A profile of a commercial photographer … whose capturing of the end of the steam train era in the 1950’s made him an icon (and not just to rail buffs) after the jump ….

Though he trained as a civil engineer, and made a living as a publicity/advertising photographer: people today know O. Winston Link as someone who captured (principally in nighttime, black-and-white photography) the end of the steam engine era. That it was not done on a commercial assignment – but instead as a labor-of-love – led many rail buffs to look at him as the father of amateur railroad photography (at least in the US). In addition, he also made sound recordings of that (now lost) era that only adds to his legacy. Sadly, his second wife was twice convicted of trying to sell his images (unbeknownst to him) – yet a museum in Roanoke, Virginia that bears his name is believed to be the only known museum dedicated to the work of a single photographer. Let’s have a look at his life (as well as some of his images) in order to set the record straight.

Ogle Winston Link was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1914 – named after two forebears who served in the US House of Representatives (Alexander Ogle and John Winston Jones) in the 1800’s. His father taught woodworking in the NYC public schools and encouraged his three kids in arts & crafts, which include photography.

Link became so enamored of the camera: he built his own photo enlarger while in high school. He graduated with a degree in civil engineering from the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, while serving as the photo editor for the student newspaper. His big break came while giving an address at the newspaper’s annual banquet – impressing an executive from the pioneering Carl Byoir public relations firm enough to offer him a job as a photographer in 1937.

During his five years there, he developed a style of boldness, yet being able to make a posed photograph seem authentic. He wanted to enlist after Pearl Harbor, but was classified 4-F (due to hearing loss that had been caused by having the mumps). He then left the Byoir agency to join a Columbia University war-time project: enabling aircraft to detect submarines. He was hired as both a project manager (due to his engineering degree) and as a photographer, becoming his primary focus to present to the US government.

Although he was offered his job back at the Byoir agency (after the war, when the war project closed) he felt it was time to open his own photography studio in 1946 – serving clients such as Goodrich, Alcoa and Texaco.

And it was on his way to a January, 1955 industrial photo shoot (for air conditioners) in Staunton, Virginia that he happened upon the nearby Norfolk & Western (N&W) railway. This was the last major (Class 1) railroad that had not yet switched from steam locomotives to diesel, and he enjoyed taking some photos for his personal collection … and it might have ended there.

But when N&W announced four months later that it, too, would convert … Link felt an opportunity to capture the end-of-an-era in American railroads. Emphasizing that he was not seeking a salary, he prevailed upon the N&W’s president Robert Smith to afford him access to the railroad’s employees, which they did. Making twenty trips to the Virginias over the next several years, Link took both photographs and sound recordings in what the NY Times later described as a “One-man StoryCorps”.

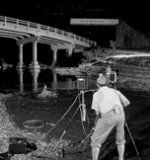

I am not an equipment expert – this is where our friend Eddie C would shine – but railroad personnel became used to seeing Link and his assistants carry his Rolleiflex camera and numerous Sylvania Blue Dot lighting equipment. The latter was especially necessary as Link wanted to do the bulk of his moving train shots at night – “I can’t move the sun – it is always in the wrong place – and I can’t even move the tracks”. He did, however, make some color photos as well, which is not always known to rail buffs. And all of this on his own time, while his ‘day job’ was still that of advertising photography. In addition, he photographed the construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in his native NYC.

Here are a few of his celebrated rail photographs:

From Hawksbill Creek, Virginia –

At a drive-in theater in Iaeger, West Virginia – Winston Link paid the couple to sit in Link’s convertible for $10 (in 1956). The first is the actual photo he took (for which the lighting drowned-out the screen’s image). The second was the actual released photo (after adding the plane from a negative he took).

View of the last steam train (taken in Max Meadows, Virginia in 1958).

Taken in Stanley, Virginia in 1956.

A train passing outside a living room in Lithia, Virginia – note the kitteh on the rug keeping an eye on the sleeping dog.

Crossing the New River in Radford, Virginia in 1957.

And to show a color photograph (after the conversion to diesel) at Shaffers Crossing in Roanoke, Virginia in 1960.

His work appeared in Trains magazine, and his sound recordings on albums (from 1957-1977) of steam railroad sounds. He retired at age 69 in 1983, and a touring exhibition of his work that same year made him more well-known to the general public.

In his early 80’s, his second marriage was now becoming toxic. Claiming that Link was now suffering dementia (and that she had power of attorney) his wife was eventually convicted of attempting to sell some of his works for her own gain. After her release six years later (and after Link’s death) she attempted to sell some of his works again – this time on eBay – and received a three-year sentence.

One final aspect of this marriage (in dispute) was whether Link was preyed upon by an adulterous wife (or, via her account) whether she was driven to it by his own vengeful behavior? The matter is explored in a documentary film from a few years ago. He himself had a cameo role in a film, appearing in October Sky in 1999 as … what else? … a railroad engineer.

O. Winston Link died in January, 2001 of a heart attack at the age of 86, driving himself to a hospital … to no avail, dying outside … where else? … a train station in South Salem, New York.

Many of his rail photos (as well as an accompanying audio CD of his sound recordings) are available in the book Life Along the Line, which also tells his life story. A more complete CD allows one to hear the sounds of steam trains rolling through small towns in the Virginias.

Link was involved in the planning of the museum that bears his name – which opened three years after his death at a former N&W station house in Roanoke, Virginia. Original prints can sell to collectors for thousands of dollars, while his images can be purchased (for much less) on postcards, calendars and the like.

For someone born in New York City, small-town America appealed to O. Winston Link – and a NY Times writer opined that he captured not only the end of a semi- prosperous Appalachia … but the end of an idealized small-town America. He once remarked that – unlike Ansel Adams, whose landscape photos would look the same way into the future – he had captured an era that would soon no longer be. Yet he never considered himself an artist, saying “I know what I want and I know how it’s going to get done and I know what it’s going to look like when I’m finished.”

Let’s close with two songs about railroading … one is an actual N&W corporate song (the railroad was merged into the Norfolk Southern Railway in 1982).

The other is a blues classic about a different rail line – the Louisville & Nashville Railroad (L&N) which eventually became part of CSX in 1982. The music to Riding on the L&N was composed by Lionel Hampton (with Dan Burley writing the lyrics). And below you can hear a 1966 version by bluesmen John Mayall and Paul Butterfield.

Around the bend came the L&N

Loaded down with a lot of men

One jumped off and threw the switch

Nobody knew just which-was-whichA man named Mose with a great big nose

Was sleeping on a pile of clothes

The conductor came and rang the bell

The porter hollered, “Well, well, well!”A man named Quinn caught the L&N

Heading around old horseshoe bend

The train slowed down and Quinn jumped off

He wasn’t dead ’cause I heard him call:“I’m riding, riding on the L&N

I ain’t jiving …. Riding on the L&N”

2 comments