As we all turn our eyes towards the epic tragedy unfolding in Haiti, and as massive relief efforts continue, I am enraged by right-wing commentary that encourages our citizenry to turn their backs on Haiti and Haitians. For what do they have to do with us?

The history of Haiti, and its relationship to the United States is as old as the American Revolution; not withstanding the spews of bigots. This monument stands in Savannah Georgia as silent testimony to our shared history.

In October, of 2007 years of effort by of members of the Haitian American Historical Society, Haitian-Americans and members of the Savannah community bore fruit.

Little notice was paid in the national media, but the Haitian Ambassador attended the event and AP did cover the story.

In the American State of Georgia, Finally a Tribute to Haitian Soldiers for Heroism in American Revolution

By RUSS BYNUM, Associated Press Writer

SAVANNAH, Ga. – After 228 years as largely unsung contributors to American independence, Haitian soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War’s bloody siege of Savannah had a monument dedicated in their honor Monday. About 150 people, many of them Haitian-Americans who came to Savannah for the event, gathered in Franklin Square where life-size bronze statues of four soldiers now stand atop a granite pillar 6 feet tall and 16 feet in diameter.

“This is a testimony to tell people we Haitians didn’t come from the boat,” said Daniel Fils-Aime, chairman of the Miami-based Haitian American Historical Society. “We were here in 1779 to help America win independence. That recognition is overdue.”

In October 1779, a force of more than 500 Haitian free blacks joined American colonists and French troops in an unsuccessful push to drive the British from Savannah in coastal Georgia. More than 300 allied soldiers were gunned down charging British fortifications Oct. 9, making the siege the second-most lopsided British victory of the war after Bunker Hill. Though not well known in the U.S., Haiti’s role in the American Revolution is a point of national pride for Haitians. After returning home from the war, Haitian veterans soon led their own rebellion that won Haiti’s independence from France in 1804.

A Boston Haitian-American newsletter covered the genesis of the statue and its history in depth.

“It’s a huge deal,” said Philippe Armand, vice president of the Association of American Chambers of Commerce in Latin America, who flew to Savannah from the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince. “All the Haitians who have gone to school know about it from the history books.” Fils-Aime’s group has Monument dedicated to Haitian soldiers in Savannah spent the past seven years lobbying Savannah leaders to support the monument, which the city approved in 2005, and raising more than $400,000 in private donations to pay for it. Fils-Aime said the historical society still needs $250,000 to finish two additional soldier statues. As it stands now, the monument features statues of two Haitian troops with rifles raised on either side of a fellow soldier who has fallen with a bullet wound to his chest. The fourth statue, a drummer boy, depicts a young Henri Christophe, who served in Savannah as an adolescent and went on to become Haiti’s first president – and ultimately king – after it won independence.

The young drummer boy, who would go on to be a founder of a free Haiti, Henri Christophe, could have shed his blood and died here, but inspired by revolutionary zeal her returned home to Haiti to free his brethren.

Henri Christophe

Historians still debate Christophe’s later role in Haiti’s history, as President and then King, but the fact remains that he fought here.

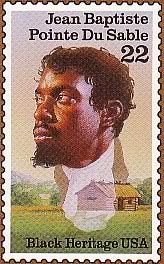

How quickly we forget another Revolutionary War Era contributor to our history. I speak of Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable, who is immortalized on one of our postage stamps.

DuSable, honored as the founder of Chicago, represents not only Haiti, and our deep connections, but ties to our First Nations peoples as well.

Du Sable’s birth year is highly uncertain, but is generally believed to have been between 1730 and 1745. Many of the stories about him are unconfirmed, especially those involving his early years. He was born at Saint-Marc in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue, present-day Haiti, to a slave named Suzanna and a French pirate’s mate named Pointe du Sable who served on the Black Sea Gull. Suzanna may have been killed in a Spanish raid on Saint-Domingue. If this raid took place, Jean Baptiste may have escaped by swimming out to his father’s ship. After his father sent him to study at a Catholic school in France, du Sable and a friend, Jacques Clamorgan, traveled to Louisiana and then to Michigan, where he married a Potawatomi woman named Kittahawa (fleet-of-foot). To marry her, the twenty-five-year-old Jean Baptiste had to become a member of her tribe. He took an eagle as his tribal symbol. The Potawatomi called him “Black Chief,” and he became a high ranking member of the tribe. They had a son and daughter, Jean and Susanne.

In 1779, during the Revolutionary War, he was imprisoned briefly by the British in Fort Michilimackinac in Michigan, because of his French connections and on suspicion of being a US spy. He helped George Rogers Clark in his capture of Vincennes during the war. From the summer of 1780 until May of 1784, du Sable managed the Pinery, a huge tract of woodlands claimed by British Lt. Patrick Sinclair on the St. Clair River in eastern Michigan. Du Sable and his family lived at a cabin at the mouth of the Pine River in what is now the city of St. Clair.Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable first arrived on the western shores of Lake Michigan about 1779, where he built the first permanent nonindigenous settlement, at the mouth of the river just east of the present Michigan Avenue Bridge on the north bank. Before it was anything else, Chicago was a trading post. As its first permanent resident, du Sable operated the first fur-trading post during the two decades before his departure in 1800. Du Sable built his first house in the 1770s on the land now known as Pioneer Court, thirty years before Fort Dearborn was established on the banks of the Chicago River.

Why do I say we turned our backs on Haiti? Because we did. We were not alone in this, and the pages of history illuminate many of the answers to questions often raised about “why is Haiti so poor?”

The Guardian had an incisive piece written around the time of the overthrow of Aristide:

From the outset Haiti inherited the wrath of the colonial powers, which knew what a disastrous example a Haitian success story would be. In the words of Napoleon Bonaparte: “The freedom of the negroes, if recognised in St Domingue [as Haiti was then known] and legalised by France, would at all times be a rallying point for freedom-seekers of the New World.” He sent 22,000 soldiers to recapture the “Pearl of the Antilles”.

France, backed by the US, later ordered Haiti to pay 150m francs in gold as reparations to compensate former plantation and slave owners as well as for the costs of the war in return for international recognition. At today’s prices that would amount to $18bn. By the end of the 19th century, 80% of Haiti’s national budget was going to pay off the loan and its interest, and the country was locked into the role of a debtor nation – where it remains today.

They go on to detail not only the depredations of rule under the brutal Duvalier’s, father and son, but the role of the global arbiters in determining Haiti’s fate:

Any prospect of planting a stable political culture foundered on the barren soil of economic impoverishment, military siege and international isolation (for the first 58 years the US refused even to recognise Haiti’s existence). In 1915, fearing that internal strife would compromise its interests, the US invaded, and remained until 1934. If those who now preach compromise had practised those values in the past, Haiti might have nurtured the kind of political traditions that could withstand its divisions today. Haiti is a reminder of how Western democracies have wilfully amassed their wealth on the backs of impoverished dictatorships.

So Haiti lurched from coup to coup, most notably under the dictatorship of “Papa Doc” Duvalier and then his son, “Baby Doc”, supported by the US and France. In 1990 Aristide appeared as the best hope to break the cycle. With an overwhelming democratic mandate, the liberation theologian was swept to power, as Haitians brushed the floor ahead of him with palm leaves. Deposed in a coup, he returned in 1994 with US military assistance. But, in return for political freedom, Aristide was compelled to accept economic enslavement at the hands of the IMF and the World Bank. Post-colonial military aggression gave way to brutal globalisation. Before Aristide had even considered fixing the elections, the West had already rigged the markets. Take rice. Forced by the agreement to lower its import tariffs, Haiti found itself flooded with subsidised rice from the US, which drove Haitian rice growers out of business and forced the country to import a product that it once produced. When the country fined US rice merchants $1.4m for allegedly evading customs duties, the US responded by withholding $30m in aid.

Dr. Eric Pierre, from the Ontario Historical Society wrote this eloquent piece, on bicentenary of the independence of Haiti, in 2004. He spoke first of the history of enslavement and resistance

The most significant and coordinated assault on slavery and the colonial system started in 1791, two years after the French revolution. The French Revolution did create a historical context favorable to the events that culminated with the final victory of 1804. But it did not inspire the thirst for freedom nor did it create the determination, courage, strategic discipline and military intelligence of the African masses. The spirit of rebellion revealed itself in the uprisings taking place on the slave boats during the trips from Africa to the Americas and the Caribbean. It manifested itself very early with such brave acts as escapes, poisonings, fires, suicides, and infanticides.Women preferred to undergo abortions or even kill their own children instead of bringing them into a world of humiliation and infamy. It is important to underscore the significant contribution of women in these early stages. We should also recognize the injustice dealt to them by history for failing to pay homage to the specific identity of those female freedom fighters who were imprisoned, hanged and tortured. They will remain illustrious anonymous forever. The rebellion evolved into more organized expressions such as “maronnage” and unsuccessful uprisings such as the one led by Mackandal.

He then spoke of the betrayals, even from those like Simon Bolivar, who was given Haitian assistance to launch revolutions in Latin America:

The colonial powers quickly realized the significance of our independence. They viewed it as a dangerous precedent and vowed to keep the liberation disease from spreading. They quarantined the new nation. Cardinal Talleyrand called Haiti a “haven of barbarian piracy” until France granted conditional recognition to the independence in 1825 upon payment of the first installment of an indemnity of 100 million francs. It took the United States approximately 60 years to recognize Haiti’s independence when in December 1861 President Lincoln said that he “failed to discern.. any good reason not to recognize” the independence of Haiti. The Vatican did not have any diplomatic relations with the new nation until 1860. In the meantime the Catholic religious guidance of Haitians was left to a combination of real priests, excommunicated priests or impostors. No foreign heads of state set foot on Haitian territory for any extended visit before President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934, at the end of the American occupation.

Haiti was indeed a leading force in the struggle for freedom in the Americas. The Venezuelan revolutionaries Francisco Miranda and Simon Bolivar were given the necessary assistance: food, weapons, and Haitian soldiers in their struggle for independence. The same Simon Bolivar did not invite Haiti to the Congress of Panama. His representatives were given specific instructions: “The government regards with repugnance the idea of treating Haiti with the same etiquette generally maintained between civilized nations”. The tragedy of Haiti is a history of isolation, ostracism, and interventions. It is also a history of betrayal by an unscrupulous ruling class more interested in conspicuous consumption and personal wealth than nation building. At the same time, it is a history of demands for freedom, human rights, and human dignity, not only for Haitians, but also for all citizens of African descent. For that matter, it includes any social class, nation, or ethnic group whose rights are being trampled upon.

The demonization of Haiti, and Haitians continues from right wingers in our country. As a community we must recognize that the Haitian people will need our help in years ahead to rectify the past, and to forge a new future. Haitians have always had the audacity to hope, the courage to struggle, and the strength to survive, no matter what.

“Mesi” or thank you, in Kreyol.

cross posted at Daily Kos

29 comments