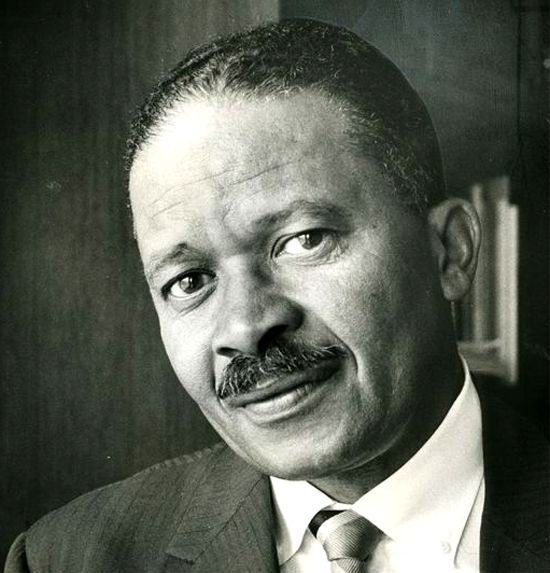

One of the most interesting positive events on the racial history front to garner some national press attention last week was the highlighting of the life and career of Harry S. McAlpin.

The African American Registry (of course) had the event marked as part of our history, but I’m elated to see that this history has been exposed to a much wider audience.

Date:

Tue, 1944-02-08On this date in 1944, Harry S. McAlpin was the first African American journalist admitted to a white house press conference.

He was working for the National Negro Press Association and the Atlanta Daily World. On that day, McAlpin was waiting to go into the Oval Office, where they had press conferences at that time, when a white reporter from the New Orleans Times-Picayune spoke to him. The reporter who was head of the White House Press Correspondents Association said, “Harry, we’re not happy that you’re here, but we can’t stop you from going to these press conferences. However, if you don’t go to these press conferences, we will come out afterward and we will tell you everything that happened. You will have the exact same notes we do. You will find it possible to write the same stories that we do. And, if you don’t go, we will let you join the White House Press Correspondents Association.”

McAlpin went into the press conference and at the end of it he made a point of going by President Franklin Roosevelt’s desk. Roosevelt shook McAlpin’s hand and said, “Harry, I’m glad to have you here.” In 1947, the Negro Newspaper Publishers association and some individual news correspondents were accredited to the Congressional Press Galleries and the State Department. The early journalists accredited were James L. Hicks, Percival L. Prattis and Louis Lautier.

There was a flurry of stories like this one below, and others from

AP , thanks to the coverage of President Obama’s remarks, but I think it is important that we not only remember McAlpin, but look at how far we have come since the 40’s and how far we need to go.

Tue, 1944-02-08On this date in 1944, Harry S. McAlpin was the first African American journalist admitted to a white house press conference.

He was working for the National Negro Press Association and the Atlanta Daily World. On that day, McAlpin was waiting to go into the Oval Office, where they had press conferences at that time, when a white reporter from the New Orleans Times-Picayune spoke to him. The reporter who was head of the White House Press Correspondents Association said, “Harry, we’re not happy that you’re here, but we can’t stop you from going to these press conferences. However, if you don’t go to these press conferences, we will come out afterward and we will tell you everything that happened. You will have the exact same notes we do. You will find it possible to write the same stories that we do. And, if you don’t go, we will let you join the White House Press Correspondents Association.”

McAlpin went into the press conference and at the end of it he made a point of going by President Franklin Roosevelt’s desk. Roosevelt shook McAlpin’s hand and said, “Harry, I’m glad to have you here.” In 1947, the Negro Newspaper Publishers association and some individual news correspondents were accredited to the Congressional Press Galleries and the State Department. The early journalists accredited were James L. Hicks, Percival L. Prattis and Louis Lautier.

There was a flurry of stories like this one below, and others from AP , thanks to the coverage of President Obama’s remarks, but I think it is important that we not only remember McAlpin, but look at how far we have come since the 40’s and how far we need to go.

White House reporters to right WWII-era racism

Seventy years ago, Harry S. McAlpin, a reporter for The Atlanta Daily World and other African American newspapers – and a future president of the Louisville NAACP – became the first black reporter to cover a presidential news conference at the White House. President Franklin D. Roosevelt invited McAlpin into one of his twice-a-week gatherings with the all-white White House press corps after repeated requests from African-American publishers, who had complained about being denied access.

Thomma told me the White House Correspondents’ Association had blocked black reporters from FDR’s news conferences. And the group’s members resented McAlpin’s presence in their midst. McAlpin told The Courier-Journal in 1964 that one of the correspondents urged him not to go into the Feb. 8, 1944, briefing, that he might step on the foot of a white reporter “and there might be a race riot.” “I told him that if there was going to be a race riot in a group like that over a little thing like that – why it would be the greatest Negro news story of the year and I wouldn’t want to miss it,” McAlpin said. “He went in and made history,” Thomma said. “But he never was admitted to the White House Correspondents Association.”

McAlpin left the White House beat in 1945 and covered the final months of World War II. Originally from St. Louis, he moved to Louisville in 1949, practiced law, became a civil-rights activist and ultimately head of the Louisville chapter of the NAACP. He died in 1985. Now the White House Correspondents’ Association is naming a journalism scholarship after him. The first recipient was scheduled to be introduced at the Saturday dinner and meet President Barack Obama. McAlpin’s son, Sherman, of Bowie, Md., his wife and daughter were invited as guests, too. “As we mark our centennial, we were determined to remember both the good and the bad of those 100 years. Our treatment of Harry McAlpin was part of the bad,” Condon told me. “But today, 70 years later, we hope this brings some attention to the remarkable work that he did.”

President Obama’s remarks at the dinner about McAlpin:

On a more serious note, tonight reminds us that we really are lucky to live in a country where reporters get to give a head of state a hard time on a daily basis — and then, once a year, give him or her the chance, at least, to try to return the favor.

But we also know that not every journalist, or photographer, or crewmember is so fortunate, because even as we celebrate the free press tonight, our thoughts are with those in places around the globe like Ukraine, and Afghanistan, and Syria, and Egypt, who risk everything — in some cases, even give their lives — to report the news.

And what tonight also reminds us is that the fight for full and fair access goes beyond the chance to ask a question. As Steve mentioned, decades ago, an African American who wanted to cover his or her President might be barred from journalism school, burdened by Jim Crow, and, once in Washington, banned from press conferences. But after years of effort, black editors and publishers began meeting with FDR’s press secretary, Steve Early. And then they met with the President himself, who declared that a black reporter would get a credential. And even when Harry McAlpin made history as the first African American to attend a presidential news conference, he wasn’t always welcomed by the other reporters. But he was welcomed by the President, who told him, I’m glad to see you, McAlpin, and I’m very happy to have you here.

Now, that sentiment might have worn off once Harry asked him a question or two — (laughter) — and Harry’s battles continued. But he made history. And we’re proud of Sherman and his family for being here tonight, and the White House Correspondents Association for creating a scholarship in Harry’s name. (Applause.)

McAlpin’s story is part of the history of the black press in the U.S. Few people know the name of men like John H. Sengstacke.

b. 1912 He was the visionary publisher of The Chicago Daily Defender, an influential newspaper in black communities nationwide. Sengstacke bedeviled Roosevelt and Truman and had access to the White House until his death. But he avoided publicity, preferring to let the clout of his paper do the talking.

Integration was a blessing and curse. It broadened opportunity and dismantled American apartheid. But it swept away some of the most substantial institutions that African-Americans had ever controlled. Negro colleges faltered and some collapsed when white schools integrated and skimmed off the black middle class. Inner-city churches, civic groups and neighborhoods came unraveled as affluent Negroes fled through newly opened doors to the suburbs. No institution worked harder for desegregation — or suffered more gravely when it arrived — than the 300 or so newspapers that made up the Negro press. Throughout the first half of the century, legendary papers like The Chicago Defender, The Pittsburgh Courier and The Baltimore Afro-American had campaigned against discrimination in housing, in the military and in public accommodations. But with the civil rights movement finally under way — and white papers belatedly interested in Negro news — black readers slipped steadily away, leaving the Negro press to wither.

Only in the last 10 years have historians begun to explore this period. But with the barest outlines of the story in place, the Charles Foster Kane of the Negro press has already emerged. He was John H. Sengstacke, an immensely powerful but almost reclusive man who led The Chicago Defender for nearly 60 years, until his death last summer. For all of his power and exploits, the public record suggests that he barely existed. But Sengstacke was not just a publisher; he was a national power center.

Few know of the charges of sedition levelled againt the black press in wartime.

( 25 November 1912, Savannah, Ga.– ). John H. Sengstacke, publisher of the Chicago Defender and founder of the Negro Newspaper Publishers’ Association ( NNPA), helped save the black press from being shut down for seditious libel during World War II. He joined the staff of the Defender in 1934 as the assistant to its founder and his uncle, Robert S. Abbott. Shortly before the United States’ entrance into the Second World War, he succeeded his uncle as publisher and editor.

Throughout the war period, the Defender, like other African-American publications, criticized the treatment of black servicemen and advocated the integration of the armed forces. When the federal government considered indicting black publishers for sedition in order to silence the black press, Sengstacke worked out a compromise with the Justice Department. According to the deal, black newspapers would tone down their criticism and be more cooperative with the war effort if black journalists were given access to government officials. Sengstacke, as president of the NNPA, also helped gain accreditation for Harry S. McAlpin, the first black White House correspondent.

McAlpin’s career didn’t end when he stopped covering the news.

McAlpin was practicing law in Louisville, Kentucky where he previously had been chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In April he was one of the two leaders who were spearheading a protest against the board of aldermen in Louisville who voted down an ordinance that would have opened more neighborhoods to African-American citizens. McAlpin issued a statement that advocated boycotting of Louisville businesses in protest of what he called an “insult to Negro intelligence.”

By 1968 he had returned to Washington, D.C. to work as a hearing officer for the Social Security Administration. Later he was in the news again for being named the “first Negro hearing examiner for the Agricultural Department.” The date was October 10, 1971; McAlpin was 65 at the time.

Later he returned to his law practice in Louisville.

(From the Encyclopedia of African-American Civil Rights:From Emancipation to the Present. Charles D. Lowery – Editor, John F. Marszalek – Editor. Page 472)

McAlpin was interviewed by Edward R. Murrow, for his radio program “This I Believe” in the 1950’s.

I had a father who regrettably died when I was fifteen years old and a senior in high school. He was a man of great principle. He abhorred injustice. He believed, in spite of the handicaps he suffered because of his color, that all men were created equal in the sight of God, and that included him and me. He instilled me with his beliefs. To live by these beliefs, I have found it necessary to develop patience, to build courage, to pray for wisdom. But despite my fervent prayers, I find it is not always easy to live up to my creed.The complexities of modern-day living-particularly as I must face them day to day as a Negro in America-often put my creed to test. It takes a great deal of patience to accept the customs of some sections and communities, to try to fit into the crossword puzzle of living the illogic of a practice that will permit me to ride on the public buses without segregation and seating, but deny me the right to rent a private room to myself in a hotel; or the illogic of a practice which will accept me as a chauffeur for the rich who can afford it, but deny me the opportunity of driving one of the public buses I may ride indiscriminately; or the illogic of a practice which will accept me and require me to fight on the same battlefield but deny me the right to ride in the same coach on a train.

It takes a great deal of courage to put principles of right and justice ahead of economic welfare and well-being, to stand up and challenge established and accepted practices, which amount to arbitrary exercise of power by petty politicians in office or by the police. Trying to live up to my beliefs often has subjected me to both praise and criticism. How wise I have been in my choices may be known only to God. I firmly believe, however, that as an American, as a man, and as a Christian, I have been strengthened, and life about me has been made better, by the steel hardening fires through which my creed and my faith have carried me.

I shall continue to pray, therefore, a prayer I learned in the distant past, which I now count as my own: “God, give me serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

The first black woman to become a white house correspondent was Alice Allison Dunnigan.

Dunnigan reported on Congressional hearings where blacks were referred to as “niggers,” was barred from covering a speech by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in a whites-only theater, and was not allowed to sit with the press to cover Senator Robert A. Taft’s funeral – she covered the event from a seat in the servant’s section. Dunnigan was known for her straight-shooting reporting style. Politicians routinely avoided answering her difficult questions, which often involved race issues.

…

During her years covering the White House, Dunnigan suffered many of the racial indignities of the time, but also earned a reputation as a hard-hitting reporter. She was barred from entering certain establishments to cover President Eisenhower, and had to sit with the servants to cover Senator Taft’s funeral. When she attended formal White House functions, she was mistaken for the wife of a visiting dignitary; no one could imagine a black woman attending such an event on her own. During Eisenhower’s two administrations, the president resorted first to not calling on her and later to asking for her questions beforehand because she was known to ask such difficult questions, often about race. No other member of the press corps was required to submit their questions before a press conference, and Dunnigan refused. When Kennedy took office, he welcomed Dunnigan’s tough questions and answered them frankly.

Her autobiography, “A Black woman’s experience: From schoolhouse to White House” is not readily available to purchase.

For more of this history, suggest you see if your library has “A History of the Black Press“, by Armistead Scott Pride, and Clint C. Wilson

In this work, Dr. Wilson chronicles the development of black newspapers in New York City and draws parallels to the development of presses in Washington, D.C., and in 46 of the 50 United States. He describes the involvement of the press with civil rights and the interaction of black and nonblack columnists who contributed to black- and white-owned newspapers.

We tend to take seeing black faces in traditional news media positions of visibility for granted these days. I won’t forget people like Max Robinson , who broke the color barrier on prime time news in 1978 , or Bernard Shaw who anchored at CNN starting in 1980.

Bob Herbert, became the first black op-ed columnist at the New York Times, in June of 1993.

Nowadays we have other options. We are here in the blogosphere and very vocal on twitter.

Black voices will be heard.

Cross-posted from Black Kos

6 comments