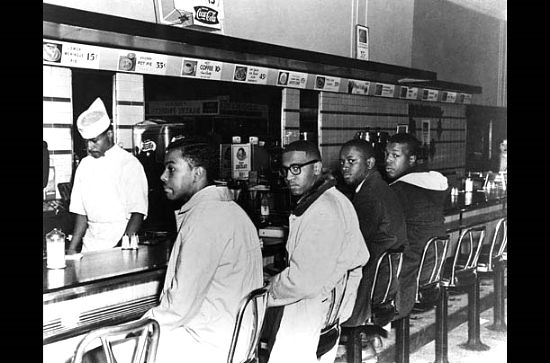

This section of the lunch counter from the Greensboro, North Carolina Woolworth’s which is now preserved in the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History has a living story to tell.

Many of you were not even born in 1960 when those seats were occupied by four very brave young black college students, Ezell Blair, Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil and David Richmond, who risked their lives to demand their right to be served, and who sparked a massive wave of sit-ins and boycotts against racial segregation – led by other young people.

I remember my parents, and my friends in junior high school deciding to boycott Woolworths as we watched images of jeering, pushing, spitting, punching, epithet yelling white people, trying to stop progress. I also remember watching a few brave young white students take similar abuse for deciding to join the black student protestors.

The Civil Rights Movement Veterans (CRMVet) website gives the background to the story:

Sit-Ins Background & Context

1960 was the year of the student-led lunch-counter sit-ins. For those who are not familiar with lunch-counters, they were the fast-food providers of the era (McDonalds, Taco Bell, Burger King, and others were just getting started). Suburban malls were still few and far between, and “downtown” was the main shopping district. Most large stores had lunch counters where a cup of coffee cost a dime, and you could get a cheeseburger, fries, and Coke for 60 cents. Lunch-counters provided quick cheap meals for shoppers, students, and workers on break the same way that shopping-mall food-courts do today. Nationally, there were more than 30,000 lunch counters in drug and department stores, bus terminals, and public buildings. Many were part of large national chains such as Woolworth (2,130 stores), McCrory (1,307), and Kress (272).

In most segregated communities, Blacks were encouraged to shop at chain and department stores, but they were not permitted to eat at a store’s “white-only” lunch counters and restaurants. And unlike whites, Blacks were not permitted to try on clothes prior to buying them or return purchases that did not fit. The sit-ins focused on the lunch-counters and restaurants, but all forms of discrimination were the ultimate target. In most cases where the sit-ins achieved victory, agreements to desegregate lunch-counters usually included eliminating the other forms of consumer discrimination. Note that in most southern communities, segregation was not a matter of personal choice on the part of white business owners. Segregation was mandated by law (see examples). Blacks who tried to use “white-only” facilities could be, and often were, arrested for violating a segregation ordinance (and in theory a white establishment could be held liable for serving Blacks).

But after Federal courts began declaring school and bus segregation laws unconstitutional, most southern prosecutors were careful to charge Blacks who defied segregation with general crimes such as “Disturbing the Peace” or “Disorderly Conduct” rather than violation of race-specific segregation laws. In this way they prevented the courts from overturning the segregation ordinances on appeal, and that allowed store owners to continue claiming that they had to deny service to Blacks because “it’s the law.” This cynical ploy was used to maintain segregation until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 eliminated all segregation laws.

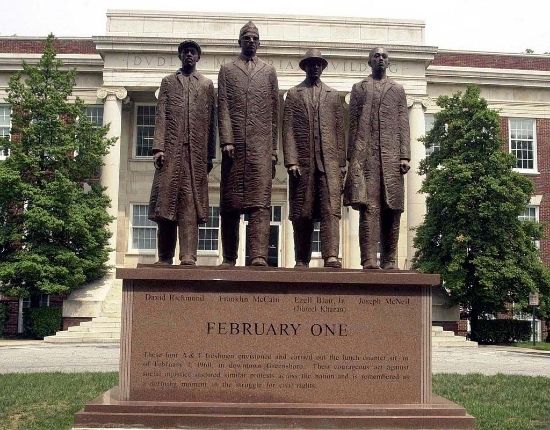

We learn the names of “leaders” but rarely remember all those people, mostly young, who stepped up and fought back. North Carolina A&T’s campus has not forgotten.

February One (also referred to as the A&T Four Monument) is the name of the 2002 monument dedicated to Ezell Blair, Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil and David Richmond who were collectively known as the Greensboro Four. The 15-foot bronze and marble monument is located on the western edge of the campus of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro, North Carolina. James Barnhill, the sculptor who created the monument, was inspired by the historic 1960 image of the four college aged men leaving the downtown Greensboro Woolworth store after holding a sit-in protest of the company’s policy of segregating its lunch counters.

CRMVet gives more detail on what happened and how the first sit-in sparked a movement:

On February 1, 1960, four Black men from NCA&T – Ezell Blair Jr, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond – sit down at Woolworth’s “whites only” lunch counter and ask to be served coffee and doughnuts. They are refused. Though they are prepared to be arrested that does not occur. They stay until the store closes. The next day they return, now joined by Billy Smith, Clarence Henderson, and others. They sit from 11am to 3pm but again are not served. While they wait, they study and do their school work. The local newspaper and TV station cover this second sit-in. At first they call it a “Sit Down,” but soon everyone is using the term “Sit-In.” Blair tells an interviewer: “Negro adults have been complacent and fearful … It is time for someone to wake up and change the situation … and we decided to start here.”

The Greensboro students activate the telephone networks that had been built over the preceding months, and word is flashed across the South – from one Black campus to the next – Sit-In! Greensboro, North Carolina! Suddenly everyone is aware that Black students have openly defied a century of segregation. Greensboro students form the Student Executive Committee for Justice to sustain and expand the campaign. The Greensboro NAACP endorses their action. On February 3rd, more than 60 students, now including women from Bennett who have returned from break and students from Dudley High School, occupy every seat at the Woolworth’s counter in rotating shifts for the entire day. By February 4th they number close to 300 – including white students from Womens College (now University of North Carolina) – and the sit-ins spread to Kress and Walgreens lunch counters, and then to other Greensboro restaurants. In the following days as many as 1,000 protesters demand an end to segregation in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The Ku Klux Klan reacts. Led by George Dorsett – North Carolina’s official State Chaplain – they heckle and harass the students. The students are not deterred. Hoping that their presence will deter white violence, the NCA&T football team joins the protests. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) sends organizers to help train the students in the tactics and strategies of Nonviolent Resistance. Sit-ins, picket lines, and boycotts continue off and on as negotiations get under way, the lunch counters are closed and reopened, and public opinion weighs in. The segregation laws are strengthened and dozens of students are arrested and charged with “trespass” for sitting-in. Woolworth and Kress stores in the North and West are boycotted and picketed in support of the sit-in movements that are now spreading across the upper and mid South, Atlanta, and New Orleans. When the college students leave for the summer, Dudley High students carry on. Finally, in July, the national drugstore chains agree to serve all “properly dressed and well behaved people,” regardless of race.

Two major documentary films that you should see, have been made about the sit-ins in Greensboro.

This is a trailer for the award winning feature length documentary, February One – The Story of the Greensboro Four...The world can change in a day

Despite hard-fought gains in the fight for racial equality, segregation remained firmly entrenched in 1960 America. Black citizens in the South were still treated as second-class citizens and their calls for justice remained largely unheard by the nation. There had been some advances in the arena of civil rights with the Brown v. the Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision (1954), the Montgomery bus boycott (1955-1956) and the federally enforced desegregation of Little Rock (Ark.) High school (1957), but after that, strong defiance by ardent segregationists pushed the Movement into retreat.

February 1, 1960 changed all that.

Based largely on first hand accounts and rare archival footage, the new documentary film February One documents one volatile winter in Greensboro that not only challenged public accommodation customs and laws in North Carolina, but served as a blueprint for the wave of non-violent civil rights protests that swept across the South and the nation throughout the 1960’s.

The second one, Seizing Justice, is available online at the Smithsonian Channel, and on YouTube.

In February of 1960, a simple coffee order at America’s favorite five-and-dime store sparked a series of events that would help put an end to segregation in the United States. Join us as we detail the extraordinary story of otherwise ordinary young men, four African-American college students whose nonviolent sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter started a revolution.

I’d like to also mention teacherken’s Daily Kos diary from 2011, It was a simple action.

I hear criticisms leveled too often at young people. The history of youth activism is directly connected to the movements taking place today…no longer using telephone networks, like those black student’s from the 60’s, but today’s media of facebook and twitter to get young folks organizing, protesting and out into the streets.

We need to both honor those who stood up in the past, but also to join and support what is going on right now.

The struggle continues.

Cross-posted from Black Kos.

13 comments