Some of the discussion about universal standards of morality in the Haiti thread and Cheryl’s diary got my mind wandering down a familiar but, of late, not oft visited path. It occurs to me that it has largely fallen out of my consciousness because I have no one with whom to discuss such ideas. Maybe moose can provide me with some insight.

Some of the discussion about universal standards of morality in the Haiti thread and Cheryl’s diary got my mind wandering down a familiar but, of late, not oft visited path. It occurs to me that it has largely fallen out of my consciousness because I have no one with whom to discuss such ideas. Maybe moose can provide me with some insight.

As a child, before I knew terms like cultural relativism and anti-realism, I was already of the opinion that morality was largely subjective and certainly not absolute. I don’t know that I ever thought there were universal standards of right and wrong. It seemed apparent to me at an early age that everyone’s “morality” differed, even if only in subtle ways, and as I learned about history and other cultures, I only became increasingly entrenched in that viewpoint. I still believe that people are neither inherently good nor bad — that possibly, in fact, our natural condition is largely amoral — and that what we call morality stems primarily from two sources: Fear and societal norms. Actually, that can be simplified even further. I could just as easily say that morality is spawned from fear alone, since I believe fear to be the impetus behind the establishment of many social norms and cultural standards of morality.

But whatever the source, the fact is that most of us do internalize moral standards from somewhere. We do have a sense of what we consider just and unjust, right and wrong, moral and immoral, good and evil. It should be noted, perhaps, that I do not consider this view of humanity to be particularly cynical. Though we are capable of great harm, we are also capable of tremendous good. Few of us are paragons of virtue, and though I do not believe we come into the world with an inborn sense of morality or justice, for the most part, an understanding of those concepts — individualized as they may be — does develop.

Please feel free to disagree with any and all of this in the comments. I am less adamant about some of these views than I am about my religious (anti-religious) opinions, and thus will be more inclined to be persuaded to see other viewpoints.

But perhaps to start a whole new discussion here. One thing I’ve wanted to discuss for a very long time is in a similar vein, in that it’s a bit morally relativistic. The opinion one might have about the issue here has much to do with what one’s conception of “evil” is, if one has concept of it at all. It’s a difficult issue with which most people in the field of psychology don’t seem to bother. For me, one example stands out in particular. Much of the research on the phenomenon known as psychopathy is conflicting and/or ambiguous. It’s certainly varying, and people have different interpretations of what the term “psychopath” really means. The concept of psychopathy has morphed and evolved over the years. Philippe Pinel, born in the mid 1700s, perhaps articulated the first modern day notion of psychopathy, coining the phrase manie sans delire, or “insanity without delirium.” Psychopaths have been described as “moral lunatics,” reflecting their tendency to be capable of functioning and interacting in an ofttimes seemingly logical manner, but possessing a perceived moral deficiency which prevents them from conforming to traditional social mores.

Today, many psychologists believe that the psychopath is what we now label Antisocial Personality Disorder, the DSM-IV-TR criteria for which are as follows:

A. There is a pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others occurring since age 15 years, as indicated by three (or more) of the following:

- Failure to conform to social norms with respect to lawful behaviors as indicated by repeatedly performing acts that are grounds for arrest

- Deceitfulness, as indicated by repeated lying, use of aliases, or conning others for personal profit or pleasure

- Impulsivity or failure to plan ahead

- Irritability and aggressiveness, as indicated by repeated physical fights or assaults

- Reckless disregard for safety of self or others

- Consistent irresponsibility, as indicated by repeated failure to sustain consistent work behavior or honor financial obligations

- Lack of remorse, as indicated by being indifferent to or rationalizing having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from another.

B. The individual is at least age 18 years.

C. There is evidence of conduct disorder with onset before age 15 years.

D. The occurrence of antisocial behavior is not exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or a manic episode.

On the other hand, there are some — myself included — who would disagree with the view that someone labeled APD is a psychopath in the “traditional” sense. It has been posited that there are three types: The neurotic psychopath, the dyssocial psychopath, and the primary (true) psychopath. Neurotic and dyssocial psychopaths are not “evil” in the way that most people think of it — they are as they are due to emotional instability or their environment. The primary psychopath, however, is by public perception “true evil” without adequate cause. Most people think psychopath and think Dahmer, Gacy, or (for more of a pop culture reference) Hannibal Lecter. But someone could fit the APD criteria and just be a right asshole, not a murdering psychopath. And in fact, technically, psychopaths in general terms do not have to be murderers or even criminals, as you will glean from the lists below. Politicians and priests, for example, can easily fit the profile(s). Two of the most widely used checklists for psychopathy are Hare’s and Cleckley’s. They are psycho-diagnostic tools, but perhaps no longer in the “official” sense, since “psychopath” is not a diagnosis in the current incarnation of the DSM.

Hare’s Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R)

Factor1: Personality “Aggressive narcissism”* Glibness/superficial charm

* Grandiose sense of self-worth

* Pathological lying

* Conning/manipulative

* Lack of remorse or guilt

* Shallow affect

* Callous/lack of empathy

* Failure to accept responsibility for own actionsFactor2: Case history “Socially deviant lifestyle”

* Need for stimulation/proneness to boredom

* Parasitic lifestyle

* Poor behavioral control

* Promiscuous sexual behavior

* Lack of realistic, long-term goals

* Impulsivity

* Irresponsibility

* Juvenile delinquency

* Early behavior problems

* Revocation of conditional releaseTraits not correlated with either factor

* Many short-term marital relationships

* Criminal versatility

Cleckley’s Psychopathy List, a bit more dated — published in 1955 in his book Mask of Insanity

- Superficial charm and intelligence

- No delusions

- No psychoneurotic behavior

- Unreliable

- Pathological lying

- No remorse

- Insufficient motivated antisocial behavior

- Poor judgment and doesn’t learn from experience

- Cannot love

- Poor in primary experience in feelings and emotions

- Loss of insight

- Not responsive in over all interpersonal reactions

- Obnoxious behavior when drunk and, at times, when sober

- Suicide threats rarely attempted

- Sex lives impersonal

- Fails to follow a plan of life

Regardless of which checklist or criteria one thinks best diagnoses psychopathy, there are some fundamental biological differences between “us” and “them.” Perhaps the most telling is their higher threshold for certain types of stimuli, including fear and other forms of excitement. This trait has some interesting effects, the most measurable of which is the psychopath’s response to polygraph machines. When their galvanic skin responses are tested, it has been found that they show decreased levels of emotional arousal. This lower ectodermal response makes it easier for them to lie without detection. Psychopaths are sometimes described as “thrill seekers,” and this is thought to be due, in part, to that higher threshold for stimuli. As a result, they may engage in dangerous activities or risky behaviors to compensate when seeking the excitement we might get from watching a horror movie or arguing with someone on a blog. What excites us might not excite them. On a related note, they also seem to have no internal moral compass — perhaps because they have little fear — and in true psychopaths, that characteristic appears to be inborn, rather than something learned from their environments.

Regardless of which checklist or criteria one thinks best diagnoses psychopathy, there are some fundamental biological differences between “us” and “them.” Perhaps the most telling is their higher threshold for certain types of stimuli, including fear and other forms of excitement. This trait has some interesting effects, the most measurable of which is the psychopath’s response to polygraph machines. When their galvanic skin responses are tested, it has been found that they show decreased levels of emotional arousal. This lower ectodermal response makes it easier for them to lie without detection. Psychopaths are sometimes described as “thrill seekers,” and this is thought to be due, in part, to that higher threshold for stimuli. As a result, they may engage in dangerous activities or risky behaviors to compensate when seeking the excitement we might get from watching a horror movie or arguing with someone on a blog. What excites us might not excite them. On a related note, they also seem to have no internal moral compass — perhaps because they have little fear — and in true psychopaths, that characteristic appears to be inborn, rather than something learned from their environments.

The interesting thing about the lack of a moral compass is, if they have no sense of morality, can they be by any definition “evil,” despite what atrocities they might commit? I don’t believe that any human being is pure evil — that sort of condemnation is too absolute. What I am wondering, however, is how morally culpable someone with no internalized sense of morality can truly be.

I regularly speed, despite knowing that it is against the law and could get me into trouble. My desire to get where I’m going more quickly often outweighs my fear of consequences (e.g., tickets, accidents, etc.) I do not see speeding, as a rule, as “morally wrong,” despite knowing that technically it could cause harm to others. Does that make me a bad person? Evil? I am both breaking a codified rule and committing an act which I am aware could harm other human beings, for selfish purposes.

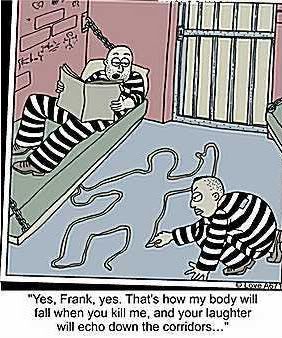

If we can say “no” to the above, then can we also not say that an individual lacking a moral compass because that is the way they were born is also not a “bad person,” not “evil” — no matter what crimes they may commit? The psychopath may fail to internalize societal norms. S/he is devoid of the fear which prevents many from committing the crimes they might otherwise — fear of being caught, fear of other social stigmas and repercussions. S/he has no concern for the safety of others because s/he was not wired to care. To him/her, murder may be no worse than speeding — s/he acknowledges that the consequences are greater, but from an internal perspective, perhaps it seems no worse, no more “wrong.” So is that person, at such a point, even capable of “evil”? Capable of great harm, yes, and even intent — but “evil”?

My contention is that the primary psychopath is, in effect, amoral — possibly, in fact, the only perfectly amoral human being. S/he is essentially untainted by society’s views of morality, typically instilled by fear, habit and necessity, and thus exists throughout his/her lifespan in a purely amoral state. This “moral imbecile” goes through life with the moral and ethical make-up of an untrained infant. Given that, despite whatever crimes s/he might commit, s/he is fundamentally/biologically/genetically formed in such a way that it is impossible to be “evil.” While the world is not so black and white that we can say anyone is fully evil, should we have different standards of judgment for a person who is incapable of understanding or relating to society’s conventions of morality?

And in making that supposition, what am I implying for the rest of humanity? That they have a greater obligation to do good (or at least not to do harm) because they are more capable? Simply because they feel more and more readily conform to social mores? Are we more culpable for our actions and behaviors based on our capabilities? In that case, which wins out — our capabilities as provided by our genes or by our environment? And if those of us who are capable of more are indeed responsible for more, is that fair, right, or just?

I don’t really know the answers to some of these questions.

Thoughts?

Note: I have not sourced this diary, as much of my information comes from old books which have not yet been moved to this apartment, or were found through databases to which I cannot readily link. If anyone has a serious question regarding the accuracy or veracity of any of the above, let me know, and I will hunt down a source that can be verified and cited.

62 comments