A look at two men named Jim Marshall (from different sides of the Atlantic) who influenced the world of rock musicians – one made its equipment, the other photographed it – after the jump …

Jim Marshall was a good photographer … who became a legendary one because of what he captured for people. On album covers of the 1960’s and 70’s, I saw numerous excellent musicians pictured with Photo by Jim Marshall as the caption. There were both obviously posed photos, as well as numerous “down-time” photos that showed their non-stage persona. Like his English namesake, this Jim Marshall was in the right place at the right time: allowed unlimited access in those more freewheeling days, yet Jim Marshall also engendered a sense of trust with his subjects.

He was born in Chicago in 1936, with his family eventually relocating to the Bay Area. He became an avid photographer in high school before serving in Air Force. Known to have at least one Leica camera with him at all times, he relocated to New York after military service and was hired as a staff photographer by both Columbia and Atlantic Records in the early 1960’s. This was the career break to-end-all, and over time his photos graced more than 500 album covers.

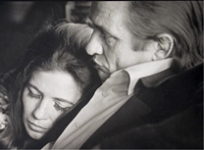

Besides rock and roll, he often photographed other artists that performed in the San Francisco Bay Area (when he relocated back there later in the 1960’s). These included the comic Lenny Bruce, to country music star Johnny Cash … yes, it was Jim Marshall who took this legendary image backstage at San Quentin, when Jim Marshall said, “John, let’s do a shot for the warden”.

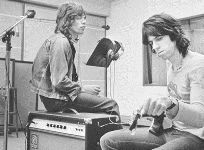

In addition to his live concert shots and posed portraits … as noted, he engendered such trust that his photos also included downtime photos such as these.

And for many years, he captured images of the jazz stars who passed through the city’s clubs (such as the Black Hawk and Keystone Korner) from John Coltrane to Miles Davis (L-to-R).

In the introduction to his 1997 retrospective book Not Fade Away, Jim wrote:

When I’m photographing people, I don’t like to give any direction. There are no hair people fussing around, no makeup artists. I’m like a reporter, only with a camera; I react to my subject in their environment, and if it’s going well, I get so immersed in it that I become one-with-the-camera.

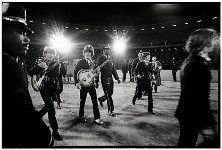

Another break occurred when Rolling Stone was founded in San Francisco in 1967 – and their use of his photographs enabled him to cultivate bonds with rock musicians (as the magazine was considered quite a counter-cultural publication back then). In addition, he was the only photographer allowed backstage at the last Beatles concert in San Francisco in 1966, and being based in that city with the musical acts passing through Bill Graham’s Fillmore venues (plus the Monterey Pop Festival) meant that he saw everyone.

He was designated the chief photographer at the 1969 Woodstock Festival, and I recall visiting a New York art gallery in 1981 that showed just a few of his concert photos: one could almost hear the sound coming out of them. He was, if you will, the Annie Leibovitz of his day: having the sort of backstage access that only someone like Annie could command in today’s “Have your people talk to my people” days. Indeed, Annie herself called him “the rock ‘n’ roll photographer.”

Jim Marshall died five years ago this month – as mentioned, he was featured (in miniature) in my first Top Comments diary five years ago yesterday – in New York City at the age of 74.

His rock photos are captured in Not Fade Away as previously noted, but also in several other books of photography. And just last year, Marshall’s photography appeared in the new book The Haight: Love, Rock, and Revolution written by Joel Selvin.

Also just last year, the Grammy foundation awarded him the first Trustees Award ever given to a photographer. Tributes were made by his peer (Henry Diltz) and this by Graham Nash:

The world is a better place because of the talent and vision of my friend Jim Marshall. He, of course, took countless iconic photographs over the years and always brought a deeper insight into the world of photography and music. His images can be likened to haiku poetry: everything in its proper place … no “extra” information … only the very essences necessary to convey what he wants us to see. Never one to be dissuaded from a good shot, he opened our eyes to the wonders of his portraits. Jim’s images always have a sense of completeness and his ability to compose instantly is renowned. It’s possible that I took the last portrait of Jim shortly before his untimely passing. Jim may be gone but his images will absolutely stand the test of time and be around for us to see and enjoy for years to come.

—————————————————————————————————

The other focus of this essay is also named Jim Marshall – a man who began life a sickly young boy, became a jazz drummer, found work as an electrical engineer for a day job, then became a drum teacher, next opening a drum shop, later selling guitars … and finally branching into guitar amplifiers, which made his last name famous around the world. Famous enough, in fact, to be recognized by Queen Elizabeth.

Known as the Father of Loud, he is considered by rock guitarists to be among the Four Forefathers of the modern electric guitar sound. The other three? Leo Fender (of electric guitar, bass and amplifier fame), Les Paul (with his signature guitars for Gibson) and the least well-known of the group, Seth Lover – who created the hum-cancelling electric guitar pick-ups – the rectangular devices on the body of an electric guitar (under the strings) that convert sound to electrical impulses (which the amplifier later converts back to sound) – known as humbucking pick-ups, when he worked for Gibson Guitars. Together, those four individuals (and others) shaped rock and roll.

James Charles Marshall was born in West London in July, 1923 and as a child was diagnosed with tubercular bones – spending years in the hospital cocooned in a plaster cast. Mercifully he outgrew the disease by his teens, but this condition exempted him (as a seventeen year-old) from World War II and during the war years he began as a band singer.

As an electrical engineer, he built a portable PA system (so his vocals could be heard) and then – when the drummer was drafted into the war effort in 1942 – Jim became a drummer, as well. He hitched a trailer to his bicycle, carrying his drums and PA system behind him (due to war-time rationing of automobile fuel).

After the war, he took drum lessons (hoping to emulate his idol Gene Krupa) and in the 50’s became a touring drummer.

Then, he became a drum teacher himself later that decade, with a few students who later made their mark on British rock music. These included Mick Underwood (with Ritchie Blackmore, Ian Gillan and Peter Frampton), Micky Waller (with Rod Stewart and Jeff Beck) and especially Mitch Mitchell (from the Jimi Hendrix Experience).

All of these earnings helped him open a drum shop in the west of London in 1960. As the folk music (and later rock music) boom came – plus, the fact that drummers brought their bandmates with them – he added guitars and amplifiers to his inventory and soon he began to have customers who would later leave their own mark on the music world: Ritchie Blackmore (later of Deep Purple) and Pete Townshend (later of The Who).

In time, they convinced Marshall there was a market for amplifiers that were (a) less expensive than the imported American models, (b) having a more raw (and less ‘clean’) rocking sound, and (c) were more powerful and louder, as well. With his electrical engineering background, Jim Marshall set-out to fulfill his customer’s needs: hiring an 18 year-old EMI music electronics apprentice named Dudley Craven at the suggestion of Jim Marshall’s shop repairman … and then founding Marshall Electronics in 1962.

It took five tries before Craven (and the rest of the team) created a model that gave the type of sound that Britain’s young guitarists wanted ….. but when they did, it created a sound that – while Marshall amps are not exactly known for their wide range of sounds – have been popular for over fifty years.

Today on concert stages around the world, you will see a Marshall head (the smaller, electronics/tube component) sitting on top of a (Celestion) speaker cabinet … and often two stacked-together, with the top cabinet angled (with a young Eric Clapton shown above). Originally, Jim Marshall did the top cabinet angle only for stylistic reasons – but discovered later that the top two speakers face upwards slightly, thus allowing higher frequencies to cut through over a distance.

Musicians have been known to have placed multiple stacks on-stage …. for which some are empty (to create an effect). And in the 1984 cult film This is Spinal Tap – a Marshall amp is shown to have a volume control which (like most manufacturers) goes from 0 – 10 … but in this film, it goes … to “11”.

Jim Marshall went on to receive much recognition for his creation: winning a 1984 Queen’s Award for Export, asked to contribute his handprints in 1985 to the Rock & Roll Walk of Fame and in 2003 received a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth, for his services to the music industry … and charity.

And the charity portion was due to the fact that Jim Marshall never forgot the treatment he had received for TB in his youth, donating a great deal of money to his old hospital in particular and medical charities as well.

Jim Marshall died in April, 2012 at the age of 88. Tributes came in from around the world of rock, there is a 2003 biography entitled Jim Marshall: The Father of Loud and a theater is named after him in his adopted hometown of Milton Keynes, England.

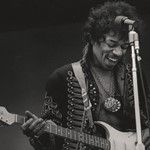

For a music choice: there is no better person than yet-another Jim Marshall. Well, to be precise: one James Marshall Hendrix. Jimi Hendrix came to England in mid-1966, and was looking for a set-up that worked with his enormous sound. Unsurprisingly, he fell in love with the sound of Jim Marshall’s amplifiers and asked his drummer Mitch Mitchell to introduce him.

Knowing that Mitch knew me, Jimi said to him, “I’ve just got to have this Marshall stuff because it sounds so good. I also wouldn’t mind meeting up with this character who has got my name-James Marshall.”

I must admit, when Mitch introduced me to Jimi, I immediately thought, “Christ, here we go again-another American wanting something for nothing.” Thankfully, I was dead wrong. The very first thing Jimi said to me was, “I’ve got to use your stuff, but I don’t want anything given to me. I want to pay the full asking price.” That impressed me greatly, but then he added, “I am going to need service wherever I am in the world, though.” My initial reaction was, “Blimey, he’s going to expect me to put an engineer on a plane every time a valve (tube) needs replacing. It’s going to cost me a bloody fortune!”

Instead, I suggested our staff teach Hendrix’s tech, Gerry Stickells, basic amp-servicing skills, such as changing and biaising the valves. He must have been a very good learner, because we were never called on to sort out any problems.

And for the rest of his (short) career, one always saw Jimi photographed in front of a Marshall stack. That’s because the photographer Jim Marshall often photographed him – and especially at Jimi’s triumphant return to the US at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 (as well as at Woodstock, two years later).

One of the songs Jimi played at Monterey was from his landmark debut album Are You Experienced – a more subdued tune called The Wind Cries Mary where I first heard how versatile his sound was; not limited to high-decibels. And below you can hear it.

After all the jacks are in their boxes

And the clowns have all gone to bed

You can hear happiness staggering on down the street

Footprints dressed in red

And the wind whispers, “Mary”A broom is drearily sweeping

Up the broken pieces of yesterday’s life

Somewhere, a queen is weeping

Somewhere, a king has no wife

And the wind, it cries, “Mary”The traffic lights, they turn blue tomorrow

And shine their emptiness down on my bed

The tiny island sags downstream

‘Cause the life it lived is dead

And the wind screams, “Mary”Will the wind ever remember

The names it has blown in the past?

And with its crutch, its old age and its wisdom

It whispers, “No, this will be … the last”

And the wind cries, “Mary”

3 comments