayvon Martin murdered after buying Skittles and the incapacity of rendering a just decision in so many current cases of racial murder.

The current meme of young black men’s “thuggishness” as an excuse for murder, or incarceration and disenfranchisement is summed up in one of Frazier’s pithy quotes:

“The closer a Negro got to the ballot box, the more he looked like a rapist.”

Granted, Frazier’s paper focused on the South – simply because he was living in a southland of lynching and racial terrorism, but his other works look at poverty, segregation, economic inequality in the urban north, and includes a probing and critical look at the black middle class, in Black Bourgeoisie

It is important that we don’t forget the work of black scholars who have laid a foundation for modern discourse and study of race and racial injustices.

They haven’t forgotten him at Howard University, which has named one of its programs in his honor: E. Franklin Frazier Center for Social Work Research

18 comments