Check out Danielle Nierenberg’s Op-Ed, based on research for the Worldwatch Institute’s Nourishing the Planet project, featured on the front page of the Zambia Daily Mail. Cross posted from Border Jumpers, Danielle Nierenberg and Bernard Pollack.

In the United States, it seems like we only hear about what’s going wrong in Africa. We see and read stories about famine, HIV/AIDS, disease, or conflict.

In the United States, it seems like we only hear about what’s going wrong in Africa. We see and read stories about famine, HIV/AIDS, disease, or conflict.

In fact, few Americans will ever step foot in countries like Malawi or Zambia, largely because our media often scares people away.

As I travel across Africa, working as a senior researcher for the Worldwatch Institute as co-project director of Nourishing the Planet, I am hoping to show a different side of the continent.

Instead of stories of despair, we are looking at and sharing stories of success and hope, highlighting African-led innovations that are helping to alleviate hunger and poverty in an environmentally sustainable way.

After spending time in Lusaka meeting with non-governmental organisations, non-profits and projects on the ground, I discovered that this country is filled with incredible individuals and organisations – making my job very easy, and in many ways serving as a model for the rest of the continent.

Here are some examples:

COMACO, an organisation founded over 30 years ago to conserve local wildlife, helps farmers improve their agricultural practices in ways that can protect the environment – such as through conservation farming – while also creating a reliable market for farm products.

It organises the farmers into producer groups, encouraging them to diversify their skills by raising livestock and bees, growing organic rice, using improved irrigation and fisheries management and other practices so that they don’t have to resort to poaching elephants or other wildlife.

The United Nations World Food Programme’s Purchase for Progress (P4P) programme, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, and the Belgian government, is working with the private sector, governments and NGOs to provide an incentive for farmers to improve their crop management skills and produce high-quality food, create a market for surplus crops from small and low-income farmers and promote local processing and packaging of products.

Mobile Transactions, a financial services company for the ‘unbanked’ in Zambia, allows customers to use their phones like an ATM card. Over the last decade, cell-phone use in Africa has increased fivefold and farmers are using their phones to gain information about everything from markets to weather.

By using Mobile Transactions, farmers are not only able to make purchases and receive payment electronically; they are also building a credit history which can make getting loans easier.

And Mobile Transactions also works with USAID’s PROFIT programme to help agribusiness agents make orders for inputs, manage stock flows and communicate more easily with agribusiness companies and farmers.

Perhaps most importantly, the partnership helps agents better understand the farmers they are working with so that they can provide the tools, inputs and education each farmer and community needs.

Care International’s work in Zambia has two main goals: increase the production of staple crops and improve farmers’ access to agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilisers. But instead of giving away bags of seed and fertilisers to farmers, Care is “creating input access through a business approach”, not a subsidy approach, according to Steve Power, assistant country director for Zambia.

One way they’re doing this is by creating a network of agro-dealers who can sell inputs to their neighbours as well as educate them about how to use hybrid seeds, fertilisers and other inputs. At the same time, “we are mindful” of the benefits of local varieties of seeds.

Jan Nijhoff of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and Michigan State University, who is also an advisor on Worldwatch’s Nourishing the Planet project, says COMESA’s mission is to promote regional economic integration through increased co-operation and integration of trade, customs, transport, communication, technology, energy, and gender, as well as agriculture, environment and natural resources.

Throughout most of my meetings, a theme I hadn’t heard as much in other African countries continued to surface – linking farmers to markets.

While at times I was sceptical about this focus on the private sector, the more I talked to farmers, NGOs, development workers and policy-makers, the more convinced I became that farmers need not just inputs to grow their crops, but a profitable – and sustainable – market to sell those crops.

In developing this model, it’s clear that Zambia is leading the way and creating examples that could work and be scaled up in other countries across the continent. – www.nourishingtheplanet.org

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy our diary every day we invite you to get involved:

1. Comment on our daily posts — we check for comments everyday and want to have a regular ongoing discussion with you.

2. Receive regular updates–Join the weekly BorderJumpers newsletter by clicking here.

3. Help keep our research going–If you know of any great projects or contacts in West Africa please connect us connect us by emailing, commenting or sending us a message on facebook.

We’ve taken some long bus rides in Africa. We spent eight bumpy hours on a bus from Nairobi to Arusha and another eight from Arusha to Dar Es Salaam.

We’ve taken some long bus rides in Africa. We spent eight bumpy hours on a bus from Nairobi to Arusha and another eight from Arusha to Dar Es Salaam. In Rwanda, more than 85 percent of the population’s livelihood depends on small-scale agriculture. And the majority of primary school students-roughly 60 percent- will return to rural areas to make their living in ways, instead of going on to secondary or vocational schooling or university.

In Rwanda, more than 85 percent of the population’s livelihood depends on small-scale agriculture. And the majority of primary school students-roughly 60 percent- will return to rural areas to make their living in ways, instead of going on to secondary or vocational schooling or university. The

The  In the United States, it seems like we only hear about what’s going wrong in Africa. We see and read stories about famine, HIV/AIDS, disease, or conflict.

In the United States, it seems like we only hear about what’s going wrong in Africa. We see and read stories about famine, HIV/AIDS, disease, or conflict. Gertrude Hambira doesn’t look like someone who gets arrested regularly. Nor do the other women and men in suits who work with her at the General Agricultural and Plantation Workers Union of Zimbabwe (GAPWUZ), formed in the mid-1980s to protect farm laborers. But arrest, harassment and even torture have been regular occupational hazards for Gertrude-the General Secretary of GAPWUZ-and her staff for many years.

Gertrude Hambira doesn’t look like someone who gets arrested regularly. Nor do the other women and men in suits who work with her at the General Agricultural and Plantation Workers Union of Zimbabwe (GAPWUZ), formed in the mid-1980s to protect farm laborers. But arrest, harassment and even torture have been regular occupational hazards for Gertrude-the General Secretary of GAPWUZ-and her staff for many years. Name: Hans Herren

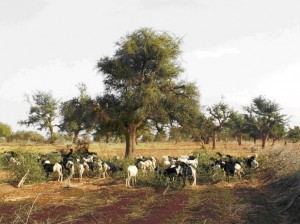

Name: Hans Herren For centuries, farmers in the Sahel-a band of land that crosses Africa at the southern fringe of the Sahara Desert-used rotational tree farming to provide year-round harvests and a consistent source of food, fuel, and fertilizer. But severe droughts and rapid population growth in the 1970s and 80s significantly degraded the Sahel’s farmland, leading to the loss of many indigenous tree species and leaving the soil barren and eroded. With the loss of the trees went the knowledge, traditions, and practices that had kept the region fertile for hundreds of years.

For centuries, farmers in the Sahel-a band of land that crosses Africa at the southern fringe of the Sahara Desert-used rotational tree farming to provide year-round harvests and a consistent source of food, fuel, and fertilizer. But severe droughts and rapid population growth in the 1970s and 80s significantly degraded the Sahel’s farmland, leading to the loss of many indigenous tree species and leaving the soil barren and eroded. With the loss of the trees went the knowledge, traditions, and practices that had kept the region fertile for hundreds of years. As Iceland’s erupting volcano strands thousands of air travelers across Europe and worldwide, a less publicized but arguably more costly catastrophe is mounting 15,000 miles away: piles of

As Iceland’s erupting volcano strands thousands of air travelers across Europe and worldwide, a less publicized but arguably more costly catastrophe is mounting 15,000 miles away: piles of  I grew up in Westmount as an only child with a relatively privileged middle-class life. I attended Selwyn House elementary, and we had season tickets to the Canadiens at the old Forum.

I grew up in Westmount as an only child with a relatively privileged middle-class life. I attended Selwyn House elementary, and we had season tickets to the Canadiens at the old Forum. Wildlife conservation and sustainable farming practices are becoming increasing prevalent across sub-Saharan Africa (see

Wildlife conservation and sustainable farming practices are becoming increasing prevalent across sub-Saharan Africa (see